Order: Accipitriformes

Family: Accipitridae

Genus: Accipiter

Species: Accipiter cooperii

A juvenile Cooper’s Hawk found in Washington, DC, USA, by user Shersydc on Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/sherseydc/2938317609/

Once known as the chicken hawk, the Cooper’s Hawk has been described in the past as a “worse villain” than the “blood-thirsty” Sharp-shinned Hawk (Bent, 1937). The Cooper’s Hawk is a common woodland hawk in North America. It is intermediate in size to the smaller Sharp-shinned Hawk and the larger Northern Goshawk (Curtis, Rosenfield and Bielefeldt 2006). The taxonomic order Accipitriformes has been split from Falconiformes in more recent years, in a decision made by AOU’s Committee on Classification and Nomenclature (Chesser et al. 2010).

Cooper’s Hawk, Accipiter cooperii, left; Sharp-shinned Hawk, Accipiter striatus, right, chromolithograph, by Louis A. Fuertes, United States Department of Agriculture Yearbook. Accessed on Wikimedia Commons.

Cooper’s Hawk are sexually dimorphic in size, with the females being larger by about one third. (Reynolds, 1972). This is the greatest reverse sexual dimorphism of all the world’s hawks (Curtis, Rosenfield & Bielefeldt 2006).

While there is little to no sexual dichromatism between male and female Cooper’s Hawks, the iris color changes with age, especially in males. The iris color changes from yellow to dark red or orange.There is no support for the idea that male iris color signals male fitness or is a trait used in sexual selection. While eye color changes with age, it is not a reliable indicator of age, because of the variation between individuals (Rosenfield et. al 2003).

Juvenal birds have brown plumage on the dorsal side, and the underside is white with brown streaks. In late summer or fall of their second year, birds molt into their adult basic plumage. Adult plumage is blue-grey on the dorsal side, and the underside is white barred with reddish-brown. (Mueller, Berger & Allez 1981). Wings are relatively short and rounded, and the tail is long, making the Cooper’s Hawk well adapted to hunt and maneuver through dense tree cover (Curtis et al., 2006).

The Cooper’s Hawk can look quite similar to the slightly smaller Sharp-shinned Hawk (Accipiter striatus), but can be subtly distinguished by the Cooper’s Hawk larger head and wider white tip at the end of the tail. However, based on size, a male Cooper’s Hawk may be difficult to distinguish from a female Sharp-shinned Hawk (Seattle Audubon Society).

In the fall, western populations head southward from late August to early November. During fall migration, yearlings migrate about one week earlier than adults, and generally females migrated earlier than males. It is speculated that immature Cooper’s Hawks migrate earlier because they must follow migrating avian prey. Generally, Cooper’s Hawks migrate individually, but are sometimes observed moving in groups of 2-5.

Western populations may overwinter in central and southern Mexico.

Spring migration takes place from March through May. During spring migration, adult males migrate earlier than females, because of the pressure to secure a territory at their breeding ground. From a study of radio-tagged birds, it has been found that migrating individuals actually spend most of their daylight hours perched or hunting, and migration is only a small sliver of their day. Flight speeds of migrating Cooper’s Hawks have been recorded at an average of 47 km/h. (Curtis et al., 2006).

Cooper’s Hawks nest in dense, mature hardwood or coniferous forests. In Oregon, Cooper’s Hawk nesting habitat was found to be tree stands 30-70 years old, with a density of 907 trees/ha. Cooper’s Hawk nests have been found from near sea-level to near timberline elevations (Reynolds 1983). In migratory and overwintering habitats, Cooper’s Hawks are found to prefer forested habitats over open fields or human-occupied landscapes (Curtis et al., 2006).

Cooper’s Hawk have colonized urban environments in North America in more recent years, and are even found to breed in urban sites (Stout and Rosenfield 2010). They have also been found to have an affinity for other human-altered landscapes such as conifer plantations. These altered environments tend to support higher numbers of avian prey, and the structural complexity of urban and suburban environments are similar enough to the Cooper’s Hawk’s preferred hunting environment (Curtis et al., 2006). Some researchers have questioned if urban habitats are acting as ecological traps for the Cooper’s Hawk. In a study done in Arizona populations, urban pairs had larger clutch sizes and nested earlier than non-urban pairs, but urban nests were found to have a failure rate of 52.6% while non-urban nests only had a failure rate of 20.5% (Boal & Mannan, 1999). However, in Wisconsin, urban populations seem to be reproductively successful (Rosenfield, Bielefeldt, Affeldt, & Beckmann 1995).

Cooper’s Hawks prey on medium-sized birds such as robins as well as small mammals like squirrels and mice (Seattle Audubon Society). Both feet are usually used to seize the prey, and then the feet grasp, relax, then clench the prey. Cooper’s Hawks have been observed drowning their prey. They are also known to prey on songbird nests. In the breeding season, most prey captured is ground-feeding animals (Curtis et al., 2006).

Vocalization is necessary between pairs because of the density and low visibility of their woodland habitats. Females have a range of more calls than males do, as a way to convey more information because females control male-female interactions (Rosenfield & Bielefeldt, 1991).

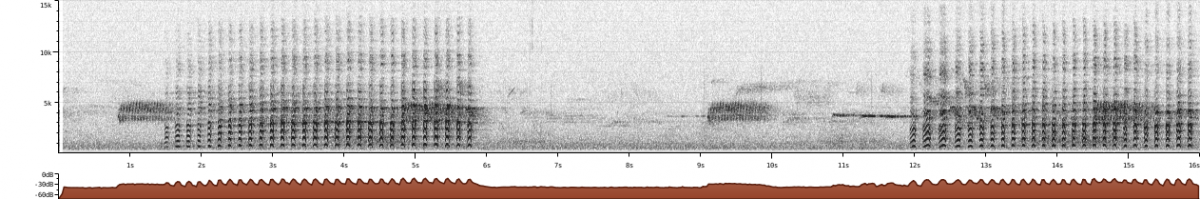

Sonogram of Bruce Lagerquist’s recording of Cooper’s Hawk in King County, WA. Taken from xeno-canto.org.

This call is the “cak-cak-cak” given by both sexes when defended the nest.

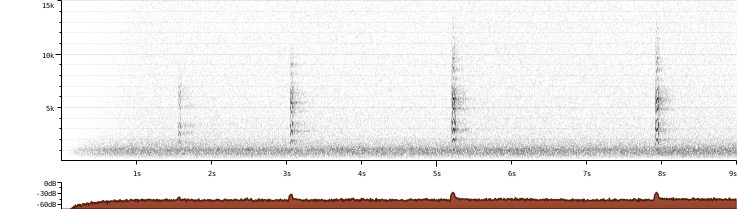

Sonogram of recording of Cooper’s Hawk call by Rachel Hudson at Sunset Beach, Clatsop County, OR. Taken from xeno-canto.org.

Audio Player

This call is the “kik” that mainly males, but sometimes females, will make to tell their mate where they are.

When hunting, Cooper’s Hawk usually flies close to the ground or under tree canopy, but can carry prey anywhere from 30-100m high (Murphy, Gratson & Rosenfield, 1988). During the breeding season, individuals are more likely to be aggressive toward intruders of the same species and sex (Boal, 2001). Outside of the breeding season, Cooper’s Hawks exhibit solitary behavior.

A new behavior has been described in Cooper’s Hawks recently, called proning. Fledglings who are capable of flight have been observed lying with their bodies prone to a tree limb or the ground near the nest tree. On narrower branches they will use wings to secure themselves. Proning has been observed as an individual or group activity, which goes against previous beliefs that young raptors do not stay together outside of the nest to reduce the risk of predation (Rosenfeld & Sobolik 2014).

Cooper’s Hawks are socially monogamous, but extra-pair copulations do occur. Floater males engage in extra-pair copulation with territorial females, and that this may be explained by females maximizing their energy intake to produce eggs, because males present females with food before breeding (Rosenfield, Sonsthagen, Stout & Talbot, 2015).

Cooper’s Hawks are generally in their nesting sites in late March. The average clutch completion date is May 14th. Incubation lasts around 30-32 days. The young fledge around 29 days, and after fledging, the young stay in the vicinity of the nest and get fed by adults for 30-50 days. Average clutch size is 4-5 eggs, and rarely 6 (Reynolds, 1983).

Sex ratios are skewed toward males at conception, the nestling stage, and fledgling stage. One possible explanation is that offspring sex ratios should be skewed toward the “cheaper” sex, which in the case of Cooper’s Hawk is the male, because they are much lower in mass than females at fledgling (Rosenfield, Bielefeldt & Vos, 1996). However, this divergence in size does not apparently lead to siblicide or male starvation (Curtis et al., 2006).

Male Cooper’s Hawks act as the main food provider for himself, the female, and the hatched young. Females rarely hunt during the pair formation until the mid-nestling stage. Males only incubate the eggs when the female leaves the nest to consume the prey the male has brought her. At mid-nestling stage, the female begins leaving the nest to forage for prey as well (Reynolds, 1972).

Historically, the Cooper’s Hawk was heavily persecuted by humans due to its identity as a “chicken hawk”, and it was “cordially hated by poultry farmers” (Bent, 1937). The human impact on Cooper’s Hawk in the early 1900s was more well-documented in the east than the west. Since that time, Cooper’s Hawk populations have recovered well, partially due to its ability to colonize more urban environments. In the late 1940s and 1950s, there were decreases of 7-19% of eggshell thickness due to DDT, but after regulation of DDT, eggshell thickness slowly returned to average.

Because rural Cooper’s Hawks depend on dense forest, logging has a negative impact on habitat. Because of the diversity of nest sites and density that have been studied, it is unclear what the magnitude of habitat degradation is on Cooper’s Hawks (Curtis et al., 2006).

Urban Cooper’s Hawks are susceptible to high mortality rates from window collisions (Hager, 2009).

Bent, A. C. (1937). Life histories of North American birds of prey, Part 1. U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull. 167. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5479/si.03629236.167.i

Boal, C., & Mannan, R. (1999). Comparative Breeding Ecology of Cooper’s Hawks in Urban and Exurban Areas of Southeastern Arizona. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 63(1), 77-84. doi:10.2307/3802488

Boal, C. W. (2001). Agonistic Behavior of Coopers Hawk. Journal of Raptor Research, 35(3), 253-256. Retrieved from https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/jrr/v035n03/p00253-p00256.pdf.

Chesser R. Terry, Richard C. Banks, F. Keith Barker, Carla Cicero, Jon L. Dunn, Andrew W. Kratter, Irby J. Lovette, Pamela C. Rasmussen, J. V. Remsen, James D. Rising, Douglas F. Stotz, Kevin Winker; Fifty-First Supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union Check-List of North American Birds, The Auk: Ornithological Advances, Volume 127, Issue 3, 1 July 2010, Pages 726–744, https://doi.org/10.1525/auk.2010.127.3.726

Cooper’s Hawk. (n.d.). Seattle Audubon Society. Retrieved from http://www.birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/coopers_hawk#

Curtis, O. E., R. N. Rosenfield, and J. Bielefeldt (2006). Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.75

Hager, S. B. (2009). Human-Related Threats to Urban Raptors. Journal of Raptor Research, 43(3), 210-226. doi:10.3356/jrr-08-63.1

Henny, C., Roger A. Olson, & Fleming, T. (1985). Breeding Chronology, Molt, and Measurements of Accipiter Hawks in Northeastern Oregon. Journal of Field Ornithology, 56(2), 97-112. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4512996

Mueller, H., Berger, D., & George Allez. (1981). Age, Sex, and Seasonal Differences in Size of Cooper’s Hawks. Journal of Field Ornithology, 52(2), 112-126. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4512633

MURPHY, ROBERT K. & W. GRATSON, MICHAEL & Rosenfield, Robert. (1988). Activity and habitat use by a breeding male Cooper’s Hawk in a suburban area. Journal of Raptor Research 22. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242538019

Reynolds, R. (1972). Sexual Dimorphism in Accipiter Hawks: A New Hypothesis. The Condor, 74(2), 191-197. doi:10.2307/1366283

Reynolds, R. T. (1983). Management of western coniferous forest habitat for nesting accipiter hawks. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237570329.

Rosenfield, Robert & Bielefeldt, John. (1991). Vocalizations of Cooper’s Hawks during the Pre-Incubation Stage. The Condor. Condor 93:659-665.. 10.2307/1368197.

Rosenfield, R. N., Bielefeldt, J., Affeldt, J. L., & Beckmann, D. J. (1995). Nesting density, nest area reoccupancy, and monitoring implications for Cooper’s Hawks in Wisconsin. Journal of Raptor Research, 29(1), 1-4. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239590288.

Rosenfield, R., Bielefeldt, J., & Susan M. Vos. (1996). Skewed Sex Ratios in Cooper’s Hawk Offspring. The Auk, 113(4), 957-960. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4088881

Rosenfield, R., Bielefeldt, J., Rosenfield, L., Stewart, A., Murphy, R., David A. Grosshuesch, & Bozek, M. (2003). Comparative Relationships among Eye Color, Age, and Sex in Three North American Populations of Cooper’s Hawks. The Wilson Bulletin,115(3), 225-230. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4164563

Rosenfield, R. N., & Sobolik, L. E. (2014). Proning Behavior in Coopers Hawks (Accipiter cooperii). Journal of Raptor Research, 48(3), 294-297. doi:10.3356/jrr-13-86.1

Rosenfield, R., Sonsthagen, S., Stout, W., & Talbot, S. (2015). High frequency of extra-pair paternity in an urban population of Cooper’s Hawks. Journal of Field Ornithology, 86(2), 144-152. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24617893

Stout, W. E., & Rosenfield, R. N. (2010). Colonization, Growth, and Density of a Pioneer Coopers Hawk Population in a Large Metropolitan Environment. Journal of Raptor Research, 44(4), 255-267. doi:10.3356/jrr-09-26.1

Toland, B. (1985). Food Habits and Hunting Success of Cooper’s Hawks in Missouri. Journal of Field Ornithology, 56(4), 419-422. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4513068

Leave a Reply