Petrochelidon pyrrhonota

Studied by: Anne de Marcken, spring 2012

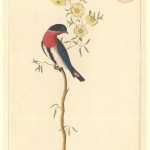

“Cliff Swallow in Flight.” Don DeBold. Flickr. April 28, 2009.

I wanted to study an animal that shares my urban habitat. I wanted to challenge the notion that nature is somewhere else – that human environments are separate and different from the “natural” environments where other animals live. Across the street, there is a tall building where cliff swallows nest in the eaves.

Observation notes, 7:15am, April 21, 2012: I hear swallows! The “chat. chat” call. It takes me a minute to see them. Two. Flying. Not sure at first. But they swoop and reverse. V-shaped wings. They have returned!

Also, I was interested in studying an animal about which I already had a preconceived idea. Could I overcome this and begin to see the animal as itself? As a child, I raised dozens of cliff swallows as a wildlife care volunteer. For whatever reason, I had a touch with swallows, which are difficult to raise because they are insectivores, because it is necessary to reproduce their enclosed nest structure with its small opening, and because of their unique personality.

Animal Book entry: They were not like the jays and blackbirds – or any of the other songbirds we took care of. They don’t like to sit on you, to cuddle…and they are not curious about humans and human things. They are intense, focused, aloof. I liked them best even though – or perhaps because – they never seemed to care much about me one way or another. They seemed more wild – even in our kitchen – than the other nestlings.

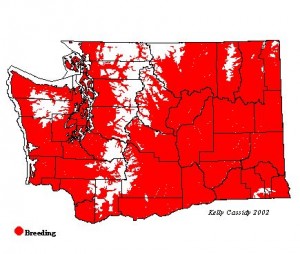

Cliff swallows, like crows, gulls and raccoons (see: Ariety’s raccoon and Tyler’s raccoon), have adapted well to human interventions in the environment. Their range has expanded significantly and their nesting and winter colonies are more often found on buildings, bridges, and overpasses than actual cliffs.

Observation notes, 7:15am, April 20, 2012: Two birds in a pair, approximately 60′ up over Columbia and 9th. Fast turns, trading tacks.

Observation notes, 7:15am, April 20, 2012: Two birds in a pair, approximately 60′ up over Columbia and 9th. Fast turns, trading tacks.

Cliff swallow migration map, United State Geological Survey web site, “Migration of Birds,” and North American and Washington State range maps, birdweb.org, “Cliff Swallow.”

Humans pose some threat to swallows: the owner of the building across the street knocked down last year’s nests, presumably because they seemed in some way to defile its angles and engineered surfaces with their own more organic architecture. Cliff swallows build their nests out of mud that they carry one beak-ful at a time from as far away as ten miles. They line their nests with grasses, feathers, fur, and other soft materials.

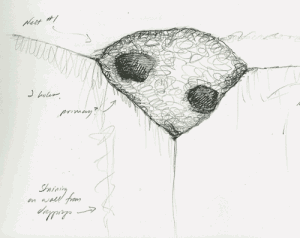

Observation notes, 7:30am, April 20, 2012: Nest interest! Two birds attend nest #1 and #3. They touch in without landing, flutter, loop back out. Now one bird lands on #1, which is the most intact. Stays for 10-20 seconds.

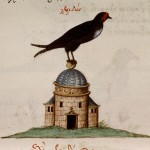

Still frame from a 1947 16mm silent film of the “installation” of a Cliff Swallow “study case” – preparation and taxidermy of dead birds for display at the Field Museum of Natural History. To view the 7-minute film, which also shows curator, John R. Millar building swallow “nests” using a cake decorator, visit archive.org.

Still frame from a 1947 16mm silent film of the “installation” of a Cliff Swallow “study case” – preparation and taxidermy of dead birds for display at the Field Museum of Natural History. To view the 7-minute film, which also shows curator, John R. Millar building swallow “nests” using a cake decorator, visit archive.org.

Observation notes, 8:00am, April 28, 2012: No swallows – but starlings, sparrows, a few crows, and gulls on the grange building on Capitol. I wonder if the swallows return to their own old nests, or will occupy any old nest. Do they consider it a risk to rebuild at a site that has been disturbed during the winter season?

Observation Site: Columbia & 10th

Cliff Swallows seem to have unerring sense when it comes to choosing a nest location. Very few birds die because of unstable nests or because of vulnerability to predators. So will the swallows consider this an unsafe nesting location since the nests were disturbed over the winter? As my observations continued, I remained anxious over the inconsistent attention to the nest sites. As the weeks passed and I would have expected to see progress, only nest sites #1 and #3 were restored. My sense was that the birds were not committed to these nests.

Animal Book entry: I feel incapable of turning the animal into a character – my resistance is strong. I hate making it cute or silly. I am inclined to work with the skeleton because it is already stripped of life.

Two collaborative zoetrope animations with Ruth Hayes, who studied the Townsend’s Chipmunk. Click to view.

Observation notes, 7:00am, April 30, 2012: No birds. Light rain. I think: the rain is good for nest-building because of the mud it creates, but bad for hunting. How long can swallows go without a good day of hunting?

From what I read, cold weather is the greatest threat to cliff swallow populations. Late, prolonged cold snaps can cause significant loss of life in colonies: some reports document 90% mortality due to lack of adequate food…it isn’t the cold temperatures per se, but rather the effect of cold on insect populations. Their diet is made up almost entirely of flying insects, though they are known to occasionally eat berries. (citations)

Animal Book entry: When we were raising them, we fed the hatchlings “bug butter,” a mash of Gerber’s pureed beef baby food and ground up meal worms. As they matured, we would cut up meal worms into “bite-sized” pieces and feed them to the nestlings with tweezers. As they got older and more ready for flight, they could handle whole meal worms. I remember once when a nestling was fading because it refused to eat, I decided to try it on flies. It liked those better. I spent hours outside with the fly-swatter collecting enough bodies to keep the bird fed. Eventually it was willing to eat meal worms. Would I do this now? Choose the bird over the bug? I think so.

Observation notes, 7:15am, May 5, 2012: Lots of activity around nest #1. At least two birds come and go from the nest and the lower hole has been patched.

Observation notes, 7:15am, May 5, 2012: Lots of activity around nest #1. At least two birds come and go from the nest and the lower hole has been patched.

Observation notes, 3:30pm, May 6, 2012: No sign of the #1 pair, now how I will refer to the birds I observe tending nest site #1 even though I cannot be sure it is always the same birds or even that it is only two. I have learned that cliff swallows sometimes – not infrequently – nest in threes!

Observation notes, 4:00pm, May 6, 2012: Several swallows arrive. Some check in at nest sites #1, #3 and #4. “Touch and go” pattern. Seven total. “Circling flutter/glide” for about five minutes, then disperse in various directions. None land at any nest sites. Lots of “conversational chats.”

Animal Book entry: I find swallows in a Navajo creation myth, Dine Bahane’, “Story of the People”: The insect people were banished from the “first world” because of their sexual transgressions. They went to the “second world,” the world of the swallow people. This was a blue world. Soon the insect people got themselves in trouble again and were kicked out by the Swallow Chief. They crawled out through a small hole at the top of the world.

I picture the hole in the blue world. A hole in the sky. We are the insect people.

*It is not a cliff swallow—the throat markings are wrong.

Every day the swallows do not return, I take it as a sign. Nothing can be counted on. Even their absence is about me.

In an effort to make a blue as blue as the blue world, I make a page of sky swatches. Panes. It is pleasing to me, but a failure. Water not air. Surface not void.

I call Mum and ask if she has any photographs of me with the swallows. The next morning: Her hands (not mine) cupping a bird*. I calculate that she was my age when the photograph must have been taken—her hands then the age of my hands now. I am more alert than ever for corroborating evidence of our difference.

Cliff swallow is the only member of the family without a forked tail.

I realize: I picture my swallows with “swallow tails”—even after an hour of observing them in flight. As soon as I look away from the actual birds, I replace them with a composite facsimile that is somehow emblematically true, though it is false.

This is how it goes: the bird in the imagination is worth two in the sky. I will not let it go.

(simulacrum—sim-u-la-crum—la, la, la, la, la)

Observation notes, 9:00am, May 13, 2012: Nest #1 is still quiet. No sign of life, inside or out. Does this mean they are setting? Or have they, as feared, decided to settle elsewhere? Nest #3, on the other hand, is consistently occupied and I am worried: the nest does not seem properly constructed. I can see into it clearly. Surely this means the opening is too large – too wide – too easy for hatchlings to fall out or be attacked by marauders.

It takes a 12-13 days for eggs to hatch after setting. Cliff swallows my have two broods in one season. They sometimes move their eggs to neighboring nests – carrying them in their beaks!

Swallows are sometimes preyed on by kestrels and other small hawks. Rodents and snakes may enter vulnerable nests and eat either young birds or eggs. In one year-long study of a large cliff swallow colony in Kentucky, scientists reported that a particular grackle had learned to wait on the ground to attack swallows landing to collect mud for their nests.

Observation Notes, 6:30am, June 3, 2012: Babies in nest #1! When did they hatch? In the night? This morning? #1 pair comes and goes from their nest at 4-5-minute intervals. They approach (separately), enter the nest, stay inside for about 30 seconds to 1 minute, then leave in a hurry – dropping away and into direct flight – no circling. Nest #2: two adults in the nest. Are the setting? Will they have hatchlings soon, too? I remember, now, that another difficulty with raising swallows in captivity is that they need to eat more frequently than other baby birds: 5-10-minute intervals. The swallows will now by extremely busy! The hatchlings will fledge in 3-4 weeks.