Introduction

The Hooded Merganser is a small duck identifiable by its crested head, which is a warm brown in adult females and black with a white spot on either side on adult males. This crest can be spread opened or closed, which can cause their crests to be much less prominent. When the crests are folded closed, Hooded Mergansers can be slightly harder to recognize from a distance (“Hooded Merganser” BirdWeb). They are common diving birds which can be seen capturing aquatic insects, small fish, and crustaceans on streams, lakes, and protected oceans (Dugger, Dugger and Fredrickson 2009). It is closely related and in many ways similar to the Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula), but it is smaller and less aggressive (Sénéchal, Gauthier, and Savard 2008).

Hooded Mergansers are a sexually dimorphic species. When in breeding plumage, the male has thinly barred warm brown sides and a black back with a few narrow white stripes on it. The face is black overall, and the hooded appearance is caused by the black rim which encircles the white spots on either side of the crest. It has yellow eyes and a white breast with black stripes down either side of it. The females are a cool brown all over their bodies, lighter on the breast and belly and darker on the back and wings. They have thin white stripes on the ends of their wings. The crest of the female is a cinnamon brown, and their eyes are yellow. They have long, thin, serrated black beaks (“Hooded Merganser” BirdWeb).

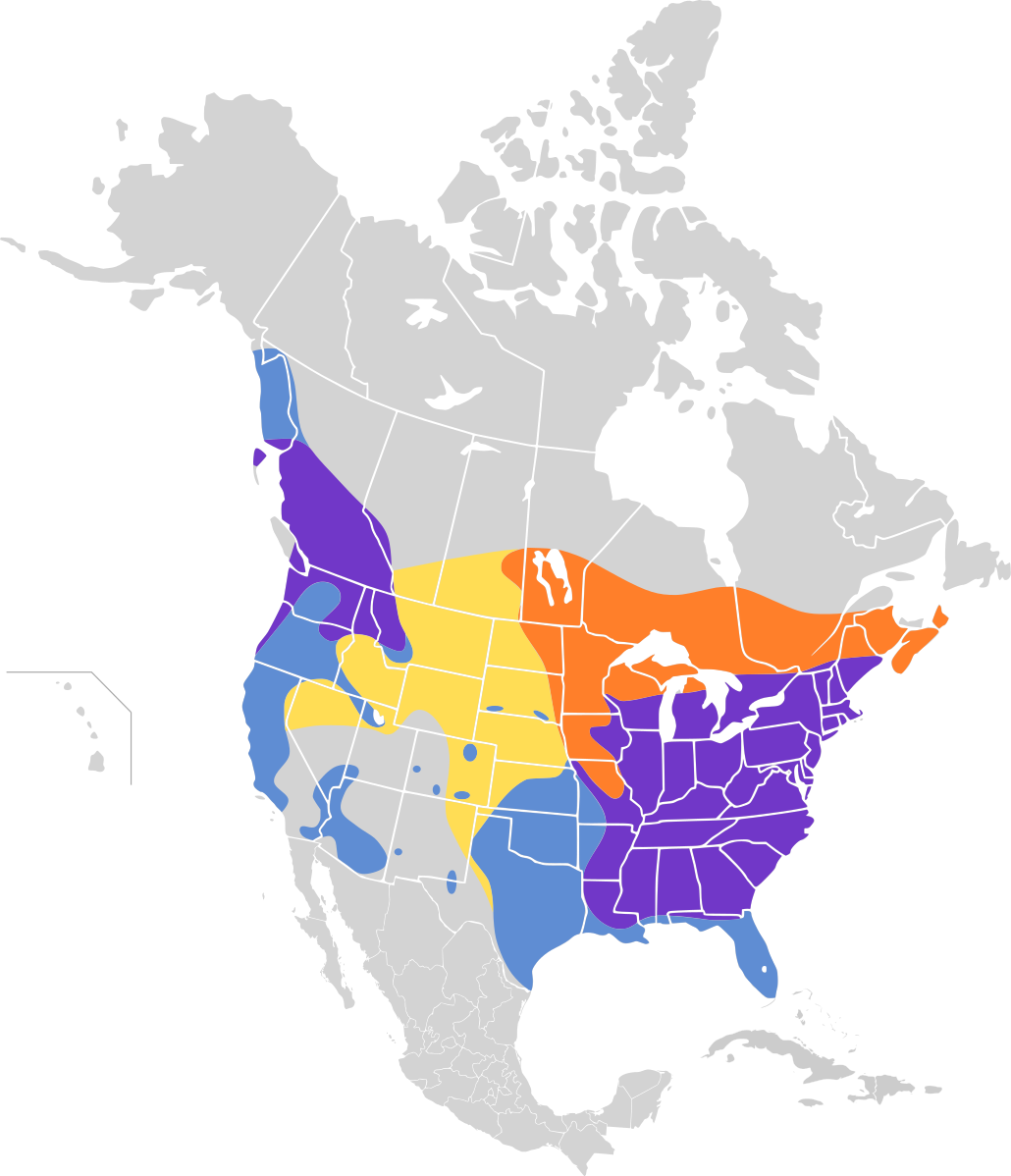

Hooded Mergansers live exclusively in North America, straying as far south at times as Hispaniola, an island in the Caribbean (Sénéchal, Gauthier, and Savard 2008, Pedro and Rodríguez 2018). This is quite rare, though, and they are considered vagrants in those areas (Pedro and Rodríguez 2018). There are also records of them in small numbers on the Baja Peninsula in California, though they are very rare there (Carmona, Ayala-Perézand Aguilar 2011).Hooded Mergansers breed and winter in forested water areas in North America, including around the Evergreen State College. They are very common in the Great Lakes area (Morse, Jakabosky, and McCrow 1969, Dugger, Dugger and Fredrickson 2009). It seems that most Hooded Mergansers are short to intermediate migrants, rarely straying far from the North American continent. Late migrants migrate in fall, early migrants in spring. They migrate alone, in pairs, or in small flocks at night, and tend to do so gradually instead of all at once (Bellrose 1976a, Dugger, Dugger and Fredrickson 2009).

Hooded Mergansers are cavity nesting ducks which live in boreal forested areas near bodies of water or in wetlands (Sénéchal, Gauthier, and Savard 2008). They seem to prefer high canopied forests that are more open in the understory. They do not tend to create nests in areas that are surrounded by large numbers of closely dispersed trees. Hooded Mergansers prefer to live near small lakes at least when they are pairing, possibly because of their preference to dive in waters less than 10 meters deep for their food (Holopainen et. al 2015).

They are very small ducks, so the cavities they nest in do not have to be as big as other cavity nesting ducks. According to one study, the minimum cavity size chosen by Hooded Mergansers was 6 cm × 6 cm, and most of the cavities were caused by either broken limbs causing decay or by Pileated Woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus). Most of the cavities Hooded Mergansers nest in are snags, though some are living trees (Denton et. al 2012, Sénéchal et. al 2008). They also are often willing to nest in man-made boxes; in fact, a recent study shows that Hooded Mergansers may be taking over Nest boxes intended for Wood Ducks, which is an expression of the competitive nature involved in obtaining a good cavity or nesting box (Heusmann and Stolarski 2017).

Unlike Red-Breasted Mergansers and Common Mergansers, Hooded Mergansers are not strictly piscivores. They do eat small fish, but they also eat aquatic insects and crustaceans (Dugger, Dugger and Fredrickson 2009). Hooded Mergansers are diving birds who prefer to dive in waters between 0 and 5 meters deep, and seem to prefer slack tides when foraging (Holm and Burger 2002).

Hooded Mergansers also have both clear nictating membranes (sometimes referred to as an inner eyelid) and the capability to accommodate light changes by using different lenses to change the way light refracts through their eyes (Sivak, Hillebrand and Levak 1985, Sivak and Glover 1986). It is theorized that these two adaptations in tandem make the Hooded Merganser an extremely skilled hunter by sight.

Audio Player

Recording from xeno-canto by Russ Wigh. A male Hooded Merganser doing a rolling frog-like display call during courtship.

Audio Player

A call of a Hooded Merganser from xeno-canto by Paul Marvin.

Audio Player

Female alarm call from xeno-canto by Martin St-Michel.

Hooded Mergansers are thought to tend to live around 11 years according to data from the Bird Banding Laboratory, a program run by the United State Geological Survey (Smith 2013). Female Hooded Mergansers do not breed until age two, which is a relatively late age for a bird of its size (Morse et. al 1969). They are monogamous and their pair bonds last from pair formation, which has been observed to occur between November and January, through breeding, which usually happens in March and April, until all the eggs have been laid, which usually occurs in May (Sénéchal et. al 2008). At this point the male abandons the female, who incubates the eggs until they hatch. Eggs hatch in June, and the typical clutch size ranges from about nine to 13 eggs, and nesting success recorded in multiple studies ranges from 57-87% (Sénéchal et. al 2008). However, a study conducted from 1955 to 2007 averaging brood sizes and comparing them over a longer period of time concluded that average brood size for Hooded Mergansers has decreased by 1.45 eggs since 1955 (Schummer et. al 2011).

Hooded Mergansers engage in inter- and intra- specific brood parasitism as an adaptation to increase the chances of survival of their young, though intraspecific much more commonly. Their cousins, Common Goldeneyes (Bucephala clangula), are much more likely to leave eggs in Hooded Merganser nests than Hooded Mergansers are to leave eggs in Common Goldeneye nests, though it does occur (Sénéchal et. al 2008).

Hooded Mergansers take flight by running across water until they have enough momentum to take off, at which point they beat their wings continuously and quickly. They land by ceasing flapping their wings and coming into a glide, then putting out their feet and using them against the water to bring themselves to a stop. They tend to be awkward on land because they are so aquatic based (McGilvrey 1966, Dugger et. al 2009).

According to one study detailing bird reactions and precautions when an avian predator is present, diving birds, including the Hooded Merganser, moved further away from the shore when they knew a Bald Eagle was present (Middleton et. al 2018).

Hooded Mergansers have elaborate courtship behaviors which are very similar to Buffleheads (Bucephala albeola) and to other Mergansers. Male Hooded Mergansers engage in a lot of intricate head movements a part of their courtship rituals, as well as ritualized drinking. Males also make frog-like rolling noises, and females sometimes produce a gack noise (Johnsgard 1961, Dugger et. al 2009).

Hooded Mergansers are not on the 2016 State of North America’s Birds Watch List (Cornell University 2016), and seem to be less affected by the presence of toxins when compared to similar birds (Dugger et. al 2009). In one study where Methylmercury, the most toxic form of mercury that is in the environment, was injected into the eggs of a variety of birds, Hooded Merganser eggs were of the least affected. However, it must be noted that the effects of methylmercury, when injected into an egg, differ from the effects of methylmercury when deposited maternally into the egg, and this study notes that because Hooded Mergansers eat small fish and crustaceans they are exposed to higher dietary concentrations of biologically active methylmercury (Heinz et. al 2008, Rave et. al 2014).

One study compared eggshell thickness of Hooded Mergansers now to their thickness almost immediately after the end of widespread DDT use, as well as to eggshell thickness before exposure to DDT. Though the data immediately after widespread DDT use showed that Hooded Merganser eggs were thinner than was typical, more recent data collected in 2003-2004 showed that the shell thickness had returned back to its pre-DDT state (Rave et. al 2014). This, along with the relatively minimal response to the injection of methylmercury indicates that Hooded Mergansers have some degree of resilience towards environmental pollutants, especially when in comparison to similar species.

Sénéchal, H., Gauthier, G., L. Savard, J. 1 December 2008. Nesting ecology of Common Goldeneyes and Hooded Mergansers in a boreal river system. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 120(4). https://doi.org/10.1676/07-144.1

Kathryn J. Holm, Alan E. Burger. 1 September 2002. Foraging Behavior and Resource Partitioning by Diving Birds During Winter in Areas of Strong Tidal Currents. Waterbirds, 25(3). https://doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2002)025[0312:FBARPB]2.0.CO;2

Morse, T., Jakabosky, J., & McCrow, V. (1969). Some Aspects of the Breeding Biology of the Hooded Merganser. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 33(3), 596-604. doi:10.2307/3799383

The U.S. Geological Survey Bird Banding Laboratory: an integrated scientific program supporting research and conservation of North American Birds; 2013; OFR; 2013-1238; Smith, Gregory J.

David P. Rave, Michael C. Zicus, John R. Fieberg, Lucas Savoy, & Kevin Regan. (2014). Trends in Eggshell Thickness and Mercury in Common Goldeneye and Hooded Merganser Eggs. Wildlife Society Bulletin (2011-), 38(1), 9-13. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/stable/wildsocibull2011.38.1.9

Cornell University. 2016. State of North America’s Birds. http://www.stateofthebirds.org/2016/resources/species-assessments/

“Hooded Mergansers (Lophodytes cucullatus) Use Nest Boxes Designed for Wood Ducks (Aix sponsa): A Changing Demographic,” 129(3)

H W Heusmann, Jason T. Stolarski

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology (1 September 2017)

Heusmann, H. (1975). Several Aspects of the Nesting Biology of Yearling Wood Ducks. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 39(3), 503-507. doi:10.2307/380039

Morse, Thomas & L. Jakabosky, Joel & P. McCrow, Vernon. (1969). Some Aspects of the Breeding Biology of the Hooded Merganser. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 33. 596. 10.2307/3799383.

“Waterbirds Alter their Distribution and Behavior in the Presence of Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus),” 99(1). Holly A Middleton, Robert W Butler, Peter Davidson. Northwestern Naturalist (1 March 2018)

Dugger, Bruce D., Katie M. Dugger and Leigh H. Fredrickson. 2009. Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Sivak, J. G., T. Hillebrand and C. Lebert. (1985). Magnitude and rate of accommodation in diving and nondiving birds. Vision Res. 25:925-933.

Sivak, J. G. and R. F. Glover. (1986). Anatomy of the avian membrana nicitans. Can. J. Zool. 64:963-972.

Holopainen, S., Arzel, C., Dessborn, L., Elmberg, J., Gunnarsson, G., Nummi, P., . . . Sjöberg, K. (2015). Habitat use in ducks breeding in boreal freshwater wetlands: A review. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 61(3), 339-363. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10344-015-0921-9

Notable bird records from Hispaniola and associated islands, including four new species. Steven C. Latta Pedro, Genaro Rodríguez. Dec 24, 2018

Carmona, Roberto, Ayala-Pérez, Víctor, Gutiérrez Aguilar, Antonio, New and noteworthy waterfowl records at artificial wetlands from Baja California Sur, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad [en linea] 2011, 82 (Junio-Sin mes) : [Fecha de consulta: 12 de marzo de 2019] Disponible en:<http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42521043032> ISSN 1870-3453

Heinz, G., Hoffman, D., Klimstra, J., Stebbins, K., Kondrad, S., & Erwin, C. (2009). Species Differences in the Sensitivity of Avian Embryos to Methylmercury. Archives of Environmental Contamination & Toxicology, 56(1), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-008-9160-3a

Braune, B. M., & Malone, B. J. (2006). Organochlorines and Mercury in Waterfowl Harvested in Canada. Environmental Monitoring & Assessment, 114(1–3), 331–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-006-4778-y

Johnsgard, P. A. (1961b). The sexual behavior and systematic position of the Hooded Merganser. Wilson Bulletin 73:226-236.

Schummer, M. L., Allen, R. B., & Guiming Wang. (2011). Sizes and Long-term Trends of Duck Broods in Maine, 1955-2007. Northeastern Naturalist, 18(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1656/045.018.0107

McGilvrey, F. B. (1966b). Nesting of Hooded Mergansers on the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, Maryland. Auk 83:477-479.

Bellrose, F. C. (1976a). Ducks, geese and swans of North America. 2 ed. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

Denton, J. C., Roy, C. L., Soulliere, G. J., & Potter, B. A. (2012). Change in Density of Duck Nest Cavities at Forests in the North Central United States. Journal of Fish & Wildlife Management, 3(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.3996/112011-JFWM-067

Media:

Male and Female Hooded Mergansers .jpg: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hooded.merganser.arp.600pix.jpg

Map of Hooded merganser Distribution .jpg: Dugger, B. D., K. M. Dugger, and L. H. Fredrickson (2009). Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.2173/bna.98

Russ Wigh, XC212480. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/212480.

Martin St-Michel, XC183317. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/183317.

Paul Marvin, XC346073. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/346073.

Leave a Reply