Order: Accipitriformes

Family: Accipitridae

Genus: Haliaeetus

Species: H. leucocephalus

Introduction

The Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucophalus) is a striking aerial predator of the North American continent. Now the U.S. National Bird, it graced the skies above it’s homeland well before any European settlers colonized the shores and riverbanks where it resides. The Bald Eagle holds importance among Native American people, as it has for countless generations. A truly inspiring symbol, even in the modern era of technology and development, the Bald Eagle can still capture the imagination of even the most ardent city dweller.

The Bald Eagle is one of only two eagle species in North America, the other being the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). However only the Bald Eagle is endemic to the North American continent, as the Golden Eagle can be found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, and the two species are not closely related. The closest relative of the Bald Eagle is the White-tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) of Eurasia (Love, 1983, p. 11).

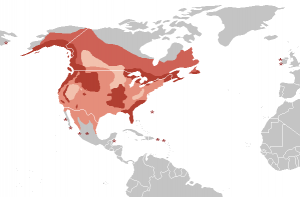

Range of Bald Eagle. Darker coloration shows breeding range, lighter colors are winter and migration areas.

Though the range of the Bald Eagle is very broad, it is typically found near water. Coasts, rivers and inland lakes are the most likely places to see a Bald Eagle (Sibley, 2016, p. 111) This specialization decreases their competition with Golden Eagles, who frequent more inland areas. As the distribution map above shows, the breeding areas for the Bald Eagle tend to follow the coastlines, as well as the major river systems of North America, such as the Columbia and the Mississippi.

Eagles are very opportunistic hunters and feed on a wide array of other animals. They are known to prey extensively on shorebirds such as gulls, cormorants and herons, (Windels, 2016, p. 230) as well as waterfowl, particularly diving ducks (Middleton, 2018, p.22). Bald Eagles often kleptoparasitize other predators such as osprey, stealing their catches (Baron, 1997, p. 129). Carrion is another common source of food for Bald Eagles, anything from salmon (Harvey, 2011, p. 509) to coyotes to small rodents (Stauber, 2010, p. 284). Bald Eagles have also been known to predate on black and white-tailed deer fawns, though they don’t appear to be a frequently sought prey item (Gilbert, 2016, p. 68).

Salmon are also an important food source, especially in the Pacific Northwest when the salmon migrate upstream in the fall. It has been shown that the numbers of Bald Eagle in a given area during the fall and early winter are tied to the amount of salmon in that area during a given season run (Elliott, 2011, p. 1696).

The predisposition to scavenging that Bald Eagles demonstrate may explain why some have been observed raiding landfills.Typically this behavior is exhibited exclusively by immature individuals, presumably because they have not yet developed the skill levels necessary to successfully hunt to the degree that they need to in order to survive (Turrin, 2015, p. 248).

In some areas, Bald Eagles have been observed feeding on the eggs of Herring Gulls and Double-crested Cormorants. This does not seem to be a common food source for Bald Eagles in general, but it certainly occurs in specific areas, perhaps due to shortages of other sources of food (Windels, 2016, p. 231).

Adult bald eagle vocalizing and a juvenile calling (the repetitive cry)

(Recording by James Link for Evergreen’s SURF project summer 2020

Bald Eagles mate for life and will return to the same nest site for many successive years (Wilson, 2018, p. 7347). A pair will add new material to the nest each year, and as a result Bald Eagle nests can grow to be quite large at times, such as the one shown in the photo on the left. In many areas, the nest is primarily composed of large tree branches, however in habitats where trees are scarce Bald Eagles will take advantage of other, less conventional sources of building material. In the Aleutian Islands, off the southwest coast of Alaska, many Bald Eagle nests have been found containing a woody kelp of the genus Pterygophora. The eagles salvage the kelp stalks from beaches when it washes ashore. This resource has become more available in recent years due to increased numbers of Sea Otters in the area, who feed on the Pterygophora’s primary predator, Sea Urchins. Less urchins means more kelp, which means more kelp getting washed up on the beaches, which means more kelp available for eagles to use in their nests (Rechsteiner, 2018, p. 2-3).

Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bald_and_Golden_Eagle_Protection_Act#Bald_eagle

Baron, N. & Acorn, J. (1997). Birds of the Pacific Northwest coast. Renton: Lone Pine Publishing.

Gilbert, S.L. (2016). Bald eagle predation on sitka black-tailed deer fawns. Northwestern Naturalist, 97(1), 66-69. https://doi.org/10.1898/1051-1733-97.1.66

Elliott, K.H., Elliott, J.E., Wilson, L.K., Jones, I. & Stenerson, K. (2011). Density-dependence in the survival and reproduction of bald eagles: linkages to chum salmon. Journal of Wildlife Management, 75(8), 1688-1699. https://doi.org/10.1001/jwmg.233

Harvey, C.J., Moriarty, P.E. & Salathé, E.P.Jr. (2011). Modeling climate change impacts on overwintering bald eagles. Ecology and Evolution, 2(3), 501-514. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.204

Harvey, C.J., Good., T.P. & Pearson, S.F. (2012). Top-down influences of resident and overwintering bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) in a model marine system. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 90, 903-914. https://doi.org/10.1139/Z2012-059

Hodges, J.I. (2011). Bald Eagle population surveys of the north Pacific Ocean, 1967-2010. Northwestern Naturalist, 92(1), 7-12. https://doi.org/10.1898/10-03.1

Love, J.A. (1983). The return of the sea eagle. Cambridge: Cambrigde University Press.

Middleton, H.A., Butler, R.W. & Davidson, P. (2018). Waterbirds alter their distribution and behavior in the presence of bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). Northwestern Naturalist, 99(1), 21-30. https://doi.org/10.1898/NWN16-21.1

Pack, A.N. (1936). Eagle shooting in Alaska. NATURE, 104.

Rechsteiner, E.U. Wickham, S.B. &Wayson, J.C. (2018). Predator effects link ecological communities: kelp created by sea otters provides and unexpected subsidy for bald eagles. Ecosphere, 9(5), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2271

Sibley, D.A. (2016). Sibley birds west: Field guide to birds of western North America. New York: Penguin Random House.

Stauber, E., Finch, N., Talcott, P.A. & Gay, J.M. (2010). Lead poisoning of bald (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and golden (Aquila chrysaetos) eagles in the US inland pacific northwest region—an 18-year retrospective study: 1991-2008. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery, 24(4), 279-287. https://doi.org/10.1647/2009-006.1

Turrin, C., Watts, B.D. & Mojica, E.K. (2015). Landfill use by bald eagles in the Chesapeake Bay region. Journal of raptor Research, 49(3), 239-249. https://doi.org/10.3356/JRR-14-50.1

Wilson, T.L., Schimdt, J.H., Mangipane, B.A., Kolstrom, R. & Bartz, K.K. (2018). Nest use dynamics of and undisturbed population of bald eagles. Ecology and Evolution, 8, 7346-7354. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4259

Windels, S.K., Pittman, H.T., Grubb, T.G., Grim, L.H. & Bowerman, W.W. (2016). Bald eagle predation on double-crested cormorant and herring gull eggs. Journal of raptor Research, 50(2), 230-231. https://doi.org/10.3356/0892-1016-50.2.230

Wright, K.R. (2016). Count trends for migratory bald eagles reveal differences between two populations at a spring site along the Lake Ontario shoreline. PeerJ, 4, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1986

The Bald Eagle is one of the most well known conservation success stories in North America. From the arrival of European settlers in North America, through to the mid-20th century, Bald Eagle numbers plummeted. Over 100,000 Bald Eagle bounties were collected in Alaska between 1917 and 1953 (Hodges, 2011, p. 7), and the mid 1930s saw the Bald Eagle bounty in Alaska at one dollar per bird (Pack, 1936, p. 104). In 1940, the U.S. Congress passed the Bald Eagle protection Act, making the selling, killing or possession of any part of the Bald Eagle a criminal offense. In 1962, this act was amended to include both Bald and Golden Eagles as well as their nests; in addition, exception to this law was given to Native Americans at this time (Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, (n.d.).). Despite the original 1940 legislation, the Bald Eagle still had a bounty on it in Alaska well into the 1950s (American Wildlife Illustrated, 1955, p. 477), and the birds did not gain state-level protection until 1959 (Hodges, 2011, p. 7). In 1972, DDT, which had led to astounding Bald Eagle mortality, was finally banned (Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, (n.d.).), and Bald Eagle numbers gradually began to recover (Elliott, 2011, p.1688)(Wilson, 2018, p. 7347).

In many areas, notably the Pacific Northwest, Bald Eagle populations have rebounded quite successfully (Harvey, 2011, p. 501). Some populations seem to be recovering faster than others however (Wright, 2016, p. 9), and continued conservation efforts are still essential to ensure future population stability of the Bald Eagle throughout its range. Some have postulated that increasing numbers of Bald Eagles in the Pacific Northwest could threaten already depleted populations of prey animals, since as top predators they do have measurable effects on many aspects of the ecosystems they inhabit (Harvey, 2012, p. 910). There is compelling evidence to show that when left undisturbed, Bald Eagle populations will stabilize at sustainable levels which do not strain available resources (Wilson, 2018, p. 7350). However, with climate change now an ever-increasing phenomenon, Bald Eagles may be forced to exploit new avenues of survival if resources such as salmon become harder to come by. If this were to occur, as some models suggest (Harvey, 2011, p. 512), then there is a distinct possibility that such changes could threaten other prey species.

Pacific Northwest ecosystems, and the eagles who depend on them, are facing an unknown future where the complex effects of climate change and other human-caused disruptions will no doubt be upsetting established and reestablished populations of Bald Eagles in the years to come.

Rhiannon Ayley has been a student at the Evergreen State College for 3 years, and a Pacific Northwest resident for 20 years. She has observed Bald Eagles many times during her life, and has had a few very close encounters with them over the years. She hopes this post will inform others about Bald Eagles, and encourages people to recognize how lucky we are to share our home with this magnificent bird.

Page edited 8/22/2020 James Link. Sound file added.

Leave a Reply