Place of observation: Small pond and Capital Lake

Geographic site: North America, Europe, South Africa, Asia

Anas Platyrhychnos

Introduction:

Mallard ducks are amongst the most common and abundant ducks, found in North America, Europe, and numerous other places around the world. They inhabit both fresh and salt water wetlands and migrate for the winter season before coming back to breed in Spring. The mallard is the ancestor of nearly all other domestic ducks and often interbreed with other members of the Anas genus.

Mallard ducks are amongst the most common and abundant ducks, found in North America, Europe, and numerous other places around the world. They inhabit both fresh and salt water wetlands and migrate for the winter season before coming back to breed in Spring. The mallard is the ancestor of nearly all other domestic ducks and often interbreed with other members of the Anas genus.

I chose to study mallards because although they are an animal I’ve been familiar with my entire life, I knew very little about them. I had seen them in parks, ponds, and lakes, but had no close up experience with them. I decided to change that.

Cultural History:

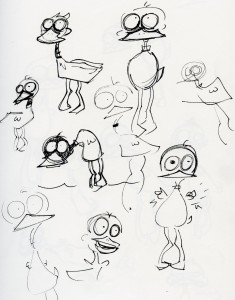

Ducks have been present in our culture for years, ranging from children’s stories, to animated cartoons, to video-games. Since the animal has been geared toward younger audiences more often than not, they have become almost a caricature of their natural state. We get used to seeing them animated and anthropomorphized. It was also very difficult to find mallards specifically throughout culture.

In early myth and Native American culture, the duck is generally described as a foolish creature. They appeared incredibly gullible and are often the victims of trickster characters. Mostly, they appeared in the background of stories and myths rather than as the main character, such as The Hell-Diver and The Spirit of Winter, where a mallard is the injured friend to the main character, The Hell-Diver (DL, Ashliman, “Folklore and Mythology”).

Similarly, ducks are used in a variety of children’s stories and fables that we still frequently come across. Perhaps the most common of them being, “The Ugly Duckling” by Hans Christian Anderson. Although mallards did not appear in the original story, they did show up in the animated film made in 1939.

Ducks certainly have never been strangers to the animated world. Some of the most recognized studios utilize duck characters; Daffy Duck and Donald Duck. Neither of these characters are really mallard specific, although Daffy does harbor a white stripe across his neck (a trait recognizable on male mallards).

Another popular duck phenomenon in our culture is that of the toy rubber duck, which was made popular by Jim Henson in the 1970’s on Sesame Street with the hit song “Rubber Duckie”. Since then these toys have been mass produced into hundreds of variations and characters, and many countries around the world even host annual rubber duck races.

A sailing duck encounters a hoard of rubber ducks in the sea.

And of course, ducks have had a place in our culture for decades as hunted waterfowl. Duck hunting, although present since prehistoric times, was re-established in the 17th century with the use of modern weaponry such as the shotgun. Since then duck hunting (and waterfowl hunting in general) has become much of an outdoor sporting event. Standard hunting season is generally through Fall and Winter with four main flyways which the birds follow, and the hunters track. Most hunters use an array of equipment for optimum hunting which include blinds, decoys, and calls (Waterfowl Hunting). Hunting is a huge past time, especially in North America, which has even been juvenilized with games such as Nintendo’s ‘Duck Hunt’ released in 1984. In this game classic, players use a toy gun to shoot ducks for points.

Natural History

Kingdom: Animalia

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

Genus: Anus

Anatidae: Animals in this family have fully webbed feet and oils in their feathers that repel water. They are very good swimmers.

Anas: These ducks are dabbling ducks (surface feeding ducks). They have defined lamellae which aid in filter-feeding when obtaining food in moody water (Merne, 94).

Average length: Male; 24.7″, Female; 23″

Average weight: Male; 2.7lbs, Female; 2.4″

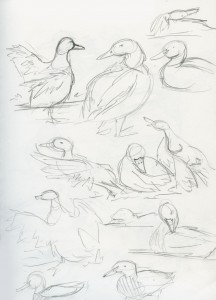

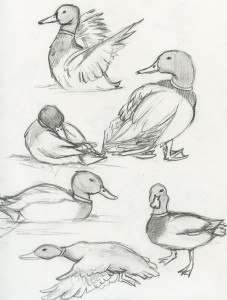

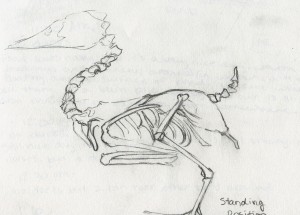

Physical: The male mallard is distinguished by it’s vibrant green head that is separated from his chestnut brown chest, with a white ring around his neck. His sides are a mixture of gray and tan feathers with black tail coverts. There is a blue speculum (specifically colored portion of the wing) which is bordered by black. He has a white underbelly, a yellow bill, and deep orange feet. The female has darker, speckled brown feathers with a similar blue speculum. Her bill is a darker shade than the male’s (Merne, 94).

Vocal: The female is the most vocal of the two, with a series of loud “quacks”, while the male makes a quieter, raspier “kreep” sound. They are typically uttered in three part intervals. There are also different types of sounds for different occasions, such an inciting call, and a “hail call” from the female which is to indicate her location to a male. The male has a grunt whistle which he makes after in taking water, and even another specific whistle after sex or rape (Miller DB).

Habitat: Mallards are abundant throughout North America, Europe, Asia, and South Africa. They stay in wetlands and nest in high grass around the water.

Diet: Dabbling ducks don’t dive to eat but linger at the surface for their food. They dip below water to eat seeds or vegetation. They consume worms, roots, insect larvae, seeds, and an array of other things they can come across. Many mallards are also accustomed to being fed by humans. (Merne, 9)

Behavior: Breeding is in the Spring and their eggs usually hatch sometime in May (on average the female will have 9 eggs). The mother guides the ducklings without the drake and within two months they usually have full feathers. In the early Summer the ducks begin to molt (shed feathers that will be replaced by new ones) and become flightless for about three weeks. Males also may begin to court female mallards, while the later part of Summer is spent preparing for migration. Then they begin to nest in grass cover near or around wetlands. Mallards are usually monogamous, but sometimes males pursue other females in forced intercourse. They have also been observed having sex with other males, and eve take part in necrophilia. (More information here). Because mallards are found in many public places, some have become very approachable to humans, though they are generally territorial to each other (“All About Birds”, Cornell University).

Behavior: Breeding is in the Spring and their eggs usually hatch sometime in May (on average the female will have 9 eggs). The mother guides the ducklings without the drake and within two months they usually have full feathers. In the early Summer the ducks begin to molt (shed feathers that will be replaced by new ones) and become flightless for about three weeks. Males also may begin to court female mallards, while the later part of Summer is spent preparing for migration. Then they begin to nest in grass cover near or around wetlands. Mallards are usually monogamous, but sometimes males pursue other females in forced intercourse. They have also been observed having sex with other males, and eve take part in necrophilia. (More information here). Because mallards are found in many public places, some have become very approachable to humans, though they are generally territorial to each other (“All About Birds”, Cornell University).

Observation

Second Observation excerpt

“Female keeps ducking under water near log, almost appears as if she is back flipping, though I assume she has found some sort of food. She comes up with a few head bobs and picks at back feathers. Male swims behind paying no attention. They tend to wiggle tail feathers, put their head down, and pluck at chest. When they take off to fly, they almost run along surface of water. Male sizes up and flap wings frantically. Other male duck copies the movement, but they still pretty separated.”

Third Observation Excerpt

“Male swims off in distance. He keeps dipping down under surface with his tail feathers in the air, comes up, shakes water off. Head is shiny and iridescent. Stands up and flaps wings, but doesn’t fly away. I don’t hear him making much noise, just swims around in big circles frequently stopping to pick at feathers. Looks around, dips under surface of water.”

Reflection Excerpts

“The ducks don’t seem to have much variety in behavior that I am seeing. The movements they make are continuously repeated, such as the head bobs and the feeding. It’s almost ritualized it seems to me, like some weird dance stuck on repeat. It’s like clockwork. I’d like to see them interact more with each other, generally it looked like they just minded their own business.”

“This is an incredibly boring task. I can’t find myself able to focus on the ducks because I have no patience in watching them swim around in circles. Is it wrong that I want to see them in an all out duck brawl, or some mating, or anything that isn’t swimming and looking for vegetation under the surface of the water.”

Visual Research

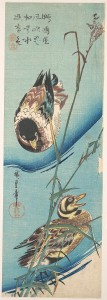

Hiroshige, Utagawa. Mallard Ducks and Snow Covered Reeds. 1843. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Hiroshige, Utagawa. Mallard Ducks and Snow Covered Reeds. 1843. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Description: Two ducks stretched across the canvas, one closer to middle top and one towards bottom right. The canvas is covered in shades of blue with green reeds coming up from the bottom left, extending all the way up to the top right.

This is Japanese representation I found from the 1800’s. The piece is beautiful. I’m especially drawn to the color patterns on the mallard at the top. The wing is all blue, which could be a highlight of the speculum from the artist. I also get a sense of separation between these two ducks, with the darker line of blue between them.

Heaphy, Thomas. Still Life with Rabbits and Mallard Drake. 1806. Fine Arts Museum of San Fransisco.

Heaphy, Thomas. Still Life with Rabbits and Mallard Drake. 1806. Fine Arts Museum of San Fransisco.

Description: Dead mallard resting in basket of hay with two dead rabbits. Most of the image is contained in the center of the canvas.

This piece depicts a dead mallard, something I found very common in doing visual research. I think this image is very evocative. It gives a sense of these animals as being prey, or even food, but it’s done in such warm colors it almost feels inviting. I don’t want to be drawn to it, but I am. It feels calming, even though it depicts dead animals. It seems to almost represent the respect hunters have for the animals they consume.

Eastern Sioux. Pouch. 1810-1830. The Detroit Institute of Art.

Eastern Sioux. Pouch. 1810-1830. The Detroit Institute of Art.

Description: Pouch made from buckskin, mallard duck scalp, porcupine quills, tin cones, dyed deer hair.

I wanted to include this piece because it is physically crafted from part of a mallard. I never knew that mallards were ever killed and used as material for pouches, or clothing, or jewelery, and I think it’s important to represent that if they are. I find myself favoring the area of this pouch that is made from mallard scalps because of the iridescence and coloring, it’s oddly just as beautiful in this context. I am left wondering if there is any specific reason for using the mallard aside from the decorative traits.

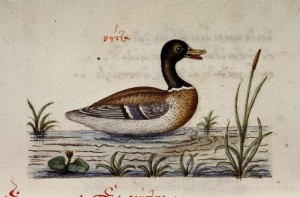

Philes, Manuel. De Ammimalium Proprietate. 1564. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

Philes, Manuel. De Ammimalium Proprietate. 1564. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

Description: A mallard duck in the center of the canvas, sitting above water with it’s bill slightly open. There are numerous grass plants along the bottom border and white space as the top.

This was an early representation I found of the mallard. The color is interesting to me. It’s less vibrant than what I’m used to seeing for a male, but the white line across his neck makes me think that it is in fact a male. I like the way it just floats on the water and almost looks to have no legs because when watching them swim, it’s almost as if they really don’t. I’m find myself being a little distracted by the duck’s face in this image, for some reason. It almost looks exaggerated.

Creative Writing: 3 Part Invention

Part 1

You are a smear of green and blue across the still water, a highlight of color in the drab world around me. You float amongst the ripples, causing chaos around as you dip your body underneath the water, leaving nothing but your tail feathers standing proud in the air. Your bill breaches the surface for a moment before returning below only to appear again. Your partner, in a brown cloak, swims past and you nearly waltz around each other before separating.

Part 2

I wonder if you see me the way I see you. On my ledge I watch your decorative colors pass by, and I wonder if I could ever pull it off like you. I doubt you even realize the vibrancy of your head feathers but my eyes fixate on them and watch as the sun shines off the iridescence. You focus on the water and I focus on the beauty.

My legs are cold and stable on the ground below and the wind cools my bare skin. I don’t think we could be any more different. You seem so content and my mind begins to waver to distant lands as you bob your head for the hundredth time. I find myself annoyed by your predictable routine, but still slightly transfixed in your patterns.

Part 3

An entire world separates us. I couldn’t begin to imagine your aquatic life or even your nests. You survive on what you need and I rely on excess. Your eyes are unreflective and unreadable. I think you’re happy, but I don’t know.

Resources

All About Birds. Cornell University. Web. 21, May. 2012

Merne, Oscar. Ducks, Geese, and Swans. New York. St. Martin’s Press. 1974. Print.

National Geographic. n.d. Web. 21, May. 2012

Miller DB and Gilbert Gottlieb G. “Maternal Vocalizations of Mallard Ducks (Anas Platyrhynchos)” . Animal Behaviour. Volume 26, Part 4, November 1978, Pages 1178-1194.

Waterfowl Hunting. n.d. Web. 21, May. 2012.

Johnsgard, Paul. “A Quantitative Study of Sexual Behavior of Mallards and Black Ducks”. University of Nebraska, Papers in Orinthology. Pages 133-155

DL, Ashliman. Folklore and Mythology. 2012. Web. 21, May. 2012.