Close up Barred Owl taken by Gregory “Slobirdr” Smith Via Flickr

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

Genus: Strix

Species: Strix varia

Introduction

Barred Owls are medium to large sized birds, they can range anywhere from 16 to 37 oz and be as long as 20 inches (All About Birds, 2017). Barred Owls are medium sized owls meaning that they are smaller than owls such as Great Horned Owls but smaller than owls like the Barn Owl or Screech Owls (All About Birds, 2017).

Barred Owls are easily Identified by their prominent vertical striping on their chests and belly along with light striping through the rest of their bodies (James and Mazur, 2000). The juveniles look very similar although the striping is less noticeable(James and Mazur, 2000).

Barred Owls are commonly confused with a native owl, the Spotted Owl, because their plumage looks remarkably similar (National Audubon Society, 2016). The most obvious difference between the two species is that, as the name suggests, Spotted Owls are spotted whereas Barred Owls are streaked (James and Mazur, 2000).

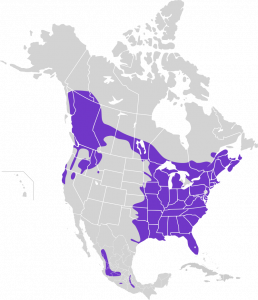

Barred Owls were originally discovered in 1873 in Montana. It wasn’t until the 1960’s that they were even found in the pacific northwest and the mid to late 1970’s that Barred Owls had a foothold all the way through the pacific northwest and the west coast. Part of the reason that the Barred Owls had such a hard and long time expanding their distribution was due to lack of forests within the Great Plains. An increase in forests near the Missouri River was a real turning point in their distribution. The added forests caused them to be able to move further east with more foraging and shelter locations (Livezey KB., 2009).

Barred Owls were originally broken into a northern, and an eastern group. Once there was more tree density within the great plains, the groups combined again and kept moving west toward the pacific. It has been thought that the extra forest growth decades ago was due to European settlers suppressing wildfires causing the forest to grow much denser and further than before allowing the Barred Owls ample habitat to keep moving through (Livezey KB., 2009).

Barred Owls survive in mostly wooded locations. They are seen mostly roosting in locations with easy access to water for hunting (All About Birds, 2017). They nest in both coniferous and deciduous/coniferous forests, with Barred Owls also preferring older and matured growth to newer growth (National Audubon Society, 2016. Singleton, 2017).

Commonly, Barred Owls can be found near or within trees with much thicker basal diameters, although this proves to be less important than how good of a roost sight they have actually found within their tree (Irwin et al, 2017. Singleton, 2017).

Barred Owls will nest and stay in locations with gently sloped grounds as well as they seem to prefer 3/4 tree canopy coverage above them (James, 1998). When Barred Owls are preparing to breed, there is an even higher percentage that will nest solely in old growth with most Owls straying away from any form of younger wood (James, 1998. Gaines et al, 2010). Barred Owls will generally stay within the same 400ha (4 km2) for most of their adult lives, spreading up to 600 ha (6 km2) during non-breeding seasons and staying within a 100 ha (1km2) area during the breeding season (James, 1998). Barred Owls are much more likely to stray further from home in the winter months due to food scarcity and needing to search further for food (Forsman et al, 2007).

Barred Owls are birds of prey. They sustain themselves off of other smaller creatures. According to the analysis of Barred Owl pellets, Barred Owls prefer to hunt and catch prey near water sources (Livezey, 2007). Although they are solely meat eaters, they are opportunistic hunters and will eat multiple varieties of animals dependent on what is most available in the area. Their choices of food vary depending on the season they’re hunting in, although the basic types of creatures they eat remain the same(Livezey, 2007).

If they are hunting in colder months, they will tend to catch more mammals as prey and less birds, amphibians, and reptiles. Barred Owls seem to eat 98% mammals such as rats, mice, small rabbits and hares, and squirrels during the winter months. If needed, they will supplement their diets with birds spiders and fish, as they become available (Livezey, 2007).

Whereas in the warmer months their diets grow to include other variants of creatures as they become more readily available. In the summer months they will eat about 62% mammals, 13.5% birds, 10% insects and spiders, 5% amphibians, 5% earthworms, and a small amount of fish, reptiles, snails, and crayfish. In summer especially, they take advantage of the waters nearby to find their prey. Owls as a species hunt and are most active at dawn or dusk rather than during the heat of the day (Livezey, 2007)

Barred Owls who are found to be living in urban environments have a slightly different diet. Their diets consist of one or two large species of creatures predominantly, such as almost fully rodents and small birds with very little evidence of anything else (Elliott, 2015).

Barred Owls have been known to make many distinctive sounds, the most noticeable being their “Who cooks for you” hoot heard below. A hoot aptly named due to it’s likeness to a person saying that phrase (Mennill and Odom, 2010. Fraser, 1985).

They also are heard with a variety of other hoots such as (Although most people break these hoots into only three groups now instead of all named below (James and Mazur, 2000):

Inspection Call: Single sustained note

Fast ascent: Notes rapidly ascent to a final high pitched note.

Gurgle: Very throaty noise.

Two Note: Heavily accented two note phrase.

Twitter: Variable-pitched squeaky notes.

Scream: Usually an alarm call, one or two notes that ascend and end abruptly.

Three Note: Three evenly space notes of same pitch.

Mumble: Three low notes in a short call.

Two-Phrased Hoot: Two sets of four syncopated notes.

One-Phrased Hoot: Four evenly spaced notes. Often given by females as a call or after an alarm call.

Female Begging: One high pitched sustained whistle.

Ascending Hoot: Many evenly spaced ascending notes.

Short Ascending Hoot: Similar to ascending hoot but has only around 5 notes.

None of these noises have names that they are specifically known as, so these names were taken from Mennill and Odoms 2010 article on Barred Owl vocalizations.

Audio of a Barred Owl with a very prominent “Who cooks for you” hoot. By Wikimedia Commons user Fae.

Audio of noticeable Barred Owl hoots. By Wikimedia Commons user Fae.

Juvenile begging call (a sound made for some time after leaving the nest, like this bird):

James Link, XC582630. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/582630.

(Recording by James Link for Evergreen’s SURF project summer 2020. Image cropped from Xeno-canto Sonogram provided on above webpage)

Barred Owls are born with lots of downy feathers on their body to keep them warm, but they rely on their parents to care for them once they hatch. From a very young age, Barred Owls can be very mobile. Although they won’t be able to fly, they will still explore by grasping things with their talons (James and Mazur, 2000).

Barred Owls tend to not sleep for very long during each rest with the average being about 28% of every hour spent sleeping. They will roost high in trees, sometimes younger owls will nestle within grass below, especially if it’s hot (All About Birds, 2017).

With an increasing amount of urbanization in the Pacific, it’s no wonder that birds, especially owls, are having to breed and spend more of their time within neighborhoods and cities. Even still, there is a remarkable small number of owl-vehicle impacts with Barred owls having no recorded impacts. This is though to be due to the fact that Barred Owls are mostly active during dawn and dusk, as well as them tending to soar/float wherever they are going, most likely high enough to avoid cars (Bates et al, 2015).

Although Barred Owls are most active at dawn and dusk, they are still one of the most active owl species during the day with many reports of spotting them as well as hearing their distinctive calls when walking through parks and forests (All About Birds, 2017. Fraser and McGarigal, 1985).

Although there is little information recorded, Barred Owls are thought to be monogamous with pairs breeding for life, although there are a few instances of single non-breeding owls staying in one area their whole life (James and Mazur, 2017).

All About Birds. (2017). Barred Owl Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved March 3, 2019, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Barred_Owl/id

Bates, J. L., Bierregaard, R. O., & Gagné, S. A. (2015). The effects of road and landscape characteristics on the likelihood of a Barred Owl (Strix varia)-vehicle collision. Urban Ecosystems,18(3), 1007-1020. doi:10.1007/s11252-015-0465-5

Bodine, E. N., & Capalid, A. (n.d.). Can Culling Barred Owls Save a Declining Northern Spotted Owl Population? Retrieved March 3, 2019, from https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=beer

Cody, M., Courtney, S., Franklin, A. B. & Gutiérrez, R. J., (2006). The Invasion of Barred Owls and its Potential Effect on the Spotted Owl: A Conservation Conundrum. Biological Invasions, 9(2), 181-196. doi:10.1007/s10530-006-9025-5

Elliott, J. E., & Hindmarch, S. (2015). When Owls go to Town: The Diet of Urban Barred Owls. Journal of Raptor Research, 49(1), 66-74. doi:10.3356/jrr-14-00012.1

Forsman, Eric D., et al. (1970). Diets and Foraging Behavior of Northern Spotted Owls in Oregon. Nez Perce National Historic Trail – History & Culture, USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Region, Forest Health Protection, Boise Field Office, www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/25515.

Forsman, E. D., Glenn, E. M., & Hamer, T. E. (2007). Home Range Attributes And Habitat Selection Of Barred Owls And Spotted Owls In An Area Of Sympatry. The Condor, 109(4), 750. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2007)109[750:hraahs]2.0.co;2

Fraser, J., & McGarigal, K. (1985). Barred Owl Responses to Recorded Vocalizations. The Condor, 87(4), 552-553. doi:10.2307/1367961

Gaines, W. L., Graham, S. A., Lehmkuhl, J. F., & Singleton, P. H. (2010). Barred Owl Space Use and Habitat Selection in the Eastern Cascades, Washington. Journal of Wildlife Management, 74(2), 285-294. doi:10.2193/2008-548

Irwin, L. L., Rock, D. F., & Rock, S. C. (2017). Barred owl habitat selection in west coast forests. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 82(1), 202-216. doi:10.1002/jwmg.21339

James, P. C. (1998). Barred Owl Home Range and Habitat Selection in the Boreal Forest of Central Saskatchewan. The Auk, 115(3), 746-754. doi:10.2307/4089422

James P. C. and Mazur K. M. (2000). Barred Owl (Strix varia), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.508

Livezey, Kent B. (2007). BARRED OWL HABITAT AND PREY: A REVIEW AND SYNTHESIS OF THE LITERATURE. bioone.org/journals/Journal-of-Raptor-Research/volume-41/issue-3/0892-1016(2007)41[177:BOHAPA]2.0.CO;2/BARRED-OWL-HABITAT-AND-PREY–A-REVIEW-AND-SYNTHESIS/10.3356/0892-1016(2007)41[177:BOHAPA]2.0.CO;2.full.

Livezey KB. (2009). Range expansion of barred owls, part I: chronology and distribution. Am Midl Nat . 161(1):49–56. Retrieved from https://bioone.org/

Livezey KB. (2009). Range Expansion of Barred Owls, Part II: Facilitating Ecological Changes. Am Midl Nat . 161(2):323–349. Retrieved from https://bioone.org/

Mennill, Daniel J., & Odom, Karan J. (2010). A Quantitative Description of the Vocalizations and Vocal Activity of the Barred Owl, The Condor: Ornithological Applications, 112(3), 549–560, https://doi.org/10.1525/cond.2010.090163

National Audubon Society. (2016, October 31). Barred Owl. Retrieved March 3, 2019, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/barred-owl

Singleton, P. H. (2015). Forest Structure Within Barred Owl (Strix varia) Home Ranges in the Eastern Cascade Range, Washington. Journal of Raptor Research, 49(2), 129-140. doi:10.3356/rapt-49-02-129-140.1

Weekes, A. & Wiens, J. D. (2016). Improving strategies to assess competitive effects of barred owls on northern spotted owls in the Pacific Northwest. Fact Sheet. doi:10.3133/fs20113096

One of the biggest problems that Barred Owls are having right now is with people. Although Barred Owls are native to North America, they have just recently expanded their territory immensely causing problems with native creatures they haven’t encountered before (Weekes and Wiens, 2016). More specifically they are having troubles with the Spotted Owls. Spotted owl and Barred Owls are very similar not only in looks, but also in habitat, food usage, breeding grounds and behavior (Livezey, 2009). Where once before it was only Spotted Owls using these things, now the Barred Owls has come into these areas and also needs food, shelter, water, and breeding locations. The only problem is, Barred Owls are much more aggressive than Spotted Owls causing Spotted Owls to lose population rather quickly (Weekes and Wiens, 2016).

Because Barred Owls are playing a role in the decline of Spotted Owl populations, many people think that they should be culled and their numbers decreased just because they according to them they are not a native North American species, even though they are a native species, just not seen as far west as they have now become (Bodine and Capaldi).

Barred Owls are seen as a “Least Concern” animal on their conservation status and their numbers compared to the Spotted Owl are growing at a very rapid pace (Weekes and Wiens, 2016).

Rhian Greaves is a Biological Science student at the Evergreen State College. She wrote this blog entry in Winter 2019 as part of the Birds Inside and Out class.

Page edited 8/22/2020 James Link. Sound file added.

Leave a Reply