“What did I learn at art school? I learned that art is painting, not painted.” William Hollman Hunt, in an address to the London Society of Arts

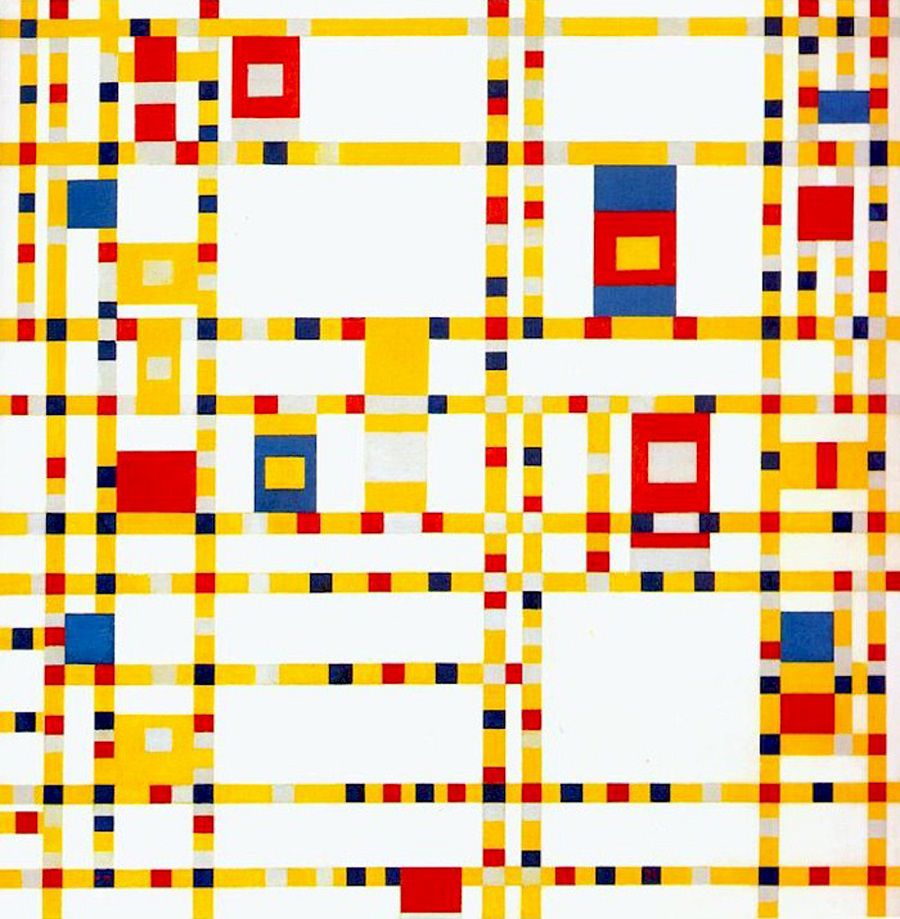

When I was younger, I was obsessed with the work of Piet Mondrian. I had posters of his work hung in my room and I would stare at them for hours, trying to figure how he did it. Why does his work seem so perfectly balanced and visually harmonic? Why did he work with only primary colors? Why did I love those colors together so much?

Just a little color theory 101: primary colors are the parents of the color wheel: red, blue, and yellow. When combined, they create secondary colors: green, purple, orange. Primaries can’t be made from mixing other colors.

Color theory has always been the most fascinating subject to me. A few years ago I was in the program Taking Things Apart, which combined microbiology with visual arts. It actually changed my life in a lot of ways, because I never fully realized how much science informs art and creativity. During one quarter of this class, we studied visual processing and the biology of how we see, and then in the drawing studio learned how to see. Vision “involves the nearly simultaneous interaction of the two eyes and the brain through a network of neurons, receptors, and other specialized cells” (2). When processing color, we perceive the wavelengths of color that are being reflected on that objects surface. Thus, red is not “in” an apple. The surface of the apple is reflecting the wavelengths we see as red and absorbing all the rest. An object appears white when it reflects all wavelengths and black when it absorbs them all. “The human eye can perceive very slight differences in color and is believed to be capable of distinguishing between 8 to 12 million individual shades. Yet, most colors contain some proportion of all wavelengths in the visible spectrum. What really varies from color to color is the distribution of those wavelengths” (3).

During my exploration of earth-based pigments this quarter, I’ve been able to marvel at the science and geology of color. It’s amazing that some colors, like red, are everywhere in nature– from berries and dyes, to tropical bird feathers, to red-earthen clay buried deep under our feet. Whereas green, the most ubiquitous color in nature, is much more rare to find in pure pigment– green is usually found in a more blue or more yellow form. (And, for this same reason is why US money is printed with an anti-counterfeit patented green ink).

Food, plants, minerals: Is it alive? Does it grow? Or does it come from the ground? In just 20 questions, we can (most likely) pinpoint anything on this planet. Yet in a world where we get to experience “8 to 12 million different shades” of color (and the fact that those colors do indeed exist), the research behind what color is and where it comes from is a lifetime’s work. Which is why it’s important to start where you are.

Color– from how we see it to how it occurs in nature– has everything to do with evolution. From an evolutionary perspective, color can tell an entire story about a place and how humans evolved and adapted to the region. “In the natural world— where the color of an ochre might depend on the exact place where it was mined, or where an indigo dye could be dozens of different shades, depending on the dipping time, the alkalinity and even the sunniness of the day— making colors has traditionally been an imprecise although often highly symbolic activity” (Finlay 6080).Our relationship to color holds a historical, cultural, and psychological significance that is begging to be understood. However (all science aside) I’ve come to the realization that the significance of color is really in the eyes of the beholder.

Which brings me back to Mondrian.

Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie, 1943

Mondrian aimed to create a “universal aesthetic language” in his paintings. He “believed that art reflected the underlying spirituality of nature. He simplified the subjects of his paintings down to the most basic elements, in order to reveal the essence of the mystical energy in the balance of forces that governed nature and the universe” (4) Although his paintings aren’t reminiscent of the natural world at all, Mondrian seems to reveal something pure and harmonic that is similar to something you could only find within nature. I think it has something to do with his use of primary colors– those parents of the color wheel that can only be created from themselves.

Every artist knows you just need these 3 colors in their paintbox to create a multitude of other colors. As a way to honor the primaries, I have researched their availability in Indonesia in plant and/or mineral form.

Plant Source: Indigo

Indigo is a natural dye extracted from several species of the plant. Most natural indigo is obtained from the genus Indigofera, which are native to the tropics. “For nearly 5,000 years, in almost every culture on earth, indigo plants of many species have been prized for the intensely beautiful blue pigment they impart. Japanese indigo, or Polygonum tinctorium, is a species of indigo that grows well as an annual crop in temperate North America” (5). Indigo is one of the oldest dye plants, used in ancient Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, Asian and African civilizations. India is believed to be the oldest center of indigo dyeing in the Old World, supplying indigo to Europe as early as the Greco-Roman era. In ancient times only royalty could afford to wear indigo-dyed clothing; some robes were literally worth their weight in gold.

“Demand for indigo dramatically increased during the industrial revolution, in part due to the popularity of Levi Strauss’s blue denim jeans. The natural extraction process was expensive and could not produce the mass quantities required for the burgeoning garment industry. So chemists began searching for synthetic methods of producing the dye. In 1883 Adolf von Baeyer (of Baeyer aspirin) researched indigo’s chemical structure. He found that he could treat omega-bromoacetanilide with an alkali (a substance that is high in pH) to produce oxindole. Later, based on this observation, K. Heumann identified a synthesis pathway to produce indigo. Within 14 years their work resulted in the first commercial production of the synthetic dye. In 1905 Baeyer was awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery” (6).

However, there are costs to consider for this Nobel-prize-winning discovery. The town of Xintang in China, known as the “denim capital of the world”, is poisoning major rivers with synthetic dye, bleach, and denim scraps (7). This issue is not uncommon in this small island of Bali, where high import costs and cheap alternatives are a reality for food and textile production.

Tjok Agung is known as the Indigo Guru of Bali and has made strides to form sustainable indigo production in Bali. “Deeply concerned about environmental issues and sustainable livelihoods in Pejeng, [Agung has] already [been] involved in several community projects. Growing indigo offers an opportunity for village farmers to benefit from a new crop while nourishing the rice fields.

“The rice fields should rest or be sown in a different crop every two or three harvest cycles, but that hasn’t been done here for a long time,” he points out. “I’m encouraging farmers on my family’s land to plant indigo between rice crops. Not only can they sell the indigo to me, but the fields benefit from the extra nitrogen since some indigo plants are legumes.

“The chemistry of indigo dyeing is very complex and takes years to learn. Traditionally indigo is fermented before use, but I’ve developed another system where indigo leaves are composted for a month with microbes made from locally available materials” (8)

Fibershed is another project that focuses on sustainable indigo production out of the Pacific Northwest. The Indigo Project uses the same fermentation technique of composted indigo leaves– called sukumo.

I personally can not wait to get my hands dirty in an indigo vat. Once unveiled, this plant has so much to offer itself, and sustainable harvesting and preserving practices are becoming more common, in Bali and beyond.

Plant Source: Achiote

“Bixa orellana is a shrub or small tree originating from the tropical region of the Americas. North, Central and South American natives originally used the seeds to make red body paint and lipstick. For this reason, the achiote is sometimes called the lipstick tree” (9)

In January, I received a brilliant gift from my boyfriends mom from Columbia, a book called Color Amazonia by Susana Mejia. It was pure coincidence that she gifted me this book when about to embark on my quest for place-based color. During this time I spent many hours in bed (post-surgery) fumbling through the pages thinking: my god I’ve got to get to the Amazon. I soon realized that many of the plant species listed in this book, given the tropical climate, also grow here in Bali. Achiote is one of these plants. In fact, there is a tree growing on Green School campus, and luck would have it that it is currently in bloom!

image of achiote tree at Green School

To further prove my equator theory, a Brazilian friend recently brought back some “urucum” for me to experiment with natural dyes. I wasn’t exactly sure what she was talking about, but sure enough she showed up with a bag of achiote from Brazil last week and told me that it had been in full-bloom there as well. She explained that many native Brazilian tribes use this as a body paint.

Because achiote doesn’t grow rapidly in Bali, the uses aren’t widespread. However I have been told that many local kids like to use it as a temporary hair dye. I’ve recently been using it in my eco-prints and the seeds create a nice, subtle red dye that would be stunning in massive quantities.

Other sources of red:

- Baccaurea racemosa or ramiflora- Burmese grape- Kepundung (Bahasa)–A medium-size tree found in the higher parts of Bali that produces abundant bunches of juicy, spherical, potato-colored fruits, about 2.5 cm. in diameter, very popular as snacks. Oval leaves, up to 7 x 18 cm. The bark, roots and wood are used to produce a brown-red dye.

- Mangosteen- Mangostana garcinia- Skins of the fruit can be boiled and mixed with a mordant to fix the dye onto paper or fabric. Not lightfast. Turns out more of a purple than red.

- Madder root– Rubia. The most common of red dyes in SE Asia. Mixed with Soapnut to fix (see previous post from field trip to Sanur)

- Brazilwood- Caesalpinia tree- “When the brownish powder of brazilwood is wet it turns reddish. When steeped in a solution of lye it colors the liquid deep, purplish red, and hot solutions of alum extract the color from the wood in the form of an orange-red liquor” (x)

- Red ochre

Plant Source: Turmeric

Turmeric is an “herbaceous plant that grows up to one meter in height. It’s dark-green elongated leaves stem from the base of the plant. The flowers, white to light yellow, are grouped on a circular pin that originates from the center of the plant. Recognized for it’s underground root system (rhizome), brown on the outside and intense yellow-orange on the inside, similar to ginger

“Uses: Curcuma has been used in India for 4,000 years as a traditional substance for dyeing fabric, painting the body, and medicinal purposes. Currently it is used in cooking due to its color and flavor– notable for giving curry its color– It has a pungent, spicy and aromatic smell. As medicine it has been used to treat heartburn, arthritis, and as an anti-inflammatory” (Mejia 163).

Turmeric is probably one of the most common household dyes. In India, there is even an ancient belief that using raw materials in textiles works for healing benefits as well. “Ayurveda fabrics work like this: the skin is a large, and highly porous part of the body. Anything it comes into contact with for an extended period of time will be absorbed and can potentially affect one’s health. That’s why it’s not such a great idea to wear clothes that have been treated with harsh dyes or other chemicals- your skin will eat those up! However, if one wears fabric that is imbued with a healthy substance (such as that energy-boosting cinnamon [,or in this case turmeric]) it will be absorbed and affect the body’s physiology in a positive way” (10).

I have to agree that I feel energized when I use, feel, taste, and even see turmeric. In Bali, turmeric juice is used as “jamu” (meaning medicine), a potent drink combined with tamarind, honey, and ginger. In fact, after I used some of the turmeric pictured above as paint, it went immediately on my stove top as tea. It is truly one of those multi-purposeful and powerful roots that I am happy is so abundant here on the equator.

Other sources of yellow:

- Aegle marmelos- Indian Bael- maja batuh (Bahasa Indonesia)– From the fruit household glue, dye, tanning agent and various medicines can be produced. Bark, leaves and roots have a number of medicinal uses and the bark can also be used as fish poison. Bark yields a yellow dye when heated. The tree is sacred in Hindu religion.

- Jackfruit bark– yellow dye, latex used as glue and cement. There is 3.3% tannin in the bark. When boiled with alum, wood chips, or sawdust, it yields a dye that is commonly used to give the characteristic color to the robes of Buddhist priests and in dying silk.

- Marigold flowers. “To dye with fresh or dried marigold flowers, cover them with warm water and let them soak overnight but not more than two days. Mash the flowers in the pot to break their fibers. Bring the water to a boil and turn it down to simmer for an hour. Strain off the flowers and your dye bath is ready.” (x)

- Yellow ochre. Was this the earth pigment that we found in Toraja? I need a geologist, stat!

primary painting with natural brushes. source: danceypantsd instagram

How to conclude one of my last Taste of Bali research posts? I simply can not. Best thing for me to do is to take this knowledge, share it, and then get out of this here chair and start making stuff!

BOOK REFERENCES:

- Finlay, Victoria (2007-12-18). Color: A Natural History of the Palette (Kindle Locations 272-274). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

- Mejía, Susana, Jairo Upegui, and Viviana Palacio. Color Amazonia. Mendellin: Mesa Editores, 2013. Print.

Other related articles that I thought were interesting:

Be First to Comment