Larus Smithsonianus/Argentatus*

Introduction:

The American Herring Gull is the stereotypical seagull. By that I mean that it is the creature that people usually imagine when they hear the word “seagull.” With their white plumage, grey wings, and yellow beaks with red dots, Herring Gulls have become the ubiquitous image for all seagulls due to their distinctive look and widespread distribution. It was this frequency that helped me decide to pick the Herring Gull as my animal to observe. These birds, as opportunists by nature, have adapted very well to human expansion, and can be seen anywhere where food can easily be found. In my case, it was the Target parking lot.

The American Herring Gull is the stereotypical seagull. By that I mean that it is the creature that people usually imagine when they hear the word “seagull.” With their white plumage, grey wings, and yellow beaks with red dots, Herring Gulls have become the ubiquitous image for all seagulls due to their distinctive look and widespread distribution. It was this frequency that helped me decide to pick the Herring Gull as my animal to observe. These birds, as opportunists by nature, have adapted very well to human expansion, and can be seen anywhere where food can easily be found. In my case, it was the Target parking lot.

For more information, check out the American Herring Gull Wikipedia page.

Natural History

Order: Charadriiformes

Charadriiformes are a large and diverse order of aquatic birds. They are generally found along seacoasts and inland waters. Many charadriiformes are shorebirds or diving birds. (Pons, Phylogenetic relationships within the Laridae (Charadriiformes: Aves) inferred from mitochondrial markers).

Family: Laridae/Larinae

The Laridae family is composed of gulls (Pons, Phylogenetic relationships within the Laridae (Charadriiformes: Aves) inferred from mitochondrial markers). Gulls are classified by their medium to large size, long bills, webbed feet, and harsh squawking calls. Gulls have unhinging jaws (Anonymous, What Are Gulls?).

Genus: Larus

The Larus genus is a large genus of gulls with worldwide distribution (de Kniff, 402). The gulls of the Larus genus are large, grey or white, and often have black markings. It is essentially considered the default genus for gulls (Anonymous, Gulls Identification Page).

The American Herring Gull is distinguished from other gulls by its relatively large size, stout, blocky head, and habitat in North America. These gulls take around 3-4 years to mature. American Herring Gulls look remarkably similar to European Herring Gulls, but the two may not be related; the taxonomy is sketchy at best (de Kniff, pg. 404).

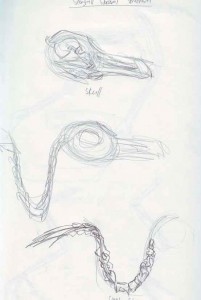

Herring Gulls are generally around 25 inches long and between 1 1/2 to 3 pounds. They have a stout, round but muscular body and a blocky head with a large, heavy bill. Their skulls are relatively thin and dominated by the beak, with large ocular openings. Herring Gulls have white bodies, grey wings with black tips and white stripes, yellow beaks with red dots on the underside, and orangey-pink feet when they are adults (Anonymous, What Are Gulls?). As juveniles, Herring Gulls are a speckled brown, grey, and white, with black bills and feet. Their colors gradually shift as they age, with most developing their full adult plumage in their 4th year (Vanner, pg. 112).

Herring Gulls are generally around 25 inches long and between 1 1/2 to 3 pounds. They have a stout, round but muscular body and a blocky head with a large, heavy bill. Their skulls are relatively thin and dominated by the beak, with large ocular openings. Herring Gulls have white bodies, grey wings with black tips and white stripes, yellow beaks with red dots on the underside, and orangey-pink feet when they are adults (Anonymous, What Are Gulls?). As juveniles, Herring Gulls are a speckled brown, grey, and white, with black bills and feet. Their colors gradually shift as they age, with most developing their full adult plumage in their 4th year (Vanner, pg. 112).

Herring Gulls usually make loud, harsh, “HYAH” sounds, which is called “keening.” They will also squawk and croak, and will make loud, ululating calls to ward other animals off (Vanner, pg. 112).

American Herring Gulls can be found all over, wherever there’s water or people. They live all along the East and West coasts of the United States and Canada, and can be found as far inland as Oklahoma (Vanner, pg. 112).

American Herring Gulls are diurnal scavengers that will eat anything, from garbage to the young of other gulls. They generally breed from March through April, and will make nests out of whatever grass and twig-like objects are available. Nests will usually carry around 2-3 eggs. American Herring Gulls are opportunistic omnivores and are aggressive space-takers that tend drive out other smaller, weaker species when they are in large groups (Vanner, pg. 112).

Around 300,000 years ago, in the Paleolithic era, an ancestral population of progenitor gulls was split into two groups. One group drifted toward the North Atlantic, while the other remained in the Aralo-Caspian area (Clade 1 and Clade 2, respectively.) Coincidentally, this is around the same time that Homo Sapiens evolved. Around 122,000 years ago, the North Atlantic population expanded, resulting in the European Herring Gull. 25,000 years ago, this group is believed to have diverged into the American Herring Gull (de Kniff, pg. 403).*

Observation Excerpts

Cultural History

Gulls in the western perspective are very often considered to be foolish, awkward clowns and opportunistic scavengers. But there are far more depictions of gulls than just these two personas due to the various relationships and observations people have made throughout history as the gulls and their cultures intersected.

For example, in the Haida myth “Kai,” a woman flees from her jealous husband to her brother’s village, only to be separated from the village by a flood. The woman becomes so distraught that she tries to kill herself, only to be stopped by a seagull. The gull convinces her to live, then tells her to heat a small stone and swallow it. The woman does as she is bid, and later gives birth to a son, who becomes an invulnerable hero. In this myth, the seagull serves as a wise guardian and an adviser with strong spiritual power (Boaz, pg. 622-623).

Remarkably though, the seagull is viewed much differently in another Pacific Northwestern Native American myth. In this story, the Great Spirit created all things and stored them in cedar boxes, which he gave to all of the animals that existed before humans. Seagull was given the box that contained all light. Seagull coveted his box, and would not open it, no matter how much everyone pleaded with him. This caused Raven to take matters into his own hands, and he drove a thorn into Seagull’s foot, where he tortured him until Seagull dropped the box and spilled out all the light. Almost counter to the Haida myth, in this story the seagull is selfish and cruel, only caring about itself, even to the detriment of others (Judson, pg. 56).

A third Pacific Northwestern Native American myth from Tsimshian tribe depicts seagulls in what is perhaps the most similar presentation to Western perspectives. In the Tsimshian story, Raven catches some small fish and cooks them over a fire. But some seagulls notice the cooking fish, and steal them Raven and eat them. Outraged, Raven throws the gulls into the fire, singeing their wings. In this story, the gulls are merely opportunistic scavengers without much motive to their actions (Boaz, p. 88-91).

Gulls also featured quite frequently in Welsh mythology. In the tale of St. Kenneth of Wales from Catholic myth, St. Kenneth was abandoned at sea as a baby. But a flock of gulls found him and brought the infant to their island, where they raised Kenneth until he was a young man. In this story, the gulls simultaneously represent the hand of God and parental instincts (Anonymous, Come and See Icons).

Gulls in Welsh mythology were also seen as harbingers of the storm. Whenever one was seen wheeling overhead, it meant that a storm would soon strike that exact area. So to the Welsh, gulls were also a divine animal with magical or preternatural powers. (Anonymous, Fairies, Witches, Devils Welsh Myths and Legends).

In the Finnish epic, the “Kalevala,” the hero-smith Ilmarinen captures the daughter of his rival, Pohjola, with the intent to marry her. But Pohjola’s daughter hates, despises, and annoys Ilmarinen so much that he magically turns her into a seagull rather than put up with her. In this myth, the gull is seen negatively, where being one is considered equivalent to grievous punishment (Anonymous, Kalevala).

In Mormon mythology, the early settlers of Utah’s first crops were going to be wiped out by locusts, dooming the settlers to starve. But miraculously, an enormous flock of gulls descended upon the locusts and ate them all before the crops were touched. Here, seagulls were once again seen as the hand of God and California Gulls, the suspected species of the flock, have been venerated as Utah’s state bird (Schlosser, American Folklore).

In 1878, the writer and biologist John Hogg catalogued many of his experiences with animals in a book titled “The Parlour Menagerie.” Among the many animals he observed were two Herring Gulls that were kept as pets, “Topsy” and “Snow.” Hogg demonstrated much fascination and humor toward the gulls, and attributed a lot of intelligence to them. (Hogg, pg. 383-387).

The writer John Service was similarly struck by gulls, as evidenced by his poem “Grey Gull.” Throughout the poem, Service describes the delicate beauty of a Herring Gull wracked with age and hardship, and claims that it told him a story. Here, the gull is beautiful, wise, mysterious, and eloquent. (Service, Poetry Archives).

Franklin Russell, another writer and biologist, wrote the story “Argen the Gull,” the fictionalized and anthropomorphized story of a Herring Gull’s life. Russell writes with immense respect for the Herring Gull, and paints his story’s protagonist, Argen, with the qualities of nobility, intelligence, protectiveness, and strong physical qualities, while still keeping a relatively naturalistic depiction of a Herring Gull’s life. (Russell, pg. 3-239).

From a modern cultural perspective, while still seen as goofy and thieving, gulls are also still seen with a certain reverence. Take “The Ultimate Guide to Birds of North America,” for example. This book covers many birds from throughout the United States and Canada, both common and extraordinary, including the Herring Gull, and treats them all with the same levels of respect (Vanner, pg. 112).

In addition to that, all seagulls in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom are protected by Wildlife Conservation laws. So even if we do see gulls as silly, roguish, or even pests, they as a whole are still seen in many cultures as creatures worth having around (Wickstrom, Questions About Seagulls).

Eight Gulls

There are eight gulls in front of me. Only two of them are adults. The other six are juveniles, and of those, only four have not yet begun to molt. The remaining two young adults are caught in a transitional stage, combining the features of the rest of the flock. They are mainly brown, like the younger ones, but their plumage is covered in flecks and spots of white that show what color they will soon become. Even their heads are all white. Their beaks are black, again, just like the youngest gulls, but their feet are the same orangey-pink as all the others. The oldest gulls look the most different, with stark white bodies, light grey wings, and yellow beaks tipped with a dot of red on the bottom. The tips of their wings are dark grey and striped with white. The youngest are a patchwork of brown. All eight of the gulls are huddled close together, squawking, stretching, and preening, but one by one, each one stands and flies away. Soon, all are gone except for one adult and one juvenile, who sit together in the fourth parking space to my right. The eight are now two.

Where are you gulls? Where have you gone? What reason did you have to get up and go, leaving your mother and father, or brothers and sisters, or children behind? Were they even your family at all, or did you just gather due to common interest, only to leave when these interests became much less common later? Or was there somewhere you’d just rather have gone? Somewhere where something was just ripe for the taking, I’d bet. That’s all that motivates you gulls anyway. Food. Or at least, that’s what we like to think. But you always take things that no one needs all that much, either. It’s not like fries are all that important in the long run, and everybody’s gotta do something to survive. You’re not even hurting anyone. Just because you don’t fit our human standards of nobility doesn’t make you bad, or without worth. But I’ll never really know where you’re coming from either. You’re a bird and I’m a human. I want to know you, but will I ever really try? And if I do, can I even cross that gap? All birds can see what I cannot. A whole other spectrum is available, to see and to know. But humans can’t see in ultraviolet light.

But I do know that I saw eight gulls. Then seven, then six, and less and less until only two remained. Both of them sitting in the fourth parking spot to the right. It’s kinda funny. Four. That’s the number of death in Chinese culture. Or at least Cantonese. And white’s the color of death. Almost makes me wonder if the seagulls are trying to tell me something. If the old one and the young one know something that I do not. My dad and I always had a lot of fun talking about the different meanings of the numbers and colors in Chinese culture. Like how red stands for luck and how eight means “prosperity.” That’s pretty funny, actually. Eight seagulls. I hope that means something good. And that parking space four and the white gulls don’t mean anything bad. But hell, even if they do, for death-birds, they’re pretty darn cute. I’ve always thought that. When I was younger I used to dream about catching a seagull for myself. Just last quarter I was joking, or maybe even half-joking, about luring gulls into a dog kennel and keeping one as a pet. Of course, I doubt it would’ve worked. The birds are smart, and if they can recognize a McDonald’s bag from a mile away, I’m sure they could see a trap. That’s another thing I love about them; they’re quite intelligent. Smart and greedy, sneaky and silly, seagulls always embodied my favorite tropes of the wandering vagabond and rogue. I always kind of wished I could be like them.

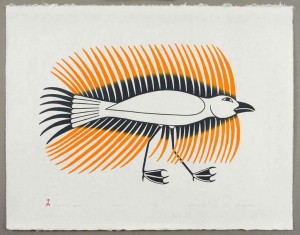

Ashevak, Kenojuak. Quivering Seagull. 2004. Richard F. Brush Art Gallery, St. Lawrence University, New York. ARTstor. Web. 15 April 2012.Anonymous. “Kalevala.” SKS Finnish Literature Society. Web. 8 May 2012.

Boaz, Franz. Tsimshian Mythology. Washington D.C., Smithsonian Institution, 1910. Print.

Clark, Ella E., Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, University of California Press: 1953. Print.

de Kniff, Peter et all. “The Berlington Convention: Speciation in the Herring Gull Assemblage of North America.” Biology of Charadriiformes. 7 June 2005. Web. 9 May, 2012.

Drisdelle, Rosemary. “Folklore of Seagulls- Myths and Old Stories.” Birds @ Suite 101.Web. 8 April 2012.

“Gulls Identification Page.” Mersey Birders. Web. 9 May 2012.

Havell, Robert. Herring Gull, with view of Entrance to St. Augustin. 1827-1838. New York Historical Society. ARTstor. Web. 8 May 2012.

Hogg, John. The Parlour Menagerie. London, John Hogg: 1878. Print.

Jones, Thomas. The Bard. 1774. National Museum of Wales, UK. Art Collections Online. Web. 8 May 2012.

Judson, Katherine Berry. Myths and Legends of Alaska. Bibliolife, LLC. Print.

“Larus Smithsonianus.” Tree of Life web project. Web. 9 May 2012.

Pons, J-M et all. “Phylogenetic relationships within the Laridae (Charadriiformes: Aves) inferred from mitochondrial markers.” Science Direct. 22 April 2005. Web. 9 May, 2012.

Russell, Franklin. Argen the Gull. New York, Knopf: 1964. Print.

“Saint Kenneth of Wales.” Come and See Icons. Web. 8 May 2012.

Schlosser, S. T. “The Gulls.” American Folklore. Web. 8 May 2012.

Service, Robert. “Grey Gull.” Poetry Archives. Web. 8 May 2012.

“The Seagull, Birds and Beasts in Welsh Folklore and mythology, a tale from Gwydellwern Wales.” Fairies, Witches, Devils Welsh Myths and Legends. Web. 8 May 2012.

Tinbergen, Niko. The Herring Gull’s World. New York, Harper Torch Books: 1960. Print.

Vanner, Michael. The Ultimate Guide to Birds of North America. Bath, UK, Parragon: 2011. Print.

“What Are Gulls?” wiseGeek. Web. 9 May 2012

Wickstrom, Steven P. “Frequently Asked Questions.” Questions About Seagulls. Web. 8 May 2012.

*Note: Debates are currently being undertaken as to whether or not the American Herring Gull is of its own species (Smithsonianus) or a subspecies of the European Herring Gull (Argentatus).