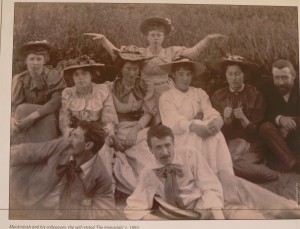

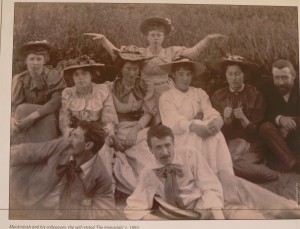

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s designs are so modern that it’s easy to forget that he was active at the turn of the 20th century. This 1893 group picture on display at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum depicts Mackintosh and his circle of friends–they came to be know as The immortals, and indeed, I believe their Glasgow Style will not soon die out, if Glasgow has anything to say about it. The city literally blooms with the Glasgow Rose, which Mackintosh and his wife Margaret used in so much of their work. A city needs its icons, they form identities, and draw interested folks to them.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s designs are so modern that it’s easy to forget that he was active at the turn of the 20th century. This 1893 group picture on display at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum depicts Mackintosh and his circle of friends–they came to be know as The immortals, and indeed, I believe their Glasgow Style will not soon die out, if Glasgow has anything to say about it. The city literally blooms with the Glasgow Rose, which Mackintosh and his wife Margaret used in so much of their work. A city needs its icons, they form identities, and draw interested folks to them.

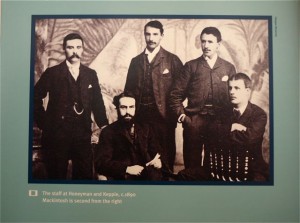

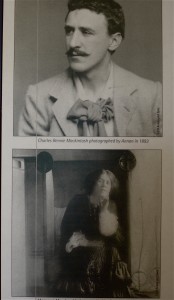

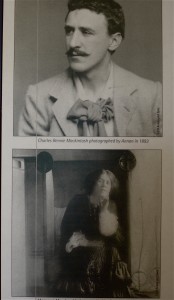

One day I walked toward the city center to the Glasgow School of Architecture. I was scheduled for the 10:00 tour– the only way one can see the inside of this Mackintosh building. Macintosh was a 41 year old “unknown” in 1909 when his design for the Glasgow School of Architecture won the competition for a new building. At the time, Mackintosh was employed during the day as a drafter in an architectural firm and in the evenings he was at the School. The School was instrumental in moving him from “drafter” to artist. There is a famous picture of Mackintosh in artist shirt and bow that represents that change in direction for him. The Glasgow School of Architecture was also important as the place where Mackintosh met his future wife, Margaret Macdonald, an accomplished artist.

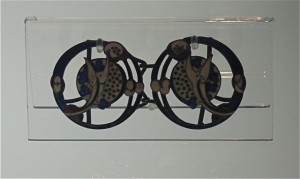

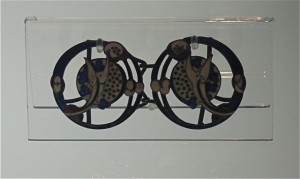

The inside tour of the building was full of lovely surprises: twists and turns and tile mosaics in concrete curved stairwells, small geometric stained glass features in doors and entryways, a warm wood carved library with distinctive furniture and lights. There is wonderful use of natural light in the studios and study areas. One bright hallway-like studio was devoted to women students back in the day. The “Glasgow Girls” as they have come to be known, had a warm, charming area to dream up their designs for jewelry, textiles, and paintings. Ann Macbeth was a teacher of needlework at the Glasgow School of Art, publishing Educational Needlecraft in 1911, and Jessie M King was a student who created textile and jewelry art in the Art Nouveau style.

Pictures were not allowed inside the Glasgow School of Art so I was constantly sketching details in my little sketchbook, hurrying to catch up with the group. Mackintosh’s winning design for the School had to be completed in stages due to funding. The building façade has classic art nouveau details; I spent a focused time attempting to capture those details in photos.

After the tour I walked a few blocks to the Willow Tea Room at 217 Sauchiehall St. The word Sauchiehall (sounds like sawhy-hawl); in Scottish Gaelic the word means willows and meadow; there is a decided willow theme throughout the tearoom. Mackintosh and Macdonald designed the building for Catherine. Cranston, a forward-looking tea house proprietor who in 1904 accepted Mackintosh and Macdonald’s fabulous design. Photos are allowed in this working tearoom; I dodged heads to capture these shots.

I enjoyed green tea and a treat called “Cloutie Dumpling with Custard Pudding,” which turned out to be a piece of gingerbread with currants smothered in a custard sauce—not too sweet.

After tea I set back to walking in the city seeking out more Mackintosh architecture—not too easy to find. The weather was very warm and Glasgow is hilly with some steep streets. I found the Daily Record Building on Renfield Lane, an alleyway, really off Renfield Street, and a tight alleyway at that. It’s a restaurant now, but its features are intact. It was difficult to get any perspective on the building’s facade in its location, but here are some details.

More city walking and I found Mackintosh’s Glasgow Herald Building tucked away on Mitchell Street. It was Mackintosh’s first public building project, built between 1893 and 1895; it’s now the Scottish Architecture Centre and called “The Lighthouse.” It has an impressive spiral staircase and a good exhibit on the Glasgow Style. An outdoor balcony gave me a chance to cool off and view Glasgow’s cityscape.

My time in the city of Glasgow remains active in my thoughts. I was nicely situated in a guest house that was located across from the well tended 85 acre Kelvingrove Park. In the morning breakfast room, I looked out at early morning tennis players. The park kindly supplied rackets and balls to players. Next to the tennis courts there was construction going on to complete a new set of lawn bowling greens. The “Glasgow 2014” online site reads that: “The Kelvingrove Lawn Bowls Centre will serve as the site for Lawn Bowls. Over a period of two years from 2010 to 2011, the facility will be upgraded to international standard with four to five bowling greens and 2,500 seats planned for competition use in the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games. Owned by the Glasgow City Council, this venue will be one of the highlights of the Games, being next to the magnificent Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum and overlooked by the equally spectacular Victorian edifice of Glasgow University.”

My time in the city of Glasgow remains active in my thoughts. I was nicely situated in a guest house that was located across from the well tended 85 acre Kelvingrove Park. In the morning breakfast room, I looked out at early morning tennis players. The park kindly supplied rackets and balls to players. Next to the tennis courts there was construction going on to complete a new set of lawn bowling greens. The “Glasgow 2014” online site reads that: “The Kelvingrove Lawn Bowls Centre will serve as the site for Lawn Bowls. Over a period of two years from 2010 to 2011, the facility will be upgraded to international standard with four to five bowling greens and 2,500 seats planned for competition use in the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games. Owned by the Glasgow City Council, this venue will be one of the highlights of the Games, being next to the magnificent Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum and overlooked by the equally spectacular Victorian edifice of Glasgow University.”