By J.M.Garg (Own work) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

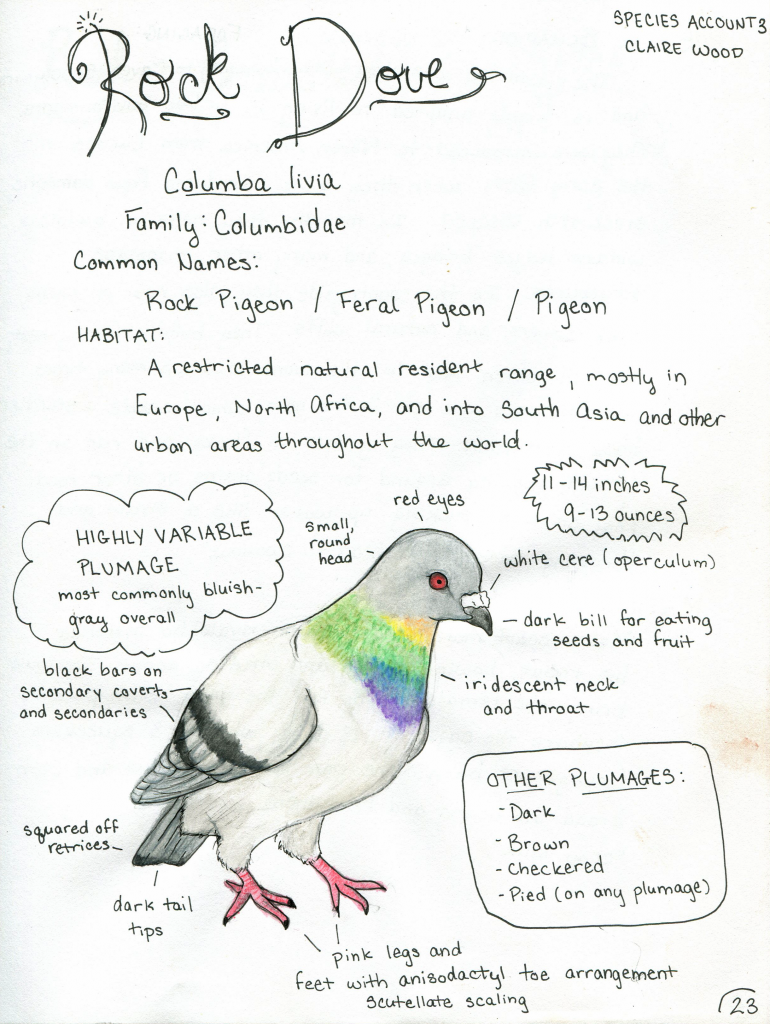

Family: Columbidae

Genus: Columba

Species: Columba livia

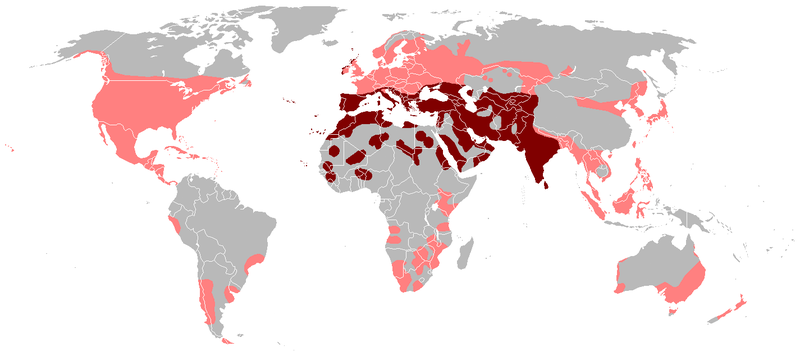

The Rock Pigeon goes by many names, most commonly the Common Pigeon, Rock Dove, Carrier Pigeon, Messenger Pigeon, and the Feral Pigeon as well as the Fancy or Domestic Pigeon. They are also less affectionately known as sky rats, sewer eagles, gutter falcons, and the like due to their omnipresence in so many of our cities worldwide.

It has long served as a symbol, a messenger, companion, food source, and more in human societies. The rock pigeon was introduced to North America in the 17th century when colonists brought domestic pigeons from their settlements in Europe and they escaped from their cages, forming feral populations (Johnston, Bird of North America).

Pigeons have incredible genetic elasticity as pigeon fanciers worldwide, including Charles Darwin, have long known. This allows breeders to manipulate the species into a huge range of different breeds with unique plumage and traits of each one demonstrating the array of possibilities for the species. Darwin used pigeons as a metaphor for mutable changes that can happen within one species, in part because he was able to show how quickly and drastically they were able to change over a relatively short amount of time (Humphries 2008).

A dovecote (or colombier) in Normandie, France Young pigeons (called squabs) were often killed for their tender meat, but the birds were also prized for many other reasons. Dung was collected from the dovecotes and used as a fertilizer and sometimes this was the sole reason for keeping pigeons. Their dung was also used to tan hides and as an ingredient in gunpowder (Humphries 2008). However, it was not as though the birds were being held captive for these purposes, they were free to come and go as they pleased and it is easy to see why they chose to stay. Humans provided pigeons with an ideal nesting environment, a constant supply of easy food, and safety from non-human predators. Columba livia benefited hugely from their relationship with human and so the two species began to co-evolve, and thus spread to all corners of the globe with humans, successfully establishing populations in every continent except for Antarctica. Ectopistes migratorius Chickens soon took the place of the favorite meat bird and escaped domestic rock pigeons were quick to fill the niche that passenger pigeons and exploit a the new niche that no other bird has been able to master and thrive in to such an extent as the pigeon, the urban environment. By Viktor Kravtchenko (Own work) [GFDL or CC-BY-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons By Billy Hicks (Taken using film camera.) [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons Pigeons form build their nest in natural or artificial cracks and crevices and they are generally rather simple. They are built from stiff twigs and any other suitable material that can be found, brought to the site one by one by the male, then arranged my the female into a basic platform with no lining (Sibley 2001). The birds will often reuse the nest year after year and do not remove their feces, which build up and harden, strengthening the nest over time (Humphries 2008). Some feral pigeons have isolated nests and sometime the birds nest in larger colonies, if space allows for it (Johnston 1995). Young Pigeons The ideal clutch size for pigeons is two eggs, but may occasionally vary from anywhere from one to four eggs (Johnson and Johnston 87). They are laid one after another and the first egg laid often has the advantage and will be born larger and is more likely to survive if food is scarce or a parent is lost (Humphries 2008). Female birds incubate the eggs through the night and males take over the job during the day and they will continue this schedule of care after the chicks have hatched. The eggs may incubate anywhere from 14 to 20 days before hatching (Sibley 2001). By Bjørn Christian Tørrissen [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons In urban areas, feral pigeons tend to roost on the roofs of buildings, on ledges, under bridges, on top of posts, poles, and traffic lights, and anywhere else with crevices or with a cave-like structure. They are often roosting in large number and engage in some social beavior with one another. They usually come down to the street and feed during time of high human activity and feed by pecking at seeds and other food material on the ground. They exhibit signs of slight dominance when feeding, but are generally very tolerable of each other (especially when there is ample food) and do not seem phased by human activity, cars, etc (Pers. Ob.). Territoriality Pigeons are not generally aggressive, but both sexes may be aggressive in nest territory (Sibley 2001). Their territorial behavior consists of flying from their nest and display by crouching and shifting position, raising one or both wings, and sometimes pecking or striking the intruder with their wing (Johnston). Other threat displays consist of the bird bowing, inflating its crop, giving a display call, and often raising its wings while it circles the intruder (Goodwin 1983). Threats are most commonly made toward their own species and other species are often ignored. Pigeons like to maintain some distance between individuals, commonly sitting with about two body lengths between bird to prevent a bird from pecking without moving, but it varies with their activity (Gill 2007). During a feeding frenzy, birds may be shoulder-to-shoulder, competing for space (Johnston). Wing flapping can be used to increase feeding space under less crowded conditions (Goodwin 1983). In a study conducted in 1998 by Sol et al. looked at competition for food amongst urban pigeons and noted the aggressive or territorial behavior between individuals. They found that most aggression is directed towards young pigeons and they may be out-competed when there are limited food sources and find alternative resources that are often less desirable (such as food waste). However, as with most species that exhibit aggressive behavior, pigeons have an appeasement behavior of nodding their heads in order to induce a non-aggressive state in their attacker (Wosegien and Lamprecht 1989). Courtship and Mating During courtship, male pigeons will bow and puff out his feathers on his neck and breast while cooing as he struts after the female. Males will also physically hit his wings together, making a clapping sound and alternatively glide with his wings held in a V above the body and his tail fanned out (Sibley 2001). If interested, the female will peck at the male’s beak and preen his feathers and the male will regurgitate some crop milk into her beak in return. Courtship will continue for at least a week before they mate and the nest will then be built by both birds the next day (Humphries 2008). Because it is very important that both parents raise the young, some studies suggest there may be sexual selection taking place with both genders (Johnston and Johnson 1989). The male bird will often drive the female away from other males for mating. (Goodwin 1983). Pigeons “beaking” as a courtship display Locomotion Rock Pigeons walk or run, with head moving back-and-forth, and show good coordination. Their wings are strong (flight muscles make up 31% of body weight) and built for direct flight and they generally fly at less than 70 m altitude, often in flocks. They are generalists in flight, they can hover, glide, fly in extremely windy conditions, and break into flight from standing, but they are especially good at aerial maneuvering (Humphries 2008). Pigeon can also fly a great speeds, in races homing pigeons flights as long as 1100 miles have been recorded. In these competitions their average flying speed over moderate distances (about 500 miles) averages 50 mph), but speeds of up to 110 mph have been observed in top racers for short distance (100 miles) (Walcott 1996). Pigeons clean their feathers daily with powder and preen oil is not used, though bathing in the rain is common. Adult pigeons sleep perched on one leg with other tucked in plumage, head and neck are drawn close to body, and bill tucked into breast feathers (Goodwin 1983). Non-breeding birds may roost in aggregations, or, singly or as a pair, on the nest. Intra- and Interspecies Behavior Pigeons may perform activities such as roosting, sunning, feeding, and commuting either singly or in flocks. However, the birds will flock to avoid predators, one bird will abruptly take off and the others will follow (Humphries 2008). The flock will change direction and individuals will constantly alter their position in the air in order to make themselves harder to capture by a predator (Pomeroy and Heppner 1992). The main predators of pigeons in the city are the peregrine falcon as well as humans, raccoon, opossum, screech-owl, great horned owl, prairie falcon, and crow. Raccoon, opossum, owls, crows, ravens are nest predators as well and will take eggs or squab (Johnston, Bird of North America Online). Homing Pigeons are nonmigratory species and instead show a very strong attachment to their home and are able to find their way home under even the most extreme and novel conditions, a habit known as “homing” which is the subject of much research as well as a huge asset in the relationship to humans. This behavior made domestication of Columba livia easy, once they established their “home” inside of a human habitat, they faithfully returned to that location every night. They were used as one-way messengers, which proved useful for communication home, especially in situations such as war when one-way was all that was needed and other modes of communication often got shut down. Pigeons were used in Europe when cities were under siege in the 1870s where they were used to carry messages back home. A variety of sensory perceptions are used by pigeons when they are attempting to home. Upon release, a pigeon will first use the sun as a compass and studies have shown they follow the change of the sun position with the seasons and when given artificial sunlight for a period of time, they will learn to orient to the incorrect position of the sun (Gill 2007). However, pigeons rely on a multitude of methods to set their direction and will reorient themselves quickly with their internal geomagnetic compass, which also orients them on cloudy days. Magnetite in their skulls, the pineal gland, and photopigments in the eyes of the bird all help it establish it’s internal compass (Johnston 1995). Olfactory and auditory information is also likely to help pigeons orient even in places with strange magnetism Hutchison and Wenzel 1982). Intelligence In one study by Epstein et al. in 1980, two pigeons were placed in separate boxes and had to follow multiple steps and communicate to one another symbolically in order to successfully complete the task. They were able to do so with almost perfect accuracy, an ability that has only been found to exist in chimpanzees and humans. Males also have a louder advertising sound, that sounds like this: Vocal Development Squabs will utter squeaky peeps when demanding food from their parents and then can begin to coo around 30–40 days of age, adult cooing then occurs at 5.5 to 12 months (Johnston 1992). The primary song of rock pigeons is the display coo, which is usually used when courting or, in a different iteration, as a threat and is often a territorial noise. They also have a nest call or advertising coo, an alarm or distress call, and juveniles have a begging squeak (Goodwin 1983). Both genders have the same vocal array and vocalize year round, at any time of day, especially when they are defending their territory and nest. Young pigeons will also snap their beaks and hiss to scare off intruders when they are near the nest. Display flights, which usually include clapping wings together happens post-copulation and in other circumstances involving display flights (Johnston 1992). The wings of pigeons in flight make other distinct and loud sounds as anyone who has startled a flock of pigeons has probably witnessed (Pers. Ob.). Pigeons occupy such a unique niche in which they thrive in human areas that were not made for them, but often work perfectly to suit their needs. They feed off of our waste and handouts and most individuals remain completely separate from the “natural world” throughout their life. Because of this, I find it hard to pose feral pigeons as a negative component to any living systems. They are not displacing other animals and if the pigeons weren’t there we would have significantly less fauna in our cities. However, even as a lifelong vegetarian, I am still in support of pigeon meat making some kind of a comeback in the global market. Humphries, Courtney. Superdove: how the pigeon took Manhattan … and the world. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2008. Johnston, Richard F. and Marian Janiga. Feral Pigeons. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. Sibley, David Allen. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001. Scientific Articles: Goodwin, D. 1983. “Behaviour.” Physiology and behaviour of the pigeon. (Abs, M., Ed.) Academic Press, London. 285-308. Hutchison, L.V. and B.M. Wenzel. 1982. “Activity of central olfactory neurons in the pigeon.” Avian navigation, 362-372. Johnson, Steven G. and Richard F. Johnston. 1989. “A Multifactorial Study of Variation in Interclutch Interval and Annual Reproductive Success in the Feral Pigeon, Columba livia.” Oecologia 80.1, 87-92. Johnston, Richard F. and Steve G. Johnson. 1989. “Nonrandom Mating in Feral Pigeons.” The Condor 91.1, 23-29. Patel, Kruti K., and Courtney Siegel. 2005. “Genetic Monogamy in Captive Pigeons (Columba livia) Assessed by DNA Fingerprinting.” Bios 76.2, 97-101. Rose, Eva, Peter Nagel, and Daniel Haag-Wackernagel. 2006. “Spatio-Temporal Use of the Urban Habitat by Feral Pigeons (Columba livia).” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 60.2, 242-254. Sol, Daniel, David M. Santos, Josep Garcia, and Mariano Cuadrado. 1998. “Competition for Food in Urban Pigeons: The Cost of Being Juvenile.” The Condor 100.2, 298-304. Walcott, Charles. 1996. “Pigeon Homing: Observation, Experiments and Confusions.” The Journal of Experimental Biology 199, 21-27. Wood, Claire. 2012. Field notes taken for an Ornithology class at The Evergreen State College, Ornithology Field Journal, 10/2/2012 – 12/10/2012, The Evergreen State College, downtown Olympia, Interstate 5 ramps, and downtown Los Angeles. Website Resources: BirdLife International (2012) Species fact sheet: Columba livia. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 06/11/2012. Johnston, Richard F. 1992. Rock Pigeon (Columba livia), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://0-bna.birds.cornell.edu.cals.evergreen.edu/bna/species/013doi:10.2173/bna.13 Ehrlich, Paul R., David S. Dobkin, Darryl Wheye. 1988. “The Passenger Pigeon.” Stanford University: http://www.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/Passenger_Pigeon.html. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/106002444/0 http://eol.org/pages/1050069/overview http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Columba_livia/ http://www.pleasebekind.com/pigeon.html http://www.avianweb.com/rockpigeons.html http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Rock_Pigeon/id [/collapsible_item]

By Urban (Own work) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

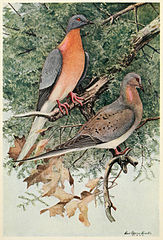

Louis Agassiz Fuertes [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By J.M.Garg (Own work) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Pigeons are diurnal and do not fly at night, they have very bad night vision. They forage early in the day, return to their roosts at mid-day, and then foraging again before nightfall (Humphries 2008). However, this schedule may be adjusting to better fit human schedules and may forage more at mid-day when more food is available (Johnston 1992).

Pigeons are diurnal and do not fly at night, they have very bad night vision. They forage early in the day, return to their roosts at mid-day, and then foraging again before nightfall (Humphries 2008). However, this schedule may be adjusting to better fit human schedules and may forage more at mid-day when more food is available (Johnston 1992).

Pigeons have been the subject of many experiments and thus scientists have learned a lot about their behavior and intelligence. In many of the studies birds are kept just a bit underfed and in turn, birds will work tirelessly for the reward of food, making them easy train (Humphries 2008). Pigeons are particularly good at responding to patterns and images and have a good memory. One pigeon, Linus, learned and was able to recall over 1000 different images and maintained the memory over many years (Humphries 2008). They can separate human-made from natural objects, discriminate different styles of painting, communicate by using visual symbols, and even “lie” (Gill 2007). They are also found to engage in so-called “superstitious” behavior and will continue to perform whatever behavior they were engaged in when they are rewarded, believing the the behavior led to the reward, whatever it may be (Humphries 2008).

Pigeon Cooing

Feral PigeonVocal Array

Nonvocal Sounds

Gill, Frank B. Ornithology. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, 2007.

Epstein, Robert, Robert P. Lanza, and B.F. Skinner. 1980. “Communication Between Two Pigeons (Columba livia domestica).” Science 207, 543-545.

Leave a Reply