Enhydra Lutris

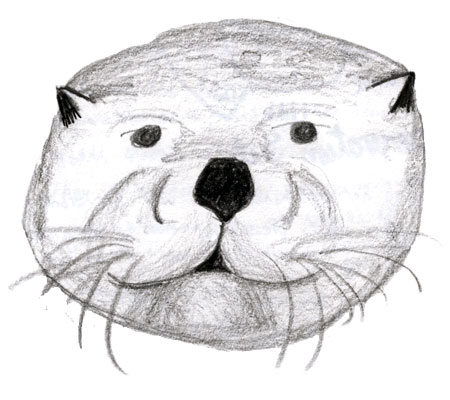

“Also, on a completely subjective note, otters are ridiculously adorable.” – from reflections on 4/13/2012

Introduction

One of my fondest memories from my childhood is going to the Monterey Bay Aquarium with my great-grandmother and watching the sea otters frolicking amongst the kelp in their tank. A lifelong lover of felines, I remember thinking that the otters’ pointed faces and whiskers meant that they were “water cats,” a term that stuck with me long after I learned that otters are in no way related to my household pets. When I left the aquarium that day, I left with a copy of “The Adventures of Phokey the Sea Otter: Based on a True Story” by Marianne Riedman, the companion stuffed animal, and a deep reverence for the small mammals that lived on the waves.

One of the suggestions for picking an animal to study for this class was to pick one that we had a preconceived notion regarding. Sea otters immediately popped into my brain. How better to challenge myself than to challenge my lasting belief that otters are, to put it subjectively, adorable? Imagine my glee at discovering that the Point Defiance Zoo in Tacoma housed five such creatures. A half hour drive, one zoo membership, and a downhill hike later, I was face-to-face with a “Water Cat”.

pick one that we had a preconceived notion regarding. Sea otters immediately popped into my brain. How better to challenge myself than to challenge my lasting belief that otters are, to put it subjectively, adorable? Imagine my glee at discovering that the Point Defiance Zoo in Tacoma housed five such creatures. A half hour drive, one zoo membership, and a downhill hike later, I was face-to-face with a “Water Cat”.

At first, I tried to focus my studies on just one sea otter, a female by the name of Homer. Homer presented an easy subject, as she was much lighter in color than her companions. However, I shortly came to realize that this was due to age (she was 24), a factor which also led her to be significantly less energetic than the others. By my second observation session, I had expanded my note-taking to include all five of the sea otters present; Homer, Libby, Kaladi, Abra, and Nellie. Over the next seven weeks, I came to know each otter as an individual and observed their unique habits and behaviors, such as Libby’s insistence on shoving items into pipes, or Kaladi’s unexplainable attention to the color yellow. Although I haven’t managed to dissuade myself of my preconceived notion regarding otter cuteness, I learned a great deal about their nature, about the way people look at them, and about how I relate to them.

due to age (she was 24), a factor which also led her to be significantly less energetic than the others. By my second observation session, I had expanded my note-taking to include all five of the sea otters present; Homer, Libby, Kaladi, Abra, and Nellie. Over the next seven weeks, I came to know each otter as an individual and observed their unique habits and behaviors, such as Libby’s insistence on shoving items into pipes, or Kaladi’s unexplainable attention to the color yellow. Although I haven’t managed to dissuade myself of my preconceived notion regarding otter cuteness, I learned a great deal about their nature, about the way people look at them, and about how I relate to them.

Ogling Otters ~ Meet the Raft

Homer: Homer is a 24-year-old female Northern sea otter (born April 1988). She was named after Homer, Alaska, where she was rescued from the Exxon oil spill in 1989. She is the last surviving otter from that spill. She sports a pale yellowish head, a light grey belly, and a dark grey back. Due to her age, Homer tends to be less active than the other otters. She spends a lot of time alone, grooming or sleeping.

Abra: Abra is a 17-year-old female Southern sea otter (born January 1995). She was found stranded in California at two days of age. She lived at the New England Aquarium from January 1997 until April 2004, when she was moved to Point Defiance. She is most often found in the company of Nellie. Abra has a white face, fading to brown around the eyes, and a black body.

Nellie: Nellie is a 15-year-old female Southern sea otter (born June 1996). She was found stranded in California at 14 weeks of age. She also lived at the New England Aquarium from Januay 1997 until April 2004, when she  was transported with Abra, whom she is often seen in the company of, to Point Defiance. Her appearance is nearly identical to Abra’s, although her muzzle is slightly darker.

was transported with Abra, whom she is often seen in the company of, to Point Defiance. Her appearance is nearly identical to Abra’s, although her muzzle is slightly darker.

Kaladi: Kaladi is a 2-year-old female Northern sea otter (born May 2010). She was rescued in Kodiak, Alaska, and brought immediately to Point Defiance, where she was hand-raised by the staff. Homer served as a companion and surrogate playmate while Kaladi was being socialized. Although the displayed information near their tank claims she is the darkest of the five otters, she and Libby differ in appearance only in size (Kaladi is significantly larger). This can be confusing, as the two are rarely seen apart.

Libby: Libby is the baby (and brat) of the raft at only one year of age (born April 2011). Libby was the youngest pup to ever be successfully rescued, being found at one day old in Morro Bay, California. She weighed a mere two pounds. She arrived at Point Defiance in November of 2011, where Homer once again helped her adapt to life there. Libby is by far the most mischievous of the otters, often knocking the others about or nipping at them. She is rarely apart from Kaladi. Libby is almost entirely black, with a slightly lighter head than Kaladi. She is also noticeably smaller.

“Libby shoves half of a shell into the drainpipe. This seems to be a favored activity for her.” – Observation from 4/29/2012

Natural History

Aleut Amulet. 1889. Sculpture. Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, St. Petersburg. Web. 16 May 2012.

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Carnivora

Family: Mustelidae

Genus: Enhydra

The sea otter is the largest member of the Mustelidae family, a fact at odds with the knowledge that they are also the smallest marine mammal. They share this family with organisms such as weasels, skunks, badgers, and ferrets, as well as nearly 70 others. Although their family is quite expansive, they are the only member of their genus, Enhydra. Their next closest relative is the Hydrictis maculicollis, the speckle-throated otter. In addition, they also share ancestry with Lutra Lutra (the Eurasian otter), Aonyx Capensis (the African clawless otter), and Aonyx Cinerea (the small-clawed otter).

Physical Appearance

Size: Varies with location. In California, the average adult male weighs about 90 pounds and the female weighs 35-60 pounds. Alaskan otters tend to be slightly larger, with the males weighing up to 100 pounds.

Length: between 4ft and 5ft. The tail accounts for less than one-third of their total length.

Fur: Sea otters have the densest fur of all mammals at 100,000-400,000 hairs/sq cm (versus the 20,000 hairs humans have on their whole heads). There are two layers to their fur: a dense underfur, which traps air against their skin to insulate them against the cold waters; and a set of longer guard hairs which, when clean, are virtually waterproof. This fur is usually a brown or reddish brown. At birth, the guard hairs are tipped with a yellowish tinge. These grow out over the course of several weeks.

Lifespan: Varies. Sea otters can live anywhere from 10 years to 25 years, depending on their nutrition and living conditions.

Ляпунова Р.Г. Aleutian image depicting Sea Otter hunt. 1963. Unknown. Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, St. Petersburg. Web. 16 May 2012.

Physical characteristics: Sea otters have round heads with fairly flat tops, small pointed ears, and oval bodies. Their bodies often appear sac-like due to flaps of skin under the arms that serve as pockets for when the otters are bringing food up from the ocean floor. The sea otter differs from its river-dwelling cousins in many ways, but perhaps most notable is the shape of their hind feet. While river otters possess feet similar to their front feet, well-built for moving about on land, sea otters have flattened, webbed back feet that serve as flippers in the water. These give the sea otters a very odd, uneven gait on land, resulting in a “clumsy” appearance. The forelimbs are shorter and possess retractable claws. In addition, the sea otter also has a flat tail to aid in propulsion.

Vocalization: Sea otters have a variety of vocalizations, but the most  common that I have observed tend to sound like whistles and squeals.

common that I have observed tend to sound like whistles and squeals.

Mating and Social Behaviors: Female sea otters reach sexual maturity around three years of age; males around five years. Sea otters breed any time of year, though there are more common times depending on what location the otters live in. Russian otters often mate between June and July, or September and October. Californian otters mate from July to October. Alaskan otters usually mate in September and October. Gestation takes about six months, and usually results in a single pup. Otters will often form “rafts” of between a few to a few thousand individuals, with male rafts being larger. Female rafts rarely exceed thirty individuals. Males and females generally stay separate except during mating.

Feeding: Sea otters are mainly carnivorous. They eat a list of marine animals nearly 70 species long, including starfish, crabs, clams, mussels, urchins, and sea cucumbers. Otters have a high metabolic rate and may consume up to a third of their body weight per day. Sea otters are unusual in that they often use tools when obtaining food. To break prey out of their shells, the otters will often bring up a rock from the bottom or the shore, rest on their backs with it on their chest, and hit the shells against it until they break open. I have also observed otters hitting the shells on large stationary rocks when smaller ones were not available

Habitat: Historically, sea otters were found all along the Pacific. They ranged from Japan to Russia in the east, and California up to Alaska in the west.

However, overhunting during the 19th century shrank their numbers greatly. They were thought to be extinct in many areas. However, efforts to protect them and being listed as an Endangered Species has helped with their recovery. They stay close to shore, in waters no deeper than 130 feet, although they will travel across deeper water for travel for mating. This is due to the ease of hunting in shallower waters.

“I laugh at the otters’ antics. Kaladi takes notice of my laughter… Libby and Homer also take notice of me. All three of them stare at me… Homer climbs out of the water onto the ledge and watches me. Is she beginning to recognize me?” – Observation from 5/6/2012

Sea Otters in Cultures

In Norse mythology there is a dwarf by the name of Otr (also known as Ottarr, Ottar, Oter,

Kwakiutl Indians. Sea Otter Mask. 1901. Sculpture. University of California, San Diego. Web. 31 May 2012.

Ott, and Otter) who is the son of King Hreidmar. It was said that he had the ability to change forms, and spent many days as an otter, eating fish. He was killed accidentally by Loki. This story begins the Volsung Saga.

Many coastal Native cultures in the Northern Pacific assumed the sea otter to be very close with humans, a kin to them in some ways. The sea otter is found on many totems. The Ainu in the Kuril Islands viewed the sea otter as a messenger between humans and the Creator. Their story the Kutune Shirka is about the wars over a golden sea otter. The Aleuts have a variety of legends that depict despairing lovers or women falling into the sea and becoming otters. Such stories are believed to be caused by the perceived human-like qualities of sea otters. Today, those same qualities have led sea otters to be used as symbols of conservation and environmental responsibility.

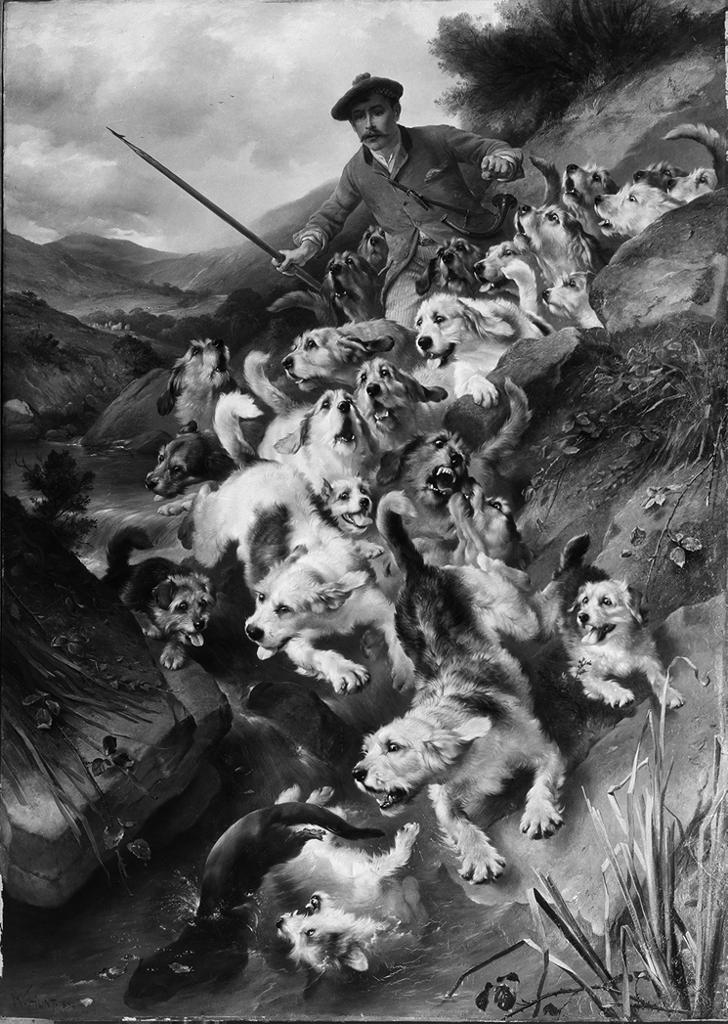

Ekphrasis

Oh, The Devil!

Oh, the Devil’s on my tail

With his spear in hand

And he’s taken the form

Of a great big man

He’ll catch me and kill me

If he can

Oh, the Devil’s on my tail

Oh, the Devil’s on my tail

With his demon hounds

Hear their hard, sharp claws

Digging at the ground

And their growls and barks

Such a frightful sound

Oh, the Devil’s on my tail

Oh, the Devil’s on my tail

My own mama said

That he’ll take me and skin me

And mount my head

She said not to stray

Or I’d end up dead

Oh, the Devil’s on my tail

Oh, the Devil’s on my tail

And the hounds, they bay

As hard as I try

I cannot get away

The sun now sets

On my final day

Oh, the Devil’s got my tail!