In order to truly understand the evolution of textiles in the colonized British Isles, it is important to look at some of the indigenous cultures that played an integral role in the evolution of textiles in that region and globally. Because the societies of both Ireland and Scotland have some very distinguished differences per county and region, I will not be able to cover ever single element of traditional dress in Ireland and Scotland. I will, however, cover one of the more significant textile cultures that has come up in my research time and time again – that being of the Aran Islands.

The Aran Islands are a small archipelago that sits just off of the costs of Co. Clare and Co. Galway. Due largely to their isolated nature and lack of significant resources, British colonization and Western influence did not quite make it to the islands until relatively recently. In fact, the population of the Aran Islands alone makes up for a very solid portion of the population that speak Irish as their native tongue. With modernization and new modes of transportation there is much more back and forth between the mainland and the islands now and a movement away from traditional dress has already occured, however, they remain a culture of their own and have a rich history of unique traditional dress.

The most notable contribution of Aran culture is the “Aran Knit Jumper,” or “ganseys” as they’re called in Irish. This design was and still is an element of men’s traditional wear – specifically that of the fishermen of the island. A common tale is that different patterns in the cable knit sweater signified different Irish families so that a fisherman’s body could be recognized if found washed ashore, and another less popular one is that they symbolized different charms. There is not an exact record of when the gansey became a staple of Aran wear, however, the myths of the significance of family patterns has been traced back to a J.M. Synge play where a woman recognizes her lover’s body by a dropped stitch in the garment she knitted him. This play was written in 1904, and it is likely that those already producing Aran knits for sale used it as a clever marketing snippet.

There are lots of different folk stories surrounding Aran sweaters, and what wasn’t true before seems to have fibbed its way into truth in the modern era. What is particularly historic and special about the knits from this region is that they are not scoured to remove the lanolin from the wool before spinning. This creates a yarn that is much harder to work with, but also adds a water resistant quality to the garment that is knitted for it – which is important for an economy that was historically based on fishing in incredibly rough, stormy weather.

Since its widespread marketing starting in the early 20th century, Aran sweaters have become arguably the most recognizable aspect of Irish fashion. Today, Blarney Woolen mills takes over the tourist market in Ireland, while globally, companies like L.L Bean have created lines using aran knits and fast fashion stores like H&M and Forever 21 have created knits that mimic the traditional cable knit pattern. Through all its expansion, in order to be called a true Aran knit sweat, the garments still must be hand knit in the Aran islands.

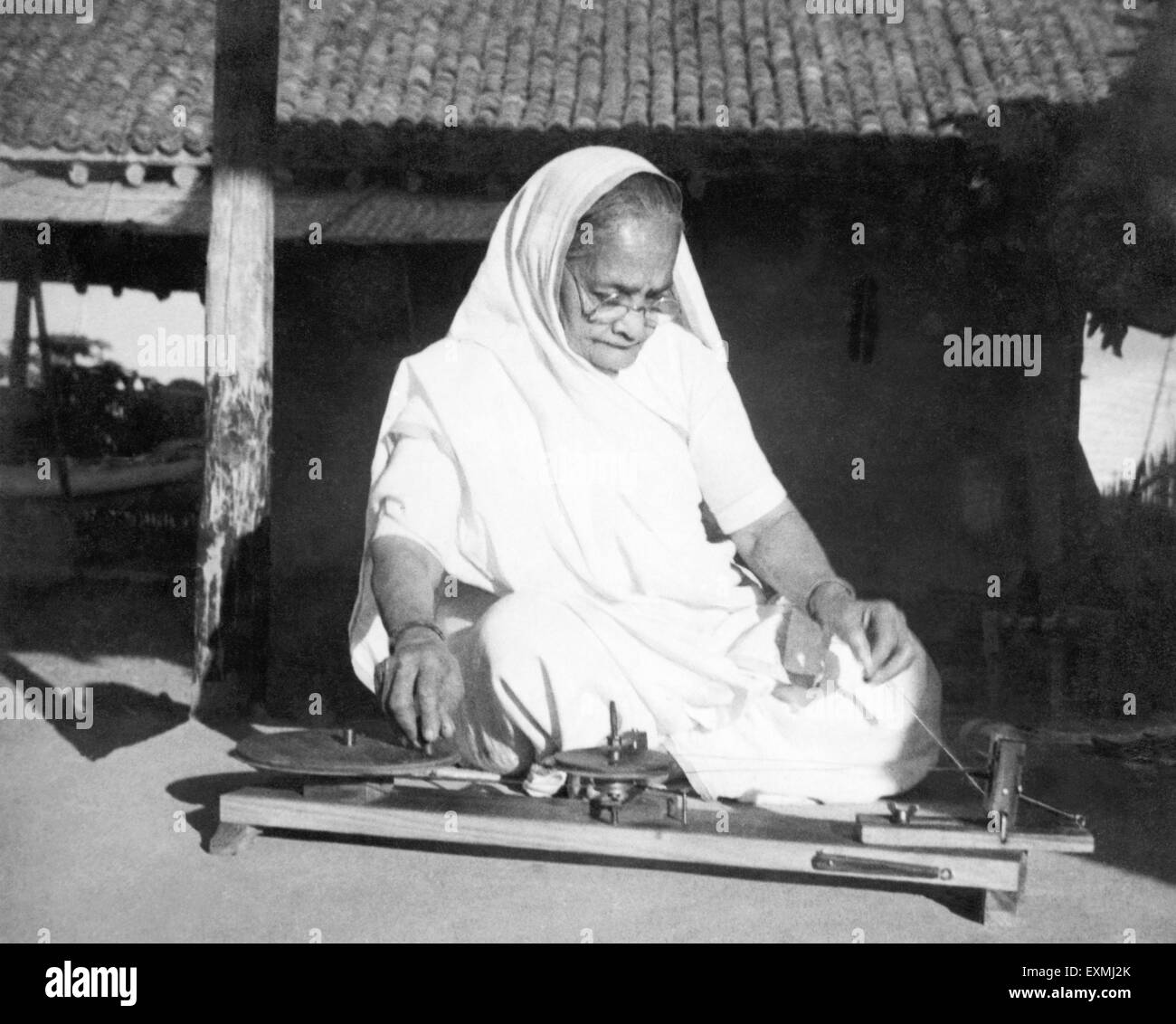

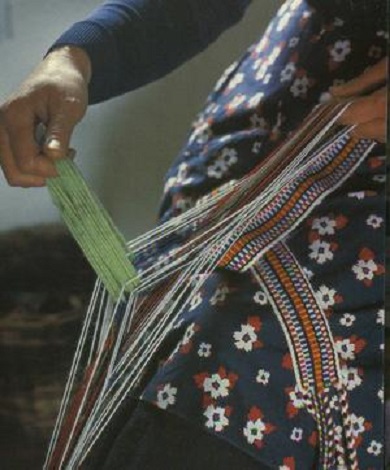

Moving away from the more globally recognized products, most people are surprised to discover how colorful the tradition lady’s dress is. This is mostly because of the monopoly that ganseys have on Aran clothing in the public eye. In reality, however, the only reason that those sweaters are not dyed is because they are the equivalent of work wear anywhere else. Formal dress on the islands was much more detailed and colorful – specifically those for attending mass. A piece of clothing that is all but forgotten to the modern world is the ‘crios belt.’ According to David Shaw-Smith in his exploration of Irish crafts in Ireland’s Traditional Crafts crios belts were created by “stretching the warp threads between two chairs or stools – or, more traditionally, between one hand and one foot, tying the ends to the shoe – making the length 3 1/1 yards if the crios is to be worn by a man and 2 yards if by a woman. It is customary to have two white threads on each outside selvedge, using perhaps five or six different colors between.” (Shaw-Smith, p. 27) These garments were often worn on wedding days and were even used to bind the wedded couple’s hands together. Like with any traditional garment, these belts were dyed using natural materials from the islands; mainly mosses and lichens from the shores.

Today, the globalization of the textile chain has unfortunately made the textile traditions of the Aran Islands a bit less about creating something that is of the islands in its essence, and more about creating a product that can be marketed as such. In the case of Aran jumpers, the wool is often from sheep that are raised and sheared in Australia – one of the world’s top wool producers – and processed into roving (and sometimes dyed) in China. It isn’t until the actual spinning and knitting portion of the chain that the fiber makes its way to Ireland to become the product that is world famous for being conceived on the islands. Unfortunately, the islands (nor the mainland itself) do not have the resources to create a product that is easily digestible for tourists looking to bring home each and every family member a jumper at less than 100 euro each. In some ways, the sweater and tourism industry has revolutionized the rough life that used to be part of the Aran Islands and has made life so much more comfortable for the people who call them their home. Unfortunately, some of the narrative of the true tradition has been lost along the way.

In another way, many young Irish fashion designers are working to bring back some of the depth of tradition in their designs while not necessarily stubbornly holding onto the past. An example of that would be the Tweed Project, a two person designer team based in Galway city. In their designs, they have payed homage to traditional aspects of Irish dress like the crios belt and tweed (of course) while still embracing modern aspects of the fashion world. Perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of this design is that they have chosen to look inward for suppliers. Instead of producing designs that are the poster child for what “traditional” Irish dress looks like for tourists to consume, they are not afraid to be unique with designs while still supporting local crafts people from fleece to frock. In this way, they are respecting the true narrative of traditional dress – not in the design but in the creation.