Panthera tigris sumatrae

Observed at Point Defiance Zoo

Introduction

Introduction

The Sumatran Tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) is one of nine subspecies of tiger (Panthera tigris) and is only found in the wild on the island of Sumatra in western Indonesia. Out of these subspecies six live mainly on the continent of Asia (Bengal, Indochinese, Malayan, Siberian, Caspian, and South China tigers), while the Sumatran, Bali, and Javan tigers live on the islands of their name in Indonesia, or at least they did. As of 1979, the Bali, Caspian, and Javan tigers were all hunted to extinction after losing much of their habitat, leaving only six subspecies of tigers in the world, and Sumatran tigers the only survivor of three who lived in the Sunda Islands.

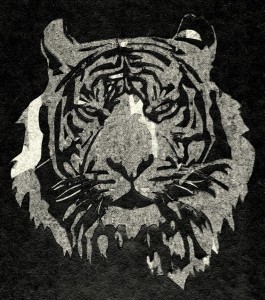

Sumatran tigers are known as one of the world’s most beautiful tigers, with their smaller bodies (they’re the smallest living tiger) , rich contrast of colors in their coat and a full almost lion-style mane, the word “tiger” is well represented through their visage. Sumatran Tigers have been classified as critically endangered by IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) in 2008, with a projected population of 441 to 679 individuals with a declining trend.

I have always had a great interest in cats, both domestic and wild, for their cunning, grace, and the generally high importance we perceive they hold themselves at. With the tiger’s incredible physical appearance (no other animal so striped and vibrant orange), mysterious history and influence on human culture, and the availability of four Sumatran tiger specimens nearby, I thought this would be a perfect animal other for my investigation. After some face time in with the tigers, and getting started on my research, I started to really understand how important education is to the preservation of these amazing cats, and how I could help with this by doing superior work in this program.

I trust that the more I learn about large wild endangered cats the more prepared I will be for my eventual independent study project abroad in Bolivia, where I will help rehabilitate and care for injured jungle cats while both observing them and the culture of South America.

All Image information is at the bottom of

this page in the Gallery. Click on an image

in the Gallery to see its Title and Source.

^ Malosi, Male Sumatran Tiger (focus)

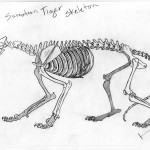

^ Visual Representations

^ Bima, Male Sumatran Tiger

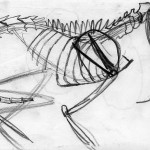

^ Domestic Cat and Sumatran Tiger

comparative structural studies.

Natural History

^ A tiger like skull unearthed from a 2.5 million year old rock, oldest known complete specimen related to modern big cats, closest to tigers.

As was said before, Sumatran tigers are only found in the wild on the island of Sumatra. They were in fact isolated from other tiger populations between 6,000 to 12,000 years ago as the rise in sea level separated the Pleistocene / Holocene border, forming today’s Indonesian islands. Since then they have evolved to survive in an island habitat and could possibly soon be considered an entirely new species, if kept from extinction; there is great interest in conservation of this specific subspecies of tiger in the world today. However, dwindling habitat and black market trading of “tiger goods” (pelts, claws, bones, teeth) make it paramount that people be made aware of how fast these animals are disappearing, with hundreds of cats killed every year around the world, preservation is at war with time to keep Sumatran tigers on the earth.

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Carnivora

Family: Felidae

Genus: Panthera

Species: Panthera tigris

Characteristics

The tigers of Sumatra are much smaller than mainland tigers (who average  450lbs and grow up to 11ft long) with males weighing anywhere from 220-310 pounds and measuring 87-96 inches in length from nose to tail, and females averaging 78 inches in length nose to tail and weighing between 180 and 240 pounds. Sumatran tigers’ small size is much better for jungle living, and they are still the kings on Sumatra even if they are dwarfed by some of their relatives. The second thing that one notices is the intensity of the orange and black fur, which has a much higher contrast on Sumatrans between the two groupings with a more dark reddish coloration in their orange coats than any other remaining tiger. Sumatran tigers have slender and plentiful stripes that tend to disintegrate into spots near the tips and on legs and feet. In the pictures below check out Malosi and Bima’s hind legs, and note the patterns that are apparent on Bima’s hind feet that Malosi does not have. Because no tiger shares the same stripes, the patterns can be used to identify tigers kept in zoos or ones being observed in the wild. Sumatrans are also the only tiger with a membrane between fingers that lets them swim faster and more effectively. This allows them to trap prey in water where it is less mobile, and then swim in, bite down, and drag it out.

450lbs and grow up to 11ft long) with males weighing anywhere from 220-310 pounds and measuring 87-96 inches in length from nose to tail, and females averaging 78 inches in length nose to tail and weighing between 180 and 240 pounds. Sumatran tigers’ small size is much better for jungle living, and they are still the kings on Sumatra even if they are dwarfed by some of their relatives. The second thing that one notices is the intensity of the orange and black fur, which has a much higher contrast on Sumatrans between the two groupings with a more dark reddish coloration in their orange coats than any other remaining tiger. Sumatran tigers have slender and plentiful stripes that tend to disintegrate into spots near the tips and on legs and feet. In the pictures below check out Malosi and Bima’s hind legs, and note the patterns that are apparent on Bima’s hind feet that Malosi does not have. Because no tiger shares the same stripes, the patterns can be used to identify tigers kept in zoos or ones being observed in the wild. Sumatrans are also the only tiger with a membrane between fingers that lets them swim faster and more effectively. This allows them to trap prey in water where it is less mobile, and then swim in, bite down, and drag it out.

Habitat

There are 3 requirements for a tiger habitat: Adequate Prey, Abundant Water, and Extensive cover. Sumatran tigers need forested areas with lots of cover in order to live and procreate, as well as savanna or highland landscapes for hunting. Caves in the Montane forests will often be commandeered for cover and so that any tiger cubs can be hidden safely while the mother is out hunting. With Sumatra’s agricultural growth, Sumatran tiger habitat will, unless preserved, continue to be fragmented and destroyed until there is not enough to sustain a population.

Diet

A dominant carnivorous predator, Sumatran tigers are “stalk” and “ambush” hunters, who rely on the element of surprise because in a flat out foot race most of its prey would escape. It is agreed their preferred diet is deer and wild boar, boar being easier to catch but more dangerous to fight. However, a hungry tiger will eat anything; dogs, mouse-deer, turtles, peacocks, jungle fowl, buffalo, seladang, benteng, locusts, spiders, mice, frogs and monkeys who stray from the trees for too long. Tigers are also known to eat humans (see “Man-Eaters” below). Because a healthy Sumatran tiger can eat up to a 40lbs of meat at a time, they need 15-30 square miles or more of territory to supply them with enough prey.

Predators

Because of its size and power the tiger has no natural predators in its native environment. Humans that hunt Sumatran tiger and habitat destruction (loss of prey) are the only threats to its survival.

Copulation and Procreation

Although tigers are solitary creatures they do come together for procreation. A Sumatran tiger becomes sexually mature between the ages of 3 and 5 years old and has an average wild life span of about 15-20 years. A tigress can remain fertile for up to 12 years of her life, and can mate and have cubs multiple times in her life. She starts by making loud vociferous announcements that draw male tigers to her, who then fight for the right to mate. Once there is a victor, the two tigers flirt with one another by chuffing, touching faces, and rolling around on the ground together. Mating lasts about 3 to 8 days, and in this time tigers can fornicate as many as 100 times. The male tiger splits off from the female, returning to his territory, while the tigress looks after the litter. The gestation period for Sumatran tigers is about 3-4 months, and they can give birth to up to 5 cubs, although 2 cubs is the average. The baby tigers drink milk for two months before they are introduced to meat, and after about 18 months of learning how, they start to hunt their own food and move off in search of their own territory.

Behavior

Sumatran tigers are solitary creatures who are not distinctively nocturnal because they go out during the day time and the night. My favorite behavior of the tiger is the lazy saunter they embody so well, head staying still in vertical space as the body moves up and down. They mark territory with spray and scratch marks on trees, as well as growls and roars of their presence and will fight any other tiger who enters their domain.

The most interesting behavior I read about was in Boogmaards book Frontiers of Fear where he described a man-eating tiger having left a half eaten corpse, that was then burred by other humans, only to return to the site of the meal and then follow the scent of the carcass, searching. “This habit of trying to find out where their kill has been taken is, I think, one of the most ghoulish things about man-eating tigers.”

Cultural History

Tigers represent strength and a fearsome nature all across the world, some award these tiger traits using the positive spin (a great rulers power from divinity, or the pure energy content of Esso’s gasoline) but sometimes these personality extremes are seen more negatively. In Buddhism the tiger is one of the Three Senseless Creatures representing anger alongside the monkey, who symbolizes greed, and the deer who signifies lovesickness. While the tiger would eat both the monkey and deer in its natural habitat, this does not improve his case of being seen as a blood-thirsty beast who has few emotions but those that are highly violent.

In I ndia tigers are symbols of royalty and divine power. In China they represent yang, or good, in constant battle with the dragon yin, or evil, and in Sumatra and the Sunda Islands they are believed to embody divine retribution, traditionally. The main thing that all cultures share when speaking of tigers is the killing and using of them, whether for medicinal purposes (tiger parts are used in a vast array of traditional medicines, with hundreds of cats being killed and having their parts sold on the black market even today (see left)), or to protect their livestock and families, or in some cases as a justice system. As early as 1609 there are recordings of “tiger rituals,” a special event in game or judgment

ndia tigers are symbols of royalty and divine power. In China they represent yang, or good, in constant battle with the dragon yin, or evil, and in Sumatra and the Sunda Islands they are believed to embody divine retribution, traditionally. The main thing that all cultures share when speaking of tigers is the killing and using of them, whether for medicinal purposes (tiger parts are used in a vast array of traditional medicines, with hundreds of cats being killed and having their parts sold on the black market even today (see left)), or to protect their livestock and families, or in some cases as a justice system. As early as 1609 there are recordings of “tiger rituals,” a special event in game or judgment including several tigers of leopards. For game many would capture live cats and kill them in front of a roaring crowd, but in the “tiger courts” groups of suspected criminals were put in an arena with a hungry beast, the first suspect killed was guilty of the crime.

including several tigers of leopards. For game many would capture live cats and kill them in front of a roaring crowd, but in the “tiger courts” groups of suspected criminals were put in an arena with a hungry beast, the first suspect killed was guilty of the crime.

Contemporary works start to utilize the plight of the tiger with its impending extinction as well as its more well known qualities. We start seeing depictions of the more secret or complex tiger, both in art and through documentaries showing that these creatures are indeed three dimensional, and deserve more than we have given them. Through study and slow understanding of how tigers live, we find what is making them disappear and can possibly cut down on the deforestation and poaching for their sake. It will take a unified effort to save these unique beasts.

Tigers and Royal Tigers

There has been much confusion over time between the description of tigers and leopards, like someone relaying a story about a “large white spotted tiger being seen” or the story of some kind of all black tiger, which was most likely a black panther. Throughout many Asian and African languages, the word to describe either of these animals has been “tiger” or “harimau” in Sumatran, hence the confusion. The term used to specifically describe a larger wild cat with an orange coat, white belly, and black lateral stripes crossing over its back and down each side is “royal tiger” or “harimau belang” in Sumatran. This web page is dedicated to Sumatran “Royal Tigers,” but if you would like to learn more about leopards, please visit my peer’s page here: Neofelis nebulosa

Man-Eaters

Wherever tigers roamed, they were traditionally revered. In India on roads prone to tiger attacks, locals took to wearing masks of faces on the backs of their heads to discourage tigers from attacking, the myth being tigers are unable to look a human in the eye. In actuality tigers are used to attacking with the element of surprise, so the majority of tigers who think they’ve been seen will retreat. It is rather unnerving to think there is a predator that could hunt humans, we who have elevated ourselves out of the food chain. According to many, tigers come in three categories: game-killer, cattle-lifter, and the man-eater. Man-eaters are by definition those tigers that are driven to hunt and eat humans and while hundreds of cases of man-eating tigers exist and can not be denied, the reasoning is simpler than you might think. As Sumatra (like other eastern areas) began to develop, its governing body started clearing land for plantations, railways, and military outposts, importing much of the labor for the construction from foreign lands where tigers were not a threat. The larger concentrations of workers without the local “coping mechanisms,” plus deforestation  leaving the habitat unable to sustain the then current tiger population, meant that attacks increased drastically and threatened whole enterprises. The fear and loathing felt by many in regards to tigers is directly inspired by the existence of man-eating tigers (see right, a man-eater said to have eaten some 200 men, women, and children). Large groups of men set about hunting down these tigers whenever they popped up, Jim Corbett being a notable Englishmen, known for “retiring” 33 recorded tigers and leopards in India between 1907 and 1938. There is a national park named in his honor for the conservation and photographic work he did for wild animals post hunting.

leaving the habitat unable to sustain the then current tiger population, meant that attacks increased drastically and threatened whole enterprises. The fear and loathing felt by many in regards to tigers is directly inspired by the existence of man-eating tigers (see right, a man-eater said to have eaten some 200 men, women, and children). Large groups of men set about hunting down these tigers whenever they popped up, Jim Corbett being a notable Englishmen, known for “retiring” 33 recorded tigers and leopards in India between 1907 and 1938. There is a national park named in his honor for the conservation and photographic work he did for wild animals post hunting.

Observations

For the better part of April and May 2012, I spent about 3 hours a week observing the Sumatran Tigers in the Asian Forest exhibit at the Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium, in Tacoma Washington. Point Defiance is blessed to have four Sumatran Tigers rotating through different enclosures at their Zoo, and wanting to focus on a single subject for my work over the quarter, I chose to observe a beautiful young tiger named Malosi, who was recently transported from Hawaii in order to mate with the Zoo’s female tiger named Jaya. Although my trips to the zoo did not always coincide with when Malosi was out for viewing, A majority of my notes did end up being about him, and I like to think I got to know him best over the weeks. Some of my observation notes and sketches have been added below, as well as a flood of images and video that I hope will bring you closer to these tigers (Malosi, Bima, and Jaya).

When I first started coming to the zoo I was rather distraught thinking of these incredible creatures so confined and “displayed,” but after spending hours and hours here observing I am resigned without a better solution. The people who work at Point Defiance are very careful and caring individuals who always put the interests of the animals first. Because of their current conditions, most of these animals would not survive in the wild, so they need to be taken care of. While nothing can compare to the wild forests and plains a tiger holds so dear, by working in zoos they help bring more awareness to the plight of their rapidly disappearing species, and the zoo itself gives vast amounts of money and human effort to the protection of wild animals and their habitats every year. It is for each of us to decide how we feel about zoos, taking into account that not all zoos are created equal, but for lack of a better alternative I think many zoos like Point Defiance are doing a grand job.

Malosi the Sumatran tiger. He is very aware of the other male tiger Bima across the observation stage. (Video Credit – Delaine Woods @ The Point Defiance Zoo)

Malosi enjoying a stump. (Video Credit – Delaine Woods @ The Point Defiance Zoo)

Jaya gnawing on some choice beef. (Video Credit – Delaine Woods @ The Point Defiance Zoo)

Male Sumatran Tiger “Malosi” (Focus).

3 years old, born in Honolulu Hawaii.

Observed at the Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium

Male Sumatran Tiger “Bima”.

2 years old, born in Tacoma, Washington.

Observed at the Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium

Delaine Woods

4/29/2012

Three Part Invention

Perspectives

Life

This is my life. I’m here. I’m waiting.

My world is small and full of eyes watching, waiting and wanting.

Move and observe, move and observe. Make sure everything is how it was moments ago.

What is that? Is that new? No, that’s just a log…

I sit with my back to the eyes.

I have memories, or what I think are memories. My mind is full of these small worlds, these easy hunts, these eyes.

Often I am plagued by my reactions. I hear a cry and a flash of emotion spurs me. I want to protect, to hunt, to search.

But all I ever meet is the eyes.

More than metal, the eyes cage me.

So I wait.

Glass

The Glass

The Glass is clear

The Glass is clear and we see

The Glass is clear and we see a Tiger

The Tiger.

The Definition of a Tiger.

It is orange.

It is striped.

It has a large head, big fangs, and a tail.

The glass keeps us safe.

The glass keeps the Tiger safe.

The eyes go through the glass.

Then there are moments when we forget the glass.

Just for an instant it does not feel like we are watching a tiger, but like the tiger watches us.

There is no way to know his question, and no way to answer.

And then,

We are back at the zoo.

Looking at glass.

Looking at a tiger.

Knowing

As humans, we know what it means to confine and enslave

We know what it means to rebel and be free

There is so much put towards our own freedom and its importance

And still we expect our animal others to live where we could not,

Under control.

I’m standing and watching, listening to the people around me, wondering how things could be done differently.

I know this is how it has been done for centuries, but we should be learning from our past and skip being doomed to repeat it. As we progress through our own inventive nature, we will be responsible for the extinction of so many animals around us. I have no answer for this problem nor do I know if that is a problem, or merely nature. All know is I would rather put effort towards elongating our brother’s survival than ending it. But we all just sit back waiting for things to get better.

We are so wrapped up in thinking about ourselves!

We see the animals in the zoo, and they appear to be surviving just fine. Just like us. We all carry on.

Difference being we are ruining their habitats and destroying their families.

It’s Natural.

I have completely forgotten the tiger right in front of me.

Master Tiger Citations

Cultural and Natural Histories

Alexander, Caroline. “A CRY For The TIGER.” National Geographic 220.6 (2011): 62. MasterFILE Premier. Web. April 30 2012

Boomgaard, Peter. Frontiers of Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600-1950. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2001. Print. Yale Agrarian Studies Ser.

Guggisberg, C A. W. “Wild Cats of the World.” New York: Taplinger Pub. Co, 1975.

Print.Johnsingh, A. J. T., and S. P. Goyal. “Tiger Conservation In India: The Past, Present And The Future.” Indian Forester 131.10 (2005): 1279-1296. Biological Abstracts 1969 – Present. Web. April 30 2012.

Leif, Dahlberg. “Put A Tiger In Your Text: Metalepsis And Media Discourse.” NORDICOM Review 31.1 (2010): 103-114. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. April 30 2012.

Liao, Sabrina. Chinese Astrology: Ancient Secrets for Modern Life. New York: Warner, 2001. Print.

Linkie, M., Wibisono, H.T., Martyr, D.J. & Sunarto, S. 2008. Panthera tigris ssp. sumatrae. In:IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. May 7 2012. <www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/15966/0>

Maddison, D. R., and K. S. Schulz. “Tree of Life Web Project.” Tree of Life Web Project. 2007. Web. 10 Apr. 2012. <http://tolweb.org/>.

Mosher, Dave. Oldest Tiger-like Skull Yet —Hints Evolution Got It Right From Start. October 18 2011. http://news.nationalgeographic.com. April 30 2012. <news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/10/111018-fossil-tiger-skull-panthera-science-oldest-china-evolution/>

Mazák Vartislav. “Mammalian Species Panthera tigris.” The American Society of Mammalogists. (1981): 8. Web. April 30 2012< http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-152-01-0001.pdf>

Mazák, Ji H., Per Christiansen, and Andrew C. Kitchener. “Oldest Known Pantherine Skull And Evolution Of The Tiger.” Plos ONE 6.10 (2011): 1-11. Academic Search Complete. Web. April 10 2012.

Nakhla, Saraya. “Indonesian Culture and Tradition.” Sumatran Tiger (Panthera Tigris Sumatrae) ~. 12 Mar. 2011. Web. May 2 2012. <pholoroid.blogspot.com/2011/03/sumatran-tiger-panthera-tigris-sumatrae.html>.

Nichols, Michael, and Geoffrey C. Ward. “The Year of the Tiger. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 1998. Print.

Nyhus, Philip J., and Ronald Tilson. “Characterizing Human-Tiger Conflict In Sumatra, Indonesia: Implications For Conservation.” Oryx 38.1 (2004): 68-74. Biological Abstracts 1969 – Present. Web. April 30 2012.

Oswell, A H. The Big Cat Trade in Myanmar and Thailand. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, 2010.

Worldwildlife.org. May 7 2012 <www.worldwildlife.org/what/globalmarkets/wildlifetrade/WWFBinaryitem18568.pdf>

Visual Research Gallery

Click Image for Description and Citation

- Malosi and I

- Basic information about Sumatran Tigers from Point Defiance Zoo.

- ^ A tiger like skull unearthed from 2.5 million year old rock, oldest known complete specimen related to modern big cats, closest to tigers.

- Map of Sumatran TIger Range 2008

- The Cover of my Animal Book

eBestiary page: “Sumatran Tiger (Malosi)” by Delaine Woods. June 2012

Program: “Animal Others: In Image and Text.” TESC.