I must be honest about something. I’ve been here exactly 4 months and I feel like I am just starting to like Indonesian food. Kind of.

At home, I am used to eating fresh, simple food with only a couple of ingredients. And by simple, I could even mean a little boring. A typical lunch for me would be a combo of 2-3 steamed veggies with some local meat for protein. This worked really well for me because I love knowing where my food comes from. I am incredibly lucky to be working at a place that shares this value.

Like I mentioned before, Student Village has 3 values when it comes to our buying and preparing our food: local, organic, and whole. Unfortunately in Bali, these things don”t even come close to the radar of traditional, everyday cuisine. Almost every single dish is fried in cooking oil that, on average, is being reused about 250 times. I learned this staggering statistic from one of the social enterprises at Green School called the BioBus, a sustainable transportation system that makes biodiesel out of used cooking oil. BioBus buys the cooking oil from local warungs that have bought it from other warungs that have bought it from slightly nicer warungs, and so on. I suddenly wish this post was about BioBus… it is such a cool enterprise. They take the glycerin from the biodiesel manufacturing and make earth-friendly soap out of it. Not to mention… this is a student-run organisation that started earlier this year and they are currently at the COP21 in Paris right now to spread word on this idea. It’s amazing! But back to what I was talking about…

The palm oil use in Bali is ubiquitous. According to Wikipedia, “Palm oil production is important to the economy of Indonesia as the country is the world’s biggest producer and consumer of the commodity, providing about half the world supply. Oil palm plantations stretch across 6 million hectares (roughly twice the size of Belgium). The country plans by 2015 to add 4 million additional hectares towards oil palm biofuel production.” This exact statistic is coming true as devastating forest fires are sweeping through Indonesia due to the slash and burn techniques used to clear land for palm oil production. The fires have destroyed land, released massive amounts of carbon, have affected hundreds of thousands of people with respiratory infections, and have threatened 1/3 of the worlds orangutang population.

Regardless of the environmental and public health crisis currently happening, the Balinese still use palm oil daily for nearly every single dish. The reasons behind this would be a very interesting and important topic of research. Green School and SV are seen by locals as weird for having “palm oil free” kitchens. Even the kitchen staff at SV shake their heads in disagreement/disappointment with having to use coconut oil instead of palm oil. It’s a difficult topic to research and get behind the facts because the billion-dollar palm oil companies are constantly endorsing corrupt information about their products.

And so, it’s impossible to study Indonesian terroir without first addressing the cultural use of palm oil. I have a few questions regarding this:

How does palm oil use affect the “racines, or roots, a person’s history with a certain place?” (Trubek)

In The Taste of Place, Trubek says that “local taste, or goût du terroir, is often evoked when an individual wants to remember an experience, explain a memory, or express a sense of identity”. How have some dishes evolved over the past 20 years with the growing expansion of palm oil production? How has Balinese goût du terroir been preserved?

If “the moment when the earth travels to the mouth is a time of reckoning with local memory and identity”, how does the corruption behind palm oil production in Indonesia affect the lives and pallettes of the locals?

These questions are pretty heavy, and I don’t have the answers. For this case study, I decided to team up with Ayu, the head of the kitchen at SV, to teach me about some of the traditional dishes here in Bali. I asked her to tell me about Balinese staples that hold the true taste of Bali.

The staff usually prepares at least 1-2 Indonesian dinners a week. I am constantly amazed at the amount of preparation that goes into these dishes. They are complex meals that take 6+ hours to prepare. I have so much gratitude for Ayu and Kadek who work so hard to feed us. They are amazing! This is why these are the rules I made for the kitchen:

Here are a few noteworthy dishes in Bali:

SOTO AYAM (my favorite)

Soto ayam (soto=soup, ayam=chicken) is a chicken noodle soup originated in Java, with a delicious broth base spiced with coriander, cumin, shallots, garlic, turmeric, galangal, ginger and lime. It had shredded chicken, sliced tomatoes, boiled egg, sliced cabbage, bean sprouts, onions, and grated coconut on top. Sambal goes on top, but not for the weak!

note: Galangal is a member of the ginger family. It is similar but larger. It has a sweet, woody smell.

img source: cooking.nytimes.com

BUBUR

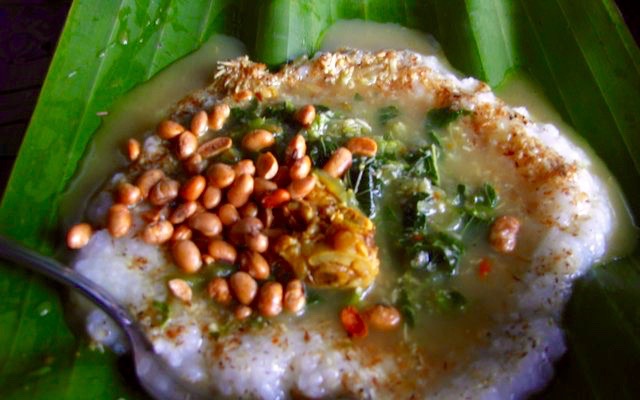

‘Bubur’ is rice porridge. It’s very similar to American Cream of Wheat, a wet couscous or a rice version of oatmeal. I’ve only seen this served at Green School for breakfast. I believe that bubur is also a comfort food for anyone who’s sick with the flu or stomach ache.

The server first fills their banana leaf with a heaping portion of bubur. On top you can put spiced chicken and garnishes. Every person makes it slightly different. The most common ingredients are whole peanuts, sauteed greens, shallots, roasted onions or garlic, and shredded coconut.

image of a traditional bubur breakfast at Green School

GADO GADO

Gado-gado is a basically a vegetable salad covered with peanut sauce. There are many regional variations, the most significant of which is whether or not the vegetables are cooked or raw. I’ve had gado-gado as either a light main course or just an appetizer. What’s interesting about this dish is the presentation is always different, the only indicator that it’s “gado-gado” is the peanut sauce.

Image of Gado-gado from Seniman Coffee in Ubud, Bali. I thought I had accidentally ordered sushi, but then I saw the peanut sauce.

NASI GORENG

Nasi=rice

Goreng=fried

Also called “Nasty Goreng” by one of my boarding students, I have to object that there is nothing nasty about nasi goreng. Considered Indonesia’s national dish, this take on Asian fried rice is traditionally made with sweet, thick soy sauce called kecap (ketchup… a product that is not allowed in SV kitchen) and garnished with acar, pickled cucumber and carrots.

image of Nasi Goreng courtesy of farmhousehome.com.au

SATAY

The Balinese LOVE satay. I see satay as one of Bali’s most humble foods. I think this is because on every street you will find small vendors with these tiny grills fanning their satay. Satay consists of skewers of grilled meat and then served with anything really. The skewers themselves are usually made from the midrib of the coconut palm or from bamboo. They are usually chicken, although pork is common as well (remember, Bali is the only Hindu island in Indonesia!). They are served with spicy peanut sauce, rice cakes or mixed slivers of cucumber and onion.

image of an Ibu grilling satay on the street. Sept 2015.

LAWAR

This dish is very common at Student Village, and a lot of work and time goes into it. It’s composed of finely chopped combinations of various ingredients such as green beans, green papaya, shallots, pork meat and pork skin, eggs and coconut. It’s an Indonesian classic. Ayu told me that in old tradition, blood from the meat is added to enhance the dishes flavor. Yummy!

image source: pegipegi.bisnisonlinez.com

References:

Trubek, Amy B. (2008-05-05). The Taste of Place: A Cultural Journey into Terroir (California Studies in Food and Culture) (p. 51). University of California Press. Kindle Edition.

Be First to Comment