I selected the chicken for my animal of interest because the chicken is a domesticated animal, meaning they have a co-dependent relationship with humans. This has a major impact on the way chickens live their lives and I thought I could observe some interesting social behavior amongst the chickens.

Natural History Information

The Chicken

Classification

Order- Galliformes

The Galliformes are large, mostly flightless birds that feed on the ground. Known as land fowl, the Galliformes are things like pheasants, turkeys, peacocks, quail, junglefowl.

Family- Phasianidae

Phasianidae includes pheasants, quail, junglefowl and partridges. As it’s such a broad classification it contains the sub-family Phasianinae, which is where chickens are located.

Genus- Gallus

Gallus is the junglefowl arm of the Phasianidae family. Junglefowl birds can barely fly, even less so than pheasants. The Red Junglefowl are the last known degree of separation between domesticated and wild chickens and it is believed that human interaction with Red Junglefowl lead to the first domesticated chickens.

Chickens vs. Junglefowl

The Red Junglefowl, native to Southeast Asia, is known as Gallus gallus. The domesticated chicken is known as Gallus gallus domesticus. There is a big difference between the implications of these two words because G. Gallus refers to one species of wild animal that is believed to be the parent of the common domesticated chicken. G. Gallus Domesticus refers to all domesticated chickens, which is a very broad category that probably lends itself from many species of wild junglefowl. In general though, domesticated species will never fit into a phylogenetic chart like wild species will.

Physical Description

Chickens are a variety of sizes but are usually between 12-16 inches tall. The species experiences sexual dimorphism, with males being much larger than females. Their knees bend backwards, like any bird, but they are too stout with too short of a neck to be suited for running fast.

Vocalization

Chickens are extremely vocal creatures and are constantly making noise. Hens make a warbling chirping sound that is called clucking. Hens cluck when they’re excited, which can be when they find food, when someone’s coming, basically whenever anything happens because chickens are very easily excited.

Roosters are very well known for their vocalization. Roosters make a loud crow with their vocal chords that is actually very melodic. I don’t mean melodic in the sense it’s nice to hear I mean the call follows a melody. Everyone is familiar with “cook-a-doodle-doo!” and while it sounds simple it is a complex bird call.

Habitat

While chickens are related most commonly to red junglefowl, which live in Southeast Asia, because of domestication by humans they can be found all over the world. Almost every culture in the world eats chicken and chicken eggs if they are able to produce them.

Behavior

Chickens are similar to any other domestic animal in that their biggest activity is eating. They spend the vast majority of their time pecking at feed left out by the farmer, and also digging for worms. Every chicken coop has one, and only one, rooster. The rooster breeds with all of the hens in the coop. One interesting dynamic between roosters and hens is while feeding the rooster will call the hens over to eat.

The hens that I observed didn’t have a rooster, as it’s illegal to keep a rooster within city limits. I discovered that the four hens remained in groups of two at all times. Two of the chickens were striped black and white and two were a solid brown color. I observed that the chickens of opposite color patterns paired up with each other, and in both cases the black and white chicken was dominant to the brown chicken.

Evolution

Chickens’ closest relative is the Red Junglefowl of Southeast Asia. It is believed that the chicken was originally domesticated in Southeast Asia around 6000 B.C. The chicken made its debut in Europe around 3000 B.C.

A favorable trait of chickens for domestication is their flightlessness. Their inability to fly gives chickens a very small area that they can travel, making it easier for chickens to get close to humans and develop co-dependent relationships with humans. Also, flightlessness makes chickens capable of getting fatter and tastier than other birds. Chickens lay eggs very often, more often now that we’ve bred them for that purpose.

Works Cited

Eriksson J, Larson G, Gunnarsson U, Bed’hom B, Tixier-Boichard M, et al. (2008)Identification of the Yellow Skin Gene Reveals a Hybrid Origin of the Domestic Chicken.PLoS Genet January 23, 2008

Fumihito, A; Miyake, T; Sumi, S; Takada, M; Ohno, S; Kondo, N (December 20, 1994), “One subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus gallus) suffices as the matriarchic ancestor of all domestic breeds”, PNAS 91 (26): 12505–12509

Zeder et al (2006) “Documenting domestication: the intersection of genetics and archaeology,” Trends in Genetics, vol 22, number 3, pp. 139-155.

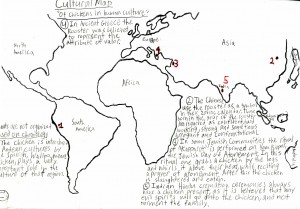

Here’s a map of some noteworthy cultural landmarks from around the world that feature the chicken.

Cultural Research

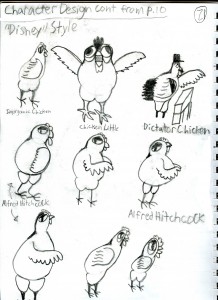

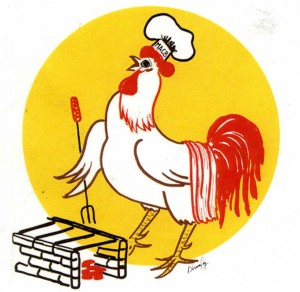

These are some of the drawings I did this quarter.

Direct Observation/Creative Writing

Manchester Chicken Broil. Manchester Chicken Broil, Nov. 17, 2011. Web. Accessed April 13th, 2012.

Ekphrastic writing

He’s laughing, throwing back his head as though he’s lining out. His whole body is like a bow, drawing back, building up, then firing an arrow tipped with his smiling eyes; his jovial laugh is the whistling in the feathers. Such contentedness as he cooks his own kind, we can all be such cocks sometimes.

The rooster stokes the coals with a long two pronged fork clasped in the feathers of his right wing. A white chef’s hat adorns his head, the excess skin of his waddle tucked into it to keep it from falling off. The most elaborate vestige of his human appeasement is the white cloth draped across his back, which he cannot use himself and was certainly adorned upon him by his owner. He wears it as a badge of pride. Looking closely at our friend we see him as a shape shifter, a chameleon, who has so brilliantly fashioned himself, or been fashioned rather, into a man. When we take a step back, however, we see that he’s just another chicken at a chicken broil and won’t end up as anything besides heartburn.

Between Me and You

You tussle and fight,

Shoving and squawking,

Just so you can stand atop a hay bale stage,

Elevated, and performing just for me.

Between us sits space,

Though not a whole lot,

And a chain link fence,

But it’s flimsy and short.

There’s another space between us,

That you can’t see with your eyes,

Every thought that can’t be spoken,

Every utterance that sounds garbled and alien.

So here I stand,

Or sit rather,

With every luxurious amenity,

Shoes on my feet,

Shirt on my back,

And with pencil and paper,

And the written word,

And the prose that my teachers taught me,

And those lines and perspectives too,

I wonder if there’s anything bigger than me.

Watching me,

Watching you.

Cultural Research Works Cited

The Chicken in Andean History and Myth: The Quechua Concept of Wallpa. Linda J. Seligmann Ethnohistory , Vol. 34, No. 2 (Spring, 1987), pp. 139-170. Published by: Duke University Press. URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/482251. Web. Accessed May 13th, 2012.

No Author. “News.” Groups Protest Use Of Chickens In Hasidic Jewish Ritual Called Kaporos « CBS New York. 7 Oct. 2011. Web. 13 May 2012. <http://newyork.cbslocal.com/2011/10/07/groups-protest-use-of-chickens-in-hasidic-jewish-ritual-called-kaporos/>.

“Indo-European and Asian Origins for Chilean and Pacific Chickens Revealed by MtDNA.” Ed. Joyce Marcus. 29 Feb. 2008. Web. 13 May 2012. <http://www.pnas.org/content/105/30/10308>.

Robert Wessing. Symbolic Animals in the Land between the Waters: Markers of Place and Transition. Asian Folklore Studies , Vol. 65, No. 2 (2006), pp. 205-239. Published by: Nanzan University. Article Stable URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/30030399

Human Sacrifice in Bali: Sources, Notes, and Commentary. Alfons van der Kraan. Indonesia, No. 40 (Oct., 1985), pp. 89-121. Published by: Southeast Asia Program Publications at Cornell University. Article Stable URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/3350877

Shlomo Deshen. The Kol Nidre Enigma: An Anthropological View of the Day of Atonement Liturgy. Ethnology , Vol. 18, No. 2 (Apr., 1979), pp. 121-133. Published by: University of Pittsburgh- Of the Commonwealth System of Higher Education. Article Stable URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/3773286

Michael D. Swartz. Like the Ministering Angels: Ritual and Purity in Early Jewish Mysticism and Magic. AJS Review , Vol. 19, No. 2 (1994), pp. 135-167. Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Association for Jewish Studies. Web. URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/1486621

Ellsworth Huntington. The Distribution of Domestic Animals. Economic Geography , Vol. 1, No. 2 (Jul., 1925), pp. 143-172. Published by: Clark University. URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/140908

Scandalizing the Goddess at Kodungallur. M. J. Gentes. Asian Folklore Studies , Vol. 51, No. 2 (1992), pp. 295-322. Published by: Nanzan University. URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/1178336

Janeen Arnold Costa. Systems Integration and Attitudes toward Greek Rural Life: A Case Study. Anthropological Quarterly , Vol. 61, No. 2 (Apr., 1988), pp. 73-90. Published by: The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/3317158

Dennis R. Uit de Weerd, Dennis Schneider and Edmund Gittenberger. The Provenance of the Greek Land Snail Species Isabellaria pharsalica: Molecular Evidence of Recent Passive Long-Distance Dispersal. Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 32, No. 9 (Sep., 2005), pp. 1571-1581. Published by: Blackwell Publishing. URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/3566328

J. Ingersoll. Fatalism in Village Thailand. Anthropological Quarterly , Vol. 39, No. 3, Fatalism in Asia: Old Myths and New Realities (Special Issue) (Jul., 1966), pp. 200-225 Published by: The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research URL: http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/3316805