For a better understanding of this blog post, please read my previous posts on my trip to Toraja.

Our trip to Sulaewsi was inspired by a guest, Ibu Ana, that visited Green School earlier this year. Ibu Ana came from Toraja to talk to our Eco Art class about the natural pigments that they use in traditional wood carvings. We learned that they use 4 pigments from the region: red, yellow, black and white. No more, no less. So, we thought that by going to Toraja, we would be able to pick these readily-available pigments at the market.

We were so wrong.

On the long drive up to Toraja, we told our guide, Sam, all about the project that we were doing at Green School. Painting with pigments (although none are used in Bali– only natural dyes), getting to the basics of natural materials, working with environmental art. Sam got really excited, because the traditional woodcarvings, and even textiles, are becoming more rare in Toraja. Meaning: fewer artists are being swayed by economics in favor of production. With the rising cost of buffalo mentioned in my previous post, many people, especially women, struggle to make ends meet when they devote their life to their craft.

Toraja Melo is a company that seeks resolve this issue with traditional textiles. Their mission “focuses on solving the feminization of poverty and the rejuvenation of the ‘dying’ hand-weaving heritage in Indonesia” (1). One of the problems with textile production is the high cost of thread imported from Java. Toraja Melo empowers women to preserve the Torajan tenun woven cloth, by making it, teaching it, wearing it, and then ultimately exporting and selling it.

image of ikat weaving

We visited a local village that was abandoned and turned into a workspace for women to weave and sell their textiles. It is still unclear if they use natural dyes in this process. Some weavers claimed that their soft scarves were made from pineapple leaves, but I am somewhat skeptical. Pina fiber is often glossy and stiff, and is an expensive but traditional fiber of the Philippines. After doing some research on Toraja Melo, I discovered that pineapple fibers used to be the main choice for weaving, but are now scarce due to the price (not to mention… the pineapple is considered the ‘king of fruits’ because they take an entire year to harvest!). Most of the textiles here are spun from cotton that is grown at the village, and then dyed from either indigo, red clay, or synthetic dyes.

image of weaving studio in Toraja

Stages of cotton: seed, fiber, fiber spun into thread via loom, then dyed from red clay

One thing I’ve learned while pretending to be a cultural anthropologist is that it’s hard to get to the truth. Even when you’re sitting in the middle of the truth, you have to have a 360 degree angle to begin searching for it. I think that what it really comes down to is time, and having the chance to talk to many different people. Speaking the language and/or having a translator helps immensely, otherwise you are just a spectator. In the search for the 4 pigments of Toraja, I felt like we were on some sort of mystery hunt, piecing together information, running into obstacles, hanging out with dead people (see previous post) and learning bits along the way.

We began our quest at what seemed like the most obvious place– an artisan studio where they make the outer shell of the tongkonan, the traditional boat-shaped houses.

These guys were incredibly skilled craftsman! They explained that they got the black color from mangrove* bark mixed with the sap of the leaf and water, and then using the leaves as their “paintbrush”. This was completely different than what we had heard from another person– that the black was solely from charcoal mixed with tuak, or palm wine. The stages of woodcarving are four parts recessive, starting with the black. The process is like: paint it all black, carve, paint red, carve, paint yellow, carve, then paint white.

*I blogged about mangroves earlier this year– it’s amazing how things come back around!

experimenting with black paint

When we asked these guys about the 3 remaining pigments, they pulled out the red (which is more of an orange), but explained that it came from a place up north– a full days travel– and they couldn’t afford to sell us any, given the hassle of sourcing. They said the yellow came from a similar quarry. And the white comes from a rare, dried white flower crushed into a powder. Where was this white flower? They did not know.

It seems that, given the world wide web, there is very little external information about these 4 pigments in Toraja. Michaela Budiman, a professor of Indonesian Studies at Charles University in Prague, wrote a book about Torajan culture and states that “only four colors are used for tinting the carved ornaments– black, white, yellow and red. Black pigment was traditionally extracted from the soot which formed on the bottom of a pot used for cooking over open fire. Today it is manufactured using gasoline and petroleum. Yellow is made by processing yellow clay and red is made from red soil. The production of white tint was rather complex, as it required a multitude of small snails. Their bodies were extracted from shells which would then be dried and burned until they turned white and subsequently ground into a powder containing lime. At present, a far more simple method of burning limestone is used to produce the pigment. Formerly, the yellow, red, and white pigments were mixed with palm wine (tuak) to make them weatherproof. Today the tuak is generally replaced by varnish, or else purely synthetic pigments are used– those nevertheless not very popular since they fade rather quickly” (Budiman).

Limestone is a far more logical answer for the white pigment. I even found a huge piece on the ground at the textile village.

This information took us to another village, who mysteriously “ran out” of their red and yellow pigments, but confirmed that they used limestone for their white. We then went to the local markets, and (I swear to you) in the darkest corner was a man selling a few small woodcarvings. When we asked him about pigments, he pulled out this bag:

And voila! We were able to purchase 3 kilos off of him. He must have thought we were very strange, but I hope it was worth it to him, because he charged us around $70 USD for the bag. This man confirmed that indeed, the quarry up north was “a day away”, and they would not have been keen to tourists.

1 pigment down, 3 to go!

We then went to Ke’Te Ketsu, a tourist attraction known for it’s woodcarvings. While I was distracted buying some of these beautiful keepsakes, Jen dug a little further in the yellow-pigment-scheme. This time, the guy said he would happily sell us his pigment, but he only had one stone left! Are these people pulling our tails? He did, however, “know a guy” who would be willing to meet us at the coffee shop. This was starting to feel like a funny little drug deal.

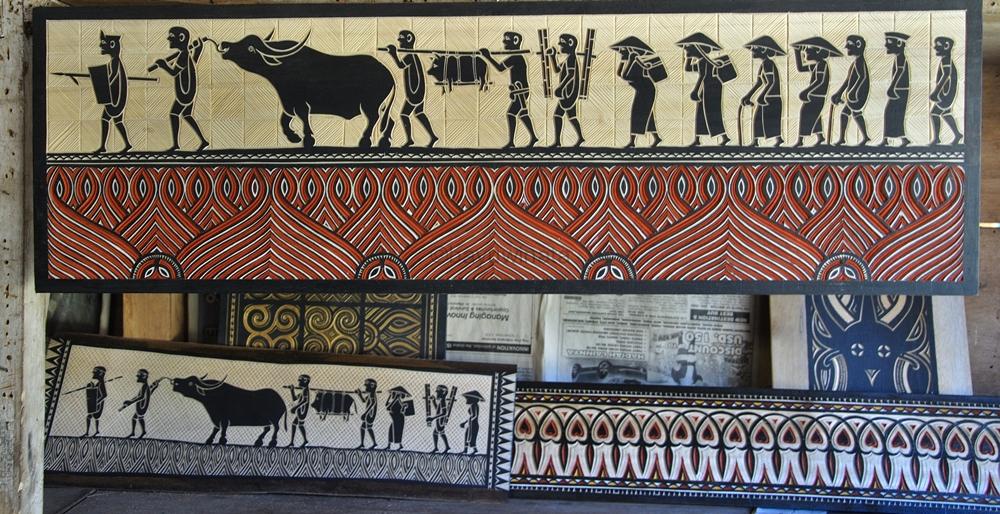

image of wood carvings

Here I got a little more information on the representation of the 4 colors and what they mean to Torajans. The indigenous religion is called Aluk To Dolo or “the Way of the Ancestors”. According to ancient belief, black symbolizes death and darkness; yellow is God’s blessing and power; white is the color of bone, indicating purity; and red, the color of blood, symbolizes human life. These 4 colors are strengthened when used together, and are entirely incomplete when missing one.

Some of the motifs that are used in woodcarvings (both small and on Tongkonan) signify prosperity. The most common symbol is, of course, the buffalo head, which is the epitome of prosperity and a good afterlife. Circular mandala motifs represent the sun, the symbol of power. The golden keris symbolizes wealth. Many of the bottom of the designs are associated with water, which symbolizes life, fertility, and rice fields. Tadpoles represent hope for many children (to pay for that buffalo when you die… badumching!)

Eventually we made our way over to the coffee shop, but instead of finding yellow pigment, we discovered some of the best-tasting arabica coffee, ever. I don’t know how it happened, but later that night on the way to dinner, three young guys who were somehow related to the FIRST guy we talked to approached us with 3 kilos of yellow pigment.

In the end, we returned to Bali with heavy backpacks, happy that we found what we came here for, and having learned more than we could have imagined about a unique culture.

In a recent article published earlier this year, Harvard Art Museum has a pigment library containing 2,500 historical pigments from around the world. I wonder how many of them have come from Indonesia? Sulaewsi?

juxtaposition of new and old– took this photo for SW

References:

Budiman, Michaela, Barbora Štefanová, and Keith Jones. Contemporary Funeral Rituals of Sa’dan Toraja: From Aluk Todolo to “new” Religions. N.p.: n.p., 2014. Print.

Be First to Comment