Tamias townsendii

Tamias townsendii

studied by Ruth Hayes, April-May 2012

Introduction

Townsend’s chipmunks live in our back yard. So far we’ve observed two of them. We believe they are a mated pair. They seem to have built a nest in a large brush pile near the compost bins that we intend to chip for mulch. We’ve postponed that plan, not wanting to destroy a nest that may have young in it.

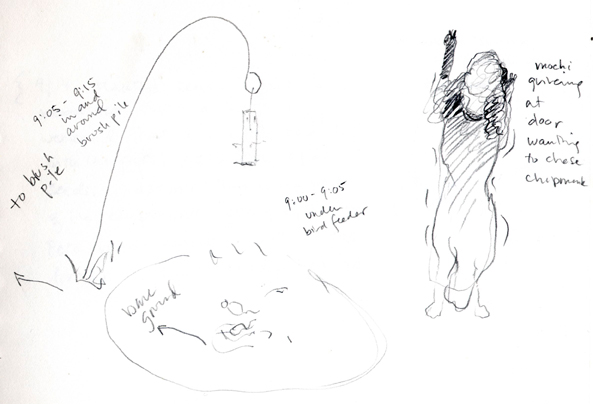

I decided to observe the chipmunks (one at first, before I realized there are two) because I often see them from the kitchen window scavenging sunflower seeds that have dropped from the bird feeder. So they are accessible and frequently visible. Also, I’m intrigued by how bold they are in the face of our dog, a miniature black poodle named Mochi. They seem to tease her, always staying just out of reach, or coming up to the glass sliding door while she’s on the other side of it unable to get at them. I was also interested in working with an animal that is considered cute. Mary Oliver wrote that “… nothing in the forest is cute” so I want to challenge myself to represent this animal, exploiting its cuteness as little as possible (91).

Natural History

Townsend’s chipmunk has rich brown fur with four pale and three dark stripes that run down the back and from the nose past eyes and ears. The tail has thinner fur, it’s belly and ventral parts tend toward tawny or white fur. Typically about 6″ long with a 5″ tail and weighing between two and five ounces, it inhabits dense forests. Mathews (221) describes Townsend’s as the “most conspicuous forest mammal – diurnal, noisy and abundant.” It’s vocabulary consists of chips, chirps and tisks. These are frequently alarm calls.

The photo above is of a skeleton of an Eastern Chipmunk, prepared and photographed by “Boneman_81”. Eastern Chipmunks vary only slightly from Townsend’s in coloring. There are other species of chipmunks, all in North America with the exception of the Siberian chipmunk. Townsend’s species have been divided into four sub-species that range along the Pacific Coast from British Columbia to Northern California.

The photo above is of a skeleton of an Eastern Chipmunk, prepared and photographed by “Boneman_81”. Eastern Chipmunks vary only slightly from Townsend’s in coloring. There are other species of chipmunks, all in North America with the exception of the Siberian chipmunk. Townsend’s species have been divided into four sub-species that range along the Pacific Coast from British Columbia to Northern California.- Chipmunks are semi-arboreal cousins of squirrels that nest in burrows or trees. They forage for seeds, berries, insects, underground fungi and have been known to eat bird’s eggs and nestlings.They store large quantities of food, transporting it to caches in their cheek pouches. Instead of hibernating, they enter into 4-5 day long torpid periods from which they awaken to eat from their stores and excrete.

- Townsend’s chipmunks have a 30 day gestation period. They are born naked, blind and helpless. Juveniles leave the parental nest after about two months and then begin to forage and build up their own stores for winter.

- Cultural History

The word “chipmunk” derives from Eastern Algonquin language (McDavid, 248-256). Chipmunks are minor characters in Native American lore, however there are Iroquois, Winnebago and Seneca stories that explain for example how chipmunk got its stripes and why it stores food for the winter. In one, chipmunk is represented as an impertinent trickster whose chiding of bear results in a swipe that leaves bear-claw stripes down its back. - I like this story reprinted on “hotcakencyclopedia.com” from Oliver LaMère and Harold B. Shinn’s Winnebago Stories: “In the time of beginnings, the good spirits and the evil spirits met in council to determine how the world should be divided between them. First they took up the question of how many moons there should be from one winter to the next. Wild Turkey (Zizikega) strutted before them and spread his tail feathers, declaring, ‘Let a year be as many moons a there are spots on my tail.’ But the council of spirits voted this down, as there were far too many spots on his tail. Partridge also suggested that there should be as many moons in a year as there were spots on his tail, but the spirits felt that it was also too long a time. Then Chipmunk (Hečgenįka)scampered up throwing its tail over its head as chipmunks always do, and said, ‘Let a year be as many moons are there are black and white stripes down my back.’ The counselors thought well of this suggestion, and allowed that the six black stripes would be the summer moons, and the six white stripes would be the moons of winter.”

-

In a Micmac story, a witch protects her adopted son by skinning a chipmunk and instructing it to go ahead of a boy to be able to warn him when danger is near. (Parsons,55). Chipmunk performs similar protective acts in a Nez Perce story about how the woman Watkuese travels back home from the east. He creates fog to help her hide when she is in danger. (Clark, 175-178).

I discovered a personal connection with the modern cultural history of chipmunks. My mentor at Cal Arts, Jules Engel, used to work at Format Films, the studio that produced the original television version of Alvin and the Chipmunks. I remember that when I first learned this, I was somewhat shocked and disillusioned. How could someone with such a modern, inventive aesthetic work on such a silly cartoon show? Jules’ beautiful animations were all about abstraction, movement and temporal composition.

I discovered a personal connection with the modern cultural history of chipmunks. My mentor at Cal Arts, Jules Engel, used to work at Format Films, the studio that produced the original television version of Alvin and the Chipmunks. I remember that when I first learned this, I was somewhat shocked and disillusioned. How could someone with such a modern, inventive aesthetic work on such a silly cartoon show? Jules’ beautiful animations were all about abstraction, movement and temporal composition.  But of course Jules, whose specialty was color design, had to survive like any artist and so he worked on a lot of studio animation, including Disney’s Fantasia (1940) and many of the wonderful, groundbreaking cartoon modern films produced by UPA in the 1950s.

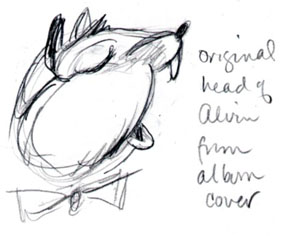

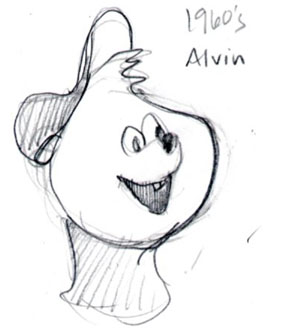

But of course Jules, whose specialty was color design, had to survive like any artist and so he worked on a lot of studio animation, including Disney’s Fantasia (1940) and many of the wonderful, groundbreaking cartoon modern films produced by UPA in the 1950s. - I sketched these three studies of the Alvin character designs based on images posted on the Animation Resources web site and the web site for the most recent Alvin and the Chipmunks movies. I’m interested in the different levels of anthropomorphism in each, especially how the nose recedes from the length typical of most rodents, to a sort of dog-like snout, to a minimal stub at the end of a central nasal stripe.

The ears also migrate from the top of the head to the sides, and towards the back of the skull, so by the contemporary version, the ears are positioned in nearly the same place as most humans’ ears.

The ears also migrate from the top of the head to the sides, and towards the back of the skull, so by the contemporary version, the ears are positioned in nearly the same place as most humans’ ears. - The 1950s Alvin has typical chipmunk coloration. The 1960s version is a uniform tawny brown. The contemporary Alvin has a much lighter complexion and, because the animation was produced in 3d computer software, the designers used different levels of saturation of color to model the face and emphasize its roundness, softness, and his youth. In his essay “A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse” Stephen J. Gould notes how that character’s look became progressively younger from his origin in the 1920s to his design in the 1970s (95). I see this juvenilization, or neoteny, in the three versions of Alvin.

- Summary of observations

I began sporadic observations of the chipmunks during the second week of April taking advantage of their habitual foraging in front of our kitchen window and underneath two of the three bird feeders to watch them in the mornings before, during and after breakfast. If I kept the dog inside, the chipmunks would up to an hour or so traveling back and forth from the kitchen feeders to the one on the drain field. We placed a river rock at the corner of the flower bed directly opposite the kitchen window. It’s about two feet high. A chipmunk will frequently perch there, watchful, before darting under the feeder to get sunflower seeds (see video below). Other times, a chipmunk will race across the patio just a few feet from the kitchen sliding door, forage under the third bird feeder over by the drain field, or climb up the madrone that stands between the feeders. Also foraging under the feeders are towhees and juncos. There doesn’t seem to be much interaction between rodents and birds. - One late April morning I saw two chipmunks weaving in and out of the brush pile, chasing each other intermittently. The brush pile is about 6 feet high. Sometimes a chipmunk would appear at the highest point, other times it would show up closer to the base. Female Townsend’s chipmunks are commonly larger than males (Edelman & Koprowski), but these two appeared the same size so I couldn’t tell if they were male or female, or different sexes but the same size.

- They left evidence of their activities all around the yard. In early April I planted beans to sprout in pots in the woodshed. The following weekend I discovered that some creature had dug into them-each pot had a neat hole the depth at which I’d planted the seeds. I assume it was a chipmunk that had dug them up. Two years previously I’d experienced the same thing with peas I’d sown directly into the ground. Now I start the peas inside. During the third week of May, one large and two small chipmunks were observed near the kitchen feeders. We assumed that the smaller ones were juveniles, and concluded that the pair of chipmunks seen earlier were mates. The first weekend of June we found a dead female near the fire pit. Her fur was matted and ragged and her eyes were already whited out and collapsed. We couldn’t see any signs of mauling, however. She had been lactating; six white enlarged nipples protruded from the hair on her belly. It was a mystifying and sad ending to this period of observation.

I made this short video from two photos shot by Peter Randlette of one of the chipmunks sitting on a rock outside our kitchen window. Chipmunks move so quickly that it’s hard to see “inbetweens” in the transition between two similar poses. So to simulate live-action footage, I put the photos into After Effects as an image sequence and used a combination of masks, noise effects and blur and the puppet tool to create the illusion that its nose is twitching. My main intention was to represent the chipmunk in its “pure animal” form, a category of Wells’ Bestial Ambivalence.

Sources:

Boneman_81, http://www.flickr.com/photos/26485684@N08/sets/72157621088741196/ downloaded 5/17/2012

Clark, Ella E., “Watkuese and Lewis and Clark”, Western Folklore , Vol. 12, No. 3, Oregon Number (Jul., 1953), 175-178).

Edelman A.J. and Koprowski, J.L., “Influence of female-biased sexual size dimorphism on dominance of female Townsend’s chipmunks”, ag.arizona.edu/~squirrel/CJZ%20dimorph%20in%20Chips%2007.pdf, 2007, downloaded 6/4/2012

Gould, Stephen J, A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse, The Panda’s Thumb, Norton, 1980, 95

hotcakencyclopedia.com, from Oliver LaMère and Harold B. Shinn’s Winnebago Stories (New York, Chicago: Rand, McNally and Co., 1928) 91-99, downloaded 5/28/2012

Mathews, Daniel, Cascade-Olympic Natural History: A Trailside Reference, Raven Editions, 1992, 221

Oliver, Mary, A Few Words, Blue Pastures, Harcourt Brace, 1995, 91

Parsons, Elsie Clews “Micmac Folklore”, The Journal of American Folklore , Vol. 38, No. 147 (Jan. – Mar., 1925), 55-133

Ransom, Jay Ellis, Harper and Row’s Complete Guide to North American Wildlife, Western edition, 1981

Raven I. McDavid, Jr., American Speech , Vol. 26, No. 4 (Dec., 1951), 248-256

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture, Rutgers University Press, 2009, 51