Order: Coraciiformes

Family: Alcedenidae

Genus: Megaceryle

Species: Megaceryle alcyon

Introduction

Figure 1: Belted Kingfisher, by Kevin Cole from Pacific Coast, USA (en:User:Kevinlcole) (Belted Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon)) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Banner image: Female Belted Kingfisher with prey by Teddy Llovet [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Size:

Average adult length from beak tip to the retrices is 28-33cm (Fry 1992). The average wingspan is 50-51cm (Sibley 2001).

Distinguishing Features:

Sibley’s (2001) field guide notes that Belted Kingfishers are easily distinguished by their prominent blue crests, large heads, short legs, and dark blue upper breast band. The abdomen, undertail coverts, primary covert wing patch, and lower breast are usually white, though females have some rufous coloration (see below for more information on sex distinctions). Kingfishers have a syndactyl foot where digits two and three are fused the majority of the digits’ length (Proctor and Lynch 1993). This foot is used to assist with burrow excavation (Hendricks et al. 2013).

Sex Distinction:

Females can be distinguished from males by the presence of an additional rufous band across the lower breast below the blue-gray breast band (Fry 1992, Bent 1954). Females also have rufous colored sides, sometimes hidden underneath folded wings (Fry 1992). Unlike males, the central retrices are spotted (Bent 1954).

Adult Plumage:

Belted Kingfishers have the same plumage patterns during both breeding and non-breeding seasons (Sibley 2001). Adult molts occur after the breeding season and before migration between August and October (Bent 1954).

Juveniles:

Young gain their first plumage between two and three weeks of age (Bent 1954). Juvenile plumage is markedly similar to adults with the white collar, shaggy crest, and dark breast band of adults (Sibley 2001). The crest may be slightly darker in juveniles and the white wing coverts are larger (Bent 1954). However, the upper breast band is typically colored with a rufous tone with female young having a larger amount of rufous coloring and some extension onto the sides and flanks (Bent 1954). Juveniles undergo their first molt into adult plumage between February and April of their first year, before breeding season (Bent 1954).

Similar Species:

None throughout North American range, but migrants to Central and South America may be confused with the larger, more rufous colored Ringed Kingfisher – Megaceryle torquata (Fry 1992).

Figure 2: Distribution of the Belted Kingfisher (Yellow: Breeding/Summer Residency, Green:Year-Round Resdiency, Blue:Non-breeding/Winter Residency. By Nrg800 (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Common

North America:

The Belted Kingfisher resides primarily in North America. Their breeding range (yellow, Figure 2) extends from the Pacific to Atlantic coats, northwards to Alaska and Newfoundland and southwards into the southern United States and northern Mexico (Fry 1992, Sibley 2001). Year round residency is limited by ice coverage of feeding habitats at northern latitudes and is seen in green in Figure 2 (Kelly 1998).

Central and South America:

This species is considered a partial migrant (blue, Figure 2) during the winter months to Central and northern South America (Fry 1992). Please see “Habitat:Migration” for further information on migration.

Incidental Sightings:

Sightings have been reported in the Netherlands, Iceland, Ireland, and England (Fry 1992).

Local Distribution:

Belted Kingfishers have been sited throughout the majority of Washington State and Thurston County year round (ebird 2014).

General:

Belted Kingfishers are found alongside streams, estuaries, lakes, rivers, and ponds from sea level up to 2500m in elevation (Fry 1992). Primary habitat requirements are clear waters and elevated perches to fish from (Bent 1954). Territories during both the non-breeding and breeding season are well defined, typically following the course of a waterway or shoreline (Davis 1982). The single occupant during nonbreeding seasons and the occupant and mate during breeding seasons have sole use of the resources within the territory (Davis 1982). Differing studies conflict on average territory size, pointing to a relation of territory size to limiting factors such as nesting sites, food density, and perching sites (Silver & Griffin 2009, Cornwell 1963, Davis 1982, Mažeika 2006).

Non-breeding Territories:

Non-breeding territories are usually smaller than breeding territories and remain fairly constant throughout the winter season (Davis 1982). Davis’ (1982) study on territory size in Belted Kingfishers found an inverse relationship between territory size and food availability in non-breeding territories. As food abundance increased, territory size decreased. Davis also hypothesized that Belted Kingfishers may use environmental cues such as riffle length in streams to determine the quality of habitat and the size of territory needed to sustain an occupant.

Breeding Territories:

Breeding territories are larger than non-breeding and are occupied by a mated pair (Davis 1982). Davis’ (1982) study on territory size in Belted Kingfishers found that the main limitation on breeding territory size and selection are the available nest sites. For further information on nest site selection please see “Breeding:Nest Site” . Access to food and food density near the nest site are secondary factors in territory selection and size though food abundance has a direct positive relationship to the fitness of fledglings (Davis 1982, Mažeika 2006).

Migration:

Partial migrations of Belted Kingfishers from northern to southern latitudes occur between September-October and March-April (Fry 1992, Kelly 1998). Data collected from Christmas Bird counts and the Bird Banding Laboratory show that there is a negative correlation between latitude and the ratio of females to males with females more plentiful further south during the winter months (Kelly 1998). It is unclear why there is a differential migration between the two sexes.

Foraging:

Belted Kingfishers are known for their fishing abilities and fish mainly in clear water of both salt and fresh water bodies (Bent 1954). Strong preference has been shown for fishing in stream riffles – areas of turbulent flow and depths of 5-15cm – over shallow and deep pools (Davis 1982). Kingfishers have also been observed opportunistically fishing at fish hatcheries (Bent 1954). Kingfishers capture prey by making dives from a perch or hovering position up to 15m above water surface (Fry 1992). Dives made from either a perched or hovering position are usually at an oblique angle and can involve a spiral movement (Fry 1992, Bent 1954). Prey is captured within the top 60cm of the water column and sometimes beaten upon a nearby perch to stun it (Fry 1992). Captured fish are oriented into the mouth headfirst before consumption to avoid cuts from any spines (Bent 1954). There is evidence from environmental toxin studies that suggests that mated pairs may forage in differing niches within the same habitat (Evers et al. 2005). Evers et al. (2005) study found statistically significant differences in mercury levels between mated pairs that was found to be attributed to differing foraging niches, not other factors such as prey size and sexual dimorphism as in other species. Data on this subject remains preliminary and limited. Foraging occurs primarily in the morning hours during the breeding season but can occur all day if weather conditions are unfavorable (Cornwell 1963). During winter months in cooler regions kingfishers are found to forage more frequently and be more successful in the afternoons, possibly in preparation for the longer nights or due to the warming of waterways throughout the day (Kelly 1998).

Diet:

Belted Kingfishers are mainly piscivores, but may eat other invertebrate and vertebrate species (Fry 1992). Fish prey species vary depending on location but can include trout, sculpins, sticklebacks, salmon, suckers, shiners, minnows, stonerollers, and others (Fry 1992). Crayfish are not a preferred prey species, possibly due to a lower caloric value, but are eaten during periods where fish are harder to catch (Kelly 1996, Davis 1982). Other non-preferred prey includes frogs, salamanders, lizards, small chicks, and some insects (Fry 1992). Bent (1954) reports instances of Belted Kingfishers eating bivalves and squid in marine and estuarine regions. Belted Kingfishers prefer fish prey of an average length of 9cm, however the bed of the water body may prohibit selective foraging for the preferred prey (Fry 1992, Kelly 1996). Water body beds made of more complex substrates, such as cobblestone, cause kingfishers to take fish prey in similar proportions to the prey’s abundance (Kelly 1996, Davis 1982). A preliminary study on the predator impact of fish species by Belted Kingfishers has shown that they can impact prey fish populations and prey fish size classes in some streams (Steinmetz 2003).

Excrement:

Kingfishers excrete pellets, usually during the night below their roosts (Fry 1992).

Flight:

Typically low and swooping over water bodies but may rise above tree line for long distances (Bent 1954). Wing beats are deep, made in a fast rowing fashion for usually five to six beats before a longer glide (Sibley 2001, Bent 1954).

Social Behavior:

Known to be solitary except during breeding season (Bent 1954). Mates and young may stay in territory and jointly defend territory throughout the young’s first fall (Davis 1982).

Territoriality:

Kingfishers are extremely territorial during both non-breeding and breeding seasons (Davis 1982). Davis (1982) has hypothesized that this behavior may be adaptive as it secures resources for the occupant and prevents other competitors from using those resources. Both males and females respond aggressively to call playbacks of an intruder in their territory and will vigorously chase others out of their territory (Davis 1986, Bent 1954). Territoriality is even observed during migration stopovers where access to food resources may be limited (Hamas 2005).

Vocalizations have different temporal and amplitude variations on a unique harsh rattling call (Bent 1954). Sounds emitted by Belted Kingfishers are below eight hertz (Davis 1986). Mating calls may have a slight “mewing” tone to them (Bent 1954). Davis’ (1986) study on Belted Kingfisher acoustic recognition provides evidence that mated adults can identify each other on the basis of the temporal patterns of vocalizations. This acoustic identification is important during the incubation period when mates in the nest cannot see approaching birds (Davis 1986).

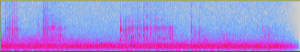

Figure 3: Sonogram of Belted Kingfisher call (Stephanie Lewis, November 10, 2012, near The Evergreen State College on Overhulse Rd. Olympia, WA. 98502)

Belted Kingfisher rattle Sound recorded by Stephanie Lewis, November 10, 2012 Near The Evergreen State College on Overhulse Road, Olympia, WA.

Belted Kingfisher approach call Recorded November 17, 2014, Percival Cove, Olympia WA

Mate Selection:

Belted Kingfishers are typically monogamous and can remain with their mate for multiple years (Fry 1992). White and Cristol’s (2014) study on plumage coloration has suggested that males’ blue coloration might have some bearing on female mate selection. This sexual selection may have brought about an evolutionary lack of rufous coloration in adult males, which is not seen in the closely related Ringed Kingfisher (White and Cristol 2014).

Nest Site:

Belted Kingfishers usually nest on steep banks of fresh and salt waterways but have been found to nest in banks that are not near water (Bent 1954, Cornwell 1963). In areas where winters do not allow for year-round residency, males arrive approximately a month earlier than females to select a nest site (Davis 1982). The selection of a nest site is primarily determined by the slope of the bank, bank height, composition of soil, the availability of food nearby, and uniformity of the slope (Shields and Kelly 1997, Brooks and Davis 1987). Territoriality also plays an important role in nest site selection with kingfishers’ nest sites evenly distributed along a suitable habitat range (Silver and Griffin 2009). Studies have conflicted on the average breeding territory size, with findings ranging from 0.4-1 nests per km in Silver and Griffin’s (2009) study to Cornwell’s (1963) findings of one nest per 2.1km. Kingfishers select for a tall, vertical bank to eliminate risk of flooding and improve predator avoidance (Brooks and Davis 1987). Selection of a bank with a uniform slope is also important for predator avoidance (Shields and Kelly 1997). Silver and Griffin (2009) found in their Connecticut based study that kingfishers are 1.4 times more likely to use a bank with every meter increase in bank height and 1.2 times more likely to use a bank with every degree of slope increase. While research in the northeastern United States has shown that individuals prefer a higher ratio of sand to clay (75:25) to ease excavation, soil composition in other nest locations show that the Belted Kingfisher may be more flexible in site selection in different regions of North America (Brooks and Davis 1987, Shields and Kelly 1997).

Nest & Nest Construction:

Nest cavities are composed of a narrow tunnel that’s typically one to two meters long terminating in a nest chamber (Fry 1992). The nest tunnel may incline or decline with sharp or shallow bends principally right before the nest chamber (Bent 1954, Cornwell 1963). The nest chamber is usually circular and varies in size (Bent 1954). Preliminary nest construction begins with exploratory stabs at a site from a hovering and perching position (Hendricks et al. 2013). Aerial ramming to excavate the site have been observed and documented in other members of the Alcedinidae family (Hendricks et al. 2013). Hendricks et al. (2013) has documented Belted Kingfishers engaging in this behavior as well. Hendricks’ study proposed that aerial ramming is utilized to excavate nests if the site does not have suitable places to perch and/or the substrate is too hard to hover and stab at. The remainder of excavation is done with a combination of the syndactyl foot digging and removing substrate with the beak (Bent 1954, Hendricks et al. 2013). Both male and female dig and participate in nest excavation and aerial ramming (Bent 1954, Hendricks et al. 2013). New nests are typically completed in less than two to three weeks (Harrison 1979). Nest sites can be used for multiple years and may be extended over the years but are sensitive to disturbances (Bent 1954, Cornwell 1963). Parental abandonment of nests was found to be the leading cause for reproductive failure in Belted Kingfishers (Bridge and Kelly 2013).

Eggs:

Between five and eight eggs are laid; most commonly between six and seven (Harrison 1979). The eggs are a smooth white, almost glossy and vary in shape from elliptical to a short oval (Harrison 1979). Eggs are typically laid one a day until the clutch is complete (Fry 1992). Cornwell (1963) observed that the eggs were strategically placed in a tight circle around one central egg. Both the male and female rotate incubating the eggs for 23-24 days (Fry 1992, Harrison 1979). Typically only one mate stays in the nest overnight while the other roosts close by or in an additional roosting tunnel (Cornwell 1963, Harrison 1979). Ectoparasite loads from nests are found to be heavier on female Belted Kingfishers confirming that females are the primary incubators and brooders (Boyd and Fry 1971). Only one brood is raised a year though additional nesting attempts can be made if initial attempts are disrupted (Bent 1954).

Young:

At hatching, the young are altricial – being born naked, blind, and helpless (Gill 2007). The average brood size is four, with birds hatching at one-day intervals (Fry 1992). This staggered hatching can result in brood reduction by giving older nestling an upper hand during feedings and resulting in the starvation of younger nestlings (Fry 1992, Gill 2007). Nestlings are mobile even before opening their eyes, and they can move around upright on tarsi that are heavily ridged with callus-like horny projections (Fry 1992, Cornwell 1963). Feathers begin to grow in during the second week, and juvenile plumage is completed by the fourth week (Bent 1954). Cornwell (1963) suggests that young kingfishers may keep the nest more sanitary by excreting in the same areas and covering these areas with substrate dug from the walls of the nest chamber. Young remain in the nest for 30-35 days (Fry 1992).

Fledging & Post-Nesting:

Typically before the first flight, the nestlings are starved for one to two days in order to motivate their fledging (Fry 1992). After first fledging, the parents have been observed to resume assisted feeding as the fledglings begin to fish by themselves (Bent 1954). Initial diving attempts by the young have high mortality rates (Fry 1992). The young may stay to help to defend their parent’s territory throughout the autumn (Davis 1982).

Life Span:

Currently, no studies exist that directly quantify life span of Belted Kingfishers (Kelly et al. 2009).

Mortality Rates:

Mortality rates have proved to be difficult to obtain due to the wide dispersal of Belted Kingfishers after the breeding season (Kelly et al. 2009). Shields and Kelly (1997) reported only a 20% return on banded adult Kingfishers to breeding territories after one year. Bridge and Kelly’s (2013) study found only a 2% return of nestlings to the original territory and a 27% adult return. It is hypothesized that these low numbers are to high rates mortality and dispersal (Bridge and Kelly 2013, Kelly et al. 2009).

Current Status:

The International Union of Conservation Network (2012) has listed the Belted Kingfisher as a species of least concern. The IUCN defines a species of least concern to have a large population and range whose habitat is currently not subjected to a large decline in size or quality with a less than thirty percent decline in population over the past three generations or thirty year. While Belted Kingfishers are not considered to be at risk globally, their ecology and biology make them useful environmental indicators (Birdlife International 2012, Evers et al. 2005).

Disease & Parasites:

Due to the diet and nesting habits of Belted Kingfishers, they are highly susceptible to parasitism (Boyd and Fry 1971). Most detrimental and common are ectoparasites and helminthes gleaned from nesting habits and prey respectively (Boyd and Fry 1971). Helminthes are a group of intestinal parasites that include the phyla classes Nematodes (roundworms), Trematoda (flukes), Cestodas (tapeworms), and Monogenea (flatworms). Ectoparasites are parasites that can survive outside of a host like fleas. The life cycles of most helminthes involve an asexual phase in an intermediate host (snail), water transfer to a secondary intermediate host (fish), and finally consumption by the definitive host (kingfisher) for completion of parasite sexual development (Lane and Morris 2000). Parasitized intermediate fish hosts have shown increased preference for shoaling positions to the front and sides of the group, possibly increasing predator risk by the kingfisher (Ward et al. 2002). The rates of occurrence of helminth parasites are reflected in the amount of ingested intermediate hosts in the diet such as fish and frogs (Muzzell et al. 2011). Helminths have been found to cause anemia, eye congestion, and heptic duct blockage (Boyd and Fry 1971). Due to their non-social behavior and frequent washes, Belted Kingfishers have low levels of mites and lice (Boyd and Fry 1971). Current knowledge of kingfisher parasite species diversity is based on data from northeastern North America; parasite species diversity is expected to increase with study location expansion (Muzzel et al. 2011).

Predators:

The main predators for Belted Kingfishers are the Cooper’s, sharp-shinned, and red-tailed hawks (Bent 1954). Predation is not cited as a serious threat to adults; young fledglings are at the greatest risk of predation (Cornwell 1963). Snakes, minks, and skunks have been reported as nestling predators (Bent 1954).

Habitat Loss:

Mažeika et al. (2006) has linked reproductive success to habitat quality for Belted Kingfishers, finding that prey and nesting sites are sensitive to habitat changes. Human development and pollution of riverine, estuarine, and coastal systems can negatively impact fish populations creating a scarcity of food directly affecting breeding efforts (Mažeika et al. 2006, Davis 1982). The availability of stopover sites during migration is also a concern (Hamas, 2005). Belted Kingfishers have been found to utilize both undeveloped and developed shoreline but are hindered by tall, emergent vegetation (Traut and Hostetler 2003).

Pollutants:

Belted Kingfishers are high trophic level predators in the ecosystems they occupy (Steinmetz et al. 2003). Their food web positioning, longer life spans, and high metabolism allow for a bioaccumulation of many aquatic toxins (Zamani-Ahmadmahmoodi et al. 2009, Bridges and Kelly 2013). As a result, Belted Kingfishers are considered an important environmental indicator species for mercury, PCBs, PCDFs, and PCDDs (Evers et al. 2005, Bridge and Kelly 2013, Seston et al. 2012). They are particularly useful as a standard indicator species as populations are widespread and found across all types of waterways both fresh and marine (Evers et al. 2005). Mercury in particular is readily bioaccumulated in Belted Kingfishers as it persists well in aquatic systems and is easily uptaken by proteins in the body (Zamani-Ahmadmahmoodi et al. 2009). Mercury has been known to affect the immune, endocrine, and reproductive systems of wild birds (Scheuhammer et al. 2007). Birds can lessen the body load of mercury by transferring it to feathers during the molt, since mercury has a high affinity for keratin (Evers et al. 2005, Zamani-Ahmadmahmoodi et al. 2009). However higher mercury levels in Belted Kingfishers have been found to correspond to a more impure white coloration on the breast and brighter plumage coloration specifically in blue feathers (White and Cristol 2014). This is a result of a decrease in melanin due to mercury contamination and may impact mate selection possibly resulting in reduced fitness (White & Cristol 2014).

Climate Change:

Decreases in the pH of fresh water ecosystems, such as lakes, has been found to correlate to an increase in mercury levels in fish – the main prey of Belted Kingfishers (Evers et al. 2005).

Belted Kingfishers were observed in Thurston and Pacific County in Washington State during late November 2014. Quantitative data on foraging time between dives, dive frequency and height, hover frequency and height, and dive angle was gathered. Qualitative data was gathered on the behavior of Belted Kingfishers during the late fall including territoriality. Written summaries of observations, descriptive statistics, and conclusions are located below.

Summary of Observations from November 17, 2014:

Observations made from viewpoint on Percival Cove, Olympia WA

Observed from 10:00 – 14:30

No precipitation or cloud coverage throughout observation period. Wind was very light, less than five mph, and caused no surface ripples. Temperature ranged from 45-50 degrees Fahrenheit. This was one of the first longer stretches of cold weather this fall. Ice covered the southern third of Percival Cove stretching from east to western shore. Ice was thick enough to support river otters walking across and presumably prohibit Belted Kingfishers from fishing in that area. The northern third of Percival Cove was sunlit throughout the observation period while the rest of the cove was shadowed. Belted Kingfishers were only observed in the sunlit portion of the cove but were observed to fly through the shadowed portion occasionally.

Three Belted Kingfishers (named A, B, and C) were observed during time period with the main focus on kingfisher “B”. Due to distance, sun direction, and orientation sex was not accurately determined. Some degree of territoriality was observed between the three kingfishers. When kingfisher “C” approached the edge of “B’s” territory, “B” would begin calling loudly and swoop at “C” until “C” dispersed. “A” was observed doing similar behavior to “B”. “B” had the most defined territory following the shoreline from the WSW edge of “C’s” territory at 47.0337637N, 122.9127659W to the ENE edge of “A’s” territory at 47.0337294N, 122.9135186W. The other limits of “A” and “C’s” territory were not observed.

All of the kingfishers observed tended to fly very low over the water, within one meter of the surface. Small movements from perches greater than one or two meters apart would result in a low swoop over the water. It was unclear if perhaps this was an aborted diving attempt, but it did not resemble a hovering attempt. Since the head remained erect and not looking down during these small swoops it could be reasoned that this was not an aborted diving or hovering attempt.

The majority of the time the kingfishers remained perched in one stationary perch. The majority of the perches were overhanging water with little to no foliage on them. Perches ranged from a spruce, red alders, a big leaf maple, and other dead deciduous trees – most likely red alders. The stoutness of the perch varied from smaller, thin branch ends to a thick piling stump. Perch heights above the water surface ranged from 0.9m to 6.5m as measured by an Opti-Logic Insight 400 LH range finder. The shoreline was relatively free of vegetation and the water in the cove clear of visible vegetation appearing to have a muddy bottom similar to that of Capitol Lake.

Preening was only observed for a few minutes. The majority of the time the kingfishers were perched with their heads tilted slightly downwards assumedly searching for prey below and around their perch. While perched they would change their orientation by moving around on perch. It did not appear that any orientation was favored in regards to sun direction but this may be an area of further study. Time spent searching ranged from 32 seconds to 30 minutes and 24 seconds. Usually the kingfisher would change perches during the searching time period, the maximum time that “B” changed perches was seven times.

Diving was observed mainly at oblique angles – greater than 45 degrees. There was one instance of a straight vertical dive off an angled perch and two instances of dives made at acute angles – less than 45 degrees. Hovering was only observed once, one meter above the surface, but the bird did not dive. “B” was typically successful with dives; catching prey nine out of the twelve times during the period dives were recorded. “B” was observed banging a small fish three times on the perch before being swallowed. After dives, successful or not, kingfishers would typically land on a perch that was very close to the water surface, at most one meter above before relocating to another higher perch. On this lower perch there would be a series of body shakes and wiping of the beak onto the branch or perch several times. The prey would be consumed on the lower perch usually.

Of the three birds observed, “A” was the most vocal and traveled the most, often disappearing out of sight onto southern side of the cove or into the wooded area surrounding the north side of the cove. “A” could be heard repeatedly calling when out of sight on the southern side of the lake. “C” appeared latest in the day and remained perched on the edge of “B’s” territory for over an hour with no dives or movements made before leaving and not coming into sight again. “B” stayed in sight the majority of the observation period, leaving for a few minutes in the woods but reappearing. When the sunlight started to wane on the northern side of the cove all three birds went out of sight and did not come into view again.

Summary of Observations on November 20, 2014

Observations were made from viewing platform on boardwalk at Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge

Observations made between 10:00 until 14:00, not consistently

During observation period, cloud coverage was at 100% and there was occasional light rain. Temperature varied between 47 and 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Wind was about five miles per hour from the east, noticeable on the boardwalk. A 6’3” low tide occurred at 9:57 and a 13’3” high tide at 15:17.

In the late morning around low tide, spent approximately an hour searching for Belted Kingfisher on the boardwalk but no sighting or hearing of one along the boardwalk. Walked back towards the main pond behind the visitor center but did not hear nor see one.

In early afternoon made way back out to boardwalk to the first viewing platform at the beginning of the boardwalk. From viewpoint observed a female Belted Kingfisher, identifiable by distinct secondary rufous chest band and rufous coloration on sides. Tide was mid-flood. The kingfisher did not dive during observation period but remained perched on a small, dead, deciduous tree slightly overhanging the northern tidal flat fork of McAllister Creek. She was perched approximately two meters above water surface and preened her chest with her beak occasionally. Water underneath appeared to be moving and was not clear. Substrate bottom was muddy. She did not dive but did fly low – less than one meter – above surface level to change to another perch, similar in height and type to previous one.

Possibly unconnected/connected, Belted Kingfisher’s appearance coincided with the cessation of nearby duck hunting. It is unknown if Belted Kingfisher’s fish dependent upon tidal cycles, which may explain appearance at a different stage in the tide.

Summary of Observations on November 22nd, 2014

Observations made from viewpoint on Percival Cove, Olympia WA

Observed from 13:00-15:00

Temperature remained relatively constant during observation period, staying around 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Wind speed started at less than ten miles per hour but grew over observation period until about 11 miles per hour from the SW. Wind tended to be gusty, blowing hard at times then backing off causing intermittent periods of slight chop on the water. Periods between gusts were longer at the beginning of the afternoon. There was no ice on the water. There was no precipitation during the afternoon, but it had rained lightly earlier in the day. Cloud coverage was at 20% at 13:00, covering only the SW portion of the sky but gradually grew to over 40% moving from west to east until end of observation period. Cloud coverage increased the most between 14:30 and 14:45. Northern portion of the cove remained sunlit until cloud coverage started to increase and wind picked up. The water appeared to be higher than when observations were made on November 17th, 2014. It is unsure if drainage of Capital Lake or tides influences water levels in Percival Cove.

Did not observe Belted Kingfishers for a long while but could hear calls occasionally further off. It was unsure of what direction but sounded mainly north. Checks at northern locations such as the viewing boardwalk by Bayview’s Thriftway yielded no sightings. There is a small creek (Percival Creek) that runs southwest from northern Percival Cove behind the lake and it is possible that the kingfisher may have been located there where calls could be heard but the bird couldn’t be seen. It was not determined if it was one or multiple individuals that were calling.

Eventually a Belted Kingfisher (unable to determine sex, too far away) flew in from the northern direction out of the woods. The kingfisher perched in “B’s” territory from November 17th possibly identifying it as “B”. During observations it perched in only two places, one at 1.5 meters above water and another at 3.4 meters. It appeared to be searching for food but did not dive nor hover. It called when it approached the perch for the first time coming from the woods and called again when it left and flew back northwards into the woods. The leaving occurred at the same time the northern portion of the lake where it was perched became shadowed with increasing cloud coverage and increasing wind speeds and gust frequencies.

Summary of Observations on November 23nd, 2014

Sited Observations were made from viewpoint on Percival Cove, Olympia WA

Other observations made from Bayview, upper and lower sections of Tumwater Falls Historical Park, and Capitol Lake’s interpretive park.

Observed from 10:00-15:00

Over the course of the day temperature did rise from 47 to 53 degrees Fahrenheit. There was occasional rain in the morning that varied from light to heavy. Cloud coverage was at 80% consistently with breaks mainly in the north. Wind was less than ten miles per hour from the south, stronger in the morning. Low tide for Budd Inlet was at 12:12 at 7.10’, high tide was at 16:56 at 14.21’.

Based on previous observations, Belted Kingfishers were observed more at Percival Cove in the early afternoon when temperature for the day had risen and sunlight covered the northern portion of the cove. Based on personal observations and eBird (2014) data, sightings of Belted Kingfishers had occurred up and down the Deschutes River drainage and attempts were made to sight Belted Kingfishers there during the morning hours. It was thought that perhaps “A”, “B”, and “C” may be located elsewhere along the river drainage during these hours – though there was no way to positively identify them as they are not banded. Five sites were identified to visit during the observation hours moving from northern to southern (more upstream) positions starting at Bayview, Percival Cove, Capitol Lake’s viewing platform, then lower and upper sections of Tumwater Falls Historical Park. Observations at each sight included watching and listening for Belted Kingfisher and making notes on general conditions for 15-30 minutes before moving to next site. At the south-most site, began working northwards again. Because Belted Kingfishers have been observed at all these sites, their absence during observations is noteworthy. It was hoped that even if a Belted Kingfisher was not spotted perhaps there may environmental cues that reveal why they were not there.

With the exception of Percival Cove, most sites did not have very many overhanging perches. The most lacking was Bayview where the open, deeper estuarine waters were very clear but had no overhanging foliage to perch and hunt directly from. Personal past observations have seen the bird across the waterway on the west side of the inlet perched on signs and flying out from underneath the fourth avenue bridge. Water at Bayview was fairly still, though moving out with the tide.

The fastest moving water, and shallowest was at the upper portion of Tumwater Falls Historical Park where riffles were obvious. A previous paper by Davis (1982) had mentioned the desirability of riffles during nesting season but no sightings. The majority of these spots were fairly shaded during the late morning hours during the winter; perhaps this played a role in determining where the kingfishers were. Kelly’s (1998) paper on winter habits of Belted Kingfisher’s found that they were most active in the afternoon and spent a majority of the time perched in sunlit areas.

The first sighting of a Belted Kingfisher was made at 12:20 at Percival Cove. Since so much of the morning had not resulted in a sighting it was determined that it would be better to stay observe at Percival Cove until the bird departed. At this point the northern portion of the cove was much more sunlit and it was warmer with less wind and no rain. It appeared to be Belted Kingfisher “A” based on the location of his perch in “A’s” territory. The bird was calling repeatedly with some short breaks for 18 minutes. Calling ceased when two other Belted Kingfishers flew across the cove from the southeastern shadowed portion and straight into the northern woods. The two were not seen again during the rest of the observation period.

During the observation period, the kingfisher was perched primarily in large alder trees slightly overhanging surface water, but not as advantageously as in “B’s” territory from November 17th, 2014. “A” never ventured into “B’s” territory even though it was more sunlit, had more overhang, and there was no other kingfisher in sight. Perch heights in the red alders varied from 6-6.5m above surface level. Once, the kingfisher flew across pond and back to perch without landing on south side of cove while calling. Occasionally the kingfisher would disappear further west into the woods but would return from the same direction into similar perches. On these higher perches the bird made frequent tail flicks, appearing to be a balancing aide but may have been behavioral – had not observed before on other kingfishers.

“A” made one vertical dive from 8m above the surface and was unsuccessful but rose rapidly from the water to 0.3m and dove again less than a meter away from original dive site then perched nearby a meter off the water. Neither dive was successful. The bird remained on a low perch for more than ten minutes doing rapid body shakes, tail flicks, and scraping beak against side of perch. Eventually the bird flew very high into a red alder (approximately 6m) and remained perched there for over 45 minutes occasionally preening. As wind began to pick up again the bird left and flew northwards into the woods.

Summary of Observations on November 28, 2014

Observations made by edge of greenbelt in Vandalia neighborhood Ilwaco, Washington

The greenbelt in back of neighborhoods consists of a smaller pond with many overhanging willow trees, tall cattails, and some hardhack. It may be very slightly influenced by the tides, as the water is fed into a creek nearby that is heavily influenced by Baker’s Bay tides. Many species of ducks opportunistically use this pond. It is unsure if there are any fish, though the creek itself does have some bivalves and small fish. It is fairly shallow and can become heavily vegetated during summer months. A male Belted Kingfisher is often observed perched in a two-meter tall dead willow tree on edge of pond. He was perched for approximately ten minutes before calling twice and flying in a northeastern direction. Temperature was around 55 degrees Fahrenheit with light wind from the WSW. Overcast with very little rain. Did not observe him during periodic checks the remainder of day.

Summary of Observations on November 29,2014

Observations were made from jetty at Waikiki Beach, Washington

Observations made from 13:00 – 15:00

Low tide was at 13:06 at 2.6’. Temperature was around a chilly 40 degrees Fahrenheit and wind was mainly from the northeast, being blocking in the cove. There was a large southerly swell that resulted in a high amount of chop and easterly winds created many white caps in the channel. The jetty that extends westward is made of large boulders with many dead logs and debris thrown up on it. The western side of the cove is bordered by tall rock cliffs with a few outcropping that are utilized by cormorants for nest and roosting sites. A Belted Kingfisher sighting was not expected here but it was seen swooping two meters above the water surface outside the breakers in the cove moving between the jetty and the cliffs. The distance between the two is approximately 30-40 meters. The bird did not swoop very low over water as had been observed presumably because of the large waves and wind chop.

It was never observed diving and was difficult to track on the cliff. Observer was unsure of where on the cliff and jetty it rested. There is a small pool on the northern side of the jetty that it may have been fishing in but it seems unlikely since the tide was low and there are not typically prey items in the temporary pools. Due to the roughness and depth of water it seems unlikely that it was foraging but it was unclear as to what it was doing. It made multiple passes, each lasting approximately five minutes and would disappear on either side for up to fifteen minutes. The range of habitats that Belted Kingfishers will visit is astounding.

Results:

Kingfishers are notoriously difficult to study due to their large territory ranges and relative rarity. Collecting data on diving and foraging times was difficult which limited the number of quantifiable observations as seen in Table 1 below. Data was collected on the amount of searching time before a dive, the number of times a kingfisher changed perches during the searching time, the height of perch that was dove from, if a hovering event occurred and at what height above the water, the dive angle, and if the dive was successful.

Quantified observations were used only from Percival Cove in Olympia, WA on November 17th and 23rd during the early afternoon. This was due to the location’s ease of observing for longer periods of time and consistency of the Belted Kingfisher’s presence. Though general cloud coverage differed between the days, the area of the cove that the kingfishers were observed was completely sunlit both days and free from wind. It is possible that the slightly differing conditions may have caused changes in behavior but the small sample size hinders any further analysis.

Mean searching time per dive was 9.37±12.10 minutes (n=17). The mean number of perch changes between per dive was 2.59±1.82 (n=17). The mean height of the diving perch was 4.41±2.11 meters (n=17). Standard deviations of these numbers were high as there were a low number of useable observations (n=17).

Hovering events occurred only 12% of the time; no dives followed any hover event. All hovering events occurred one meter above water surface. Hovering was classified as its own event even when no dive followed as it was considered an aborted dive/foraging attempt. Though some then may argue that a perch change may also be considered an aborted dive, per personal observation though perch changes appeared to not be aborted dives. This is because perch changes occurred within a one to two meter radius of each other and rarely involved any swooping behavior towards the water surface.

Diving events were made at some angle from the perch to the water surface. Oblique angles occurred 67% of the time, acute angles 20% of the time, and vertical angles 13% of the time. Dives were found to be successful, meaning a prey was captured, 67% of the time.

Table 1: Foraging behavior of Belted Kingfisher “B” on November 17th and and Belted Kingfisher “A” on November 23rd, 2014. Types of dives are classified as oblique (dive angle greater than 45 degrees), acute (dive angles less than 45 degree), and vertical (no angle to dive). Total observations n = 17.

Conclusions:

General observations on foraging times were mainly in agreement with Kelly’s (1998a) paper on the behavior of Belted Kingfishers during winter. Kelly (1998a) reported that Belted Kingfishers spent 98.7% of their time perched during the late morning to early afternoon hours and 98.9% during mid-afternoon hours. Though these observations (Table 1) were not able to directly quantify percentage of time perched, Belted Kingfishers were found to be perching the vast majority of the time with infrequent, short flight durations. Kelly (1998a) reported perch durations that overlapped observations from Table 1 (8.5±1.4 minutes versus 9.37±12.10 minutes), expanded observations are needed to reinforce any agreement between these observations and Kelly’s.

As reported in Fry (1992), the kingfishers were found to utilize oblique dives a majority of the time. Diving heights of 4.41±2.11 meters (n=17) were within the range that Fry (1992) reports. As dives were made from perches during these observations it may be that the availability of perches determines the diving height, not a particular diving height preference by the individual. Perch changes during the searching time were frequent with the mean 2.59±1.82 (n=17). It is assumed that perch changes were made to better foraging efforts but further research is needed.

Hover frequency was not reported in any sources that were reviewed, so it is uncertain if the low frequency is common or if hovering is dependent on habitat. Future studies could possibly compare the frequency of hovering between sites with varying numbers of available overhanging perch sites.

BirdLife International (2012). Megaceryle alcyon. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3.

Boyd, E.M. and A.E. Fry (1971). Metazoan parasites of the eastern belted kingfisher, Megaceryle alcyon alcyon. The Journal of Parasitology 57(1):150-156.

Bent, A.C. (1954). Life histories of North American cuckoos, goatsuckers, hummingbirds, and their allies. U.S. National Museum Bulletin 176:111-130.

Bridge, E.S. and J.F. Kelly (2013). Reproductive success of belted kingfishers on the upper Hudson River. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 32(8):xx-xx.

Brooks, R.P. and W.J. Davis (1987). Habitat selection by breeding belted kingfishers (Ceryle alycon). American Midland Naturalist 117: 63-70.

Cornwell G.W. (1963). Observations on the breeding biology and behavior of a nesting population of belted kingfishers. The Condor 65(5):426-431.

Davis, W.J. (1986). Acoustic recognition in the belted kingfisher: cardiac response to playback vocalizations. The Condor 88(4):505-512.

Davis W.J. (1982). Territory size in Megaceryle alcyon along a stream habitat. The Auk 99(2):353-362.

eBird (2014). eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application].

Evers, D.C., N.M. Burgess, L. Champoux, B. Hoskins, A. Major, W.M. Goodale, R.J. Taylor, R. Poppenga, and T. Daigle (2005). Patterns of interpretation of mercury exposure in freshwater avian communities in northeastern North America. Ecotoxicology 14:193-221.

Fry, C.H. (1992). Kingfishers, bee-eaters, and rollers. Princeton University Press, NJ.

Gill, F.B. (2007). Ornithology, third edition. W.H. Freeman and Company, NY.

Hamas, M.J. (2005). Territorial behavior in belted kingfishers, Ceryle alcyon, during fall migration. Canadian Field Naturalist 119(2):293-294.

Harrison, H.H. (1979). A field guide to western birds’ nests. Houghton Mifflin Company, NY.

Hendricks, P., D. Richie, and L.M. Hendricks (2013). Aerial ramming, a burrow excavation behavior by belted kingfishers, with a review of its occurrence among the Alcedinidae. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 125(1):197-201.

Kelly, J.F., E.S. Bridge, and M.J. Hamas (2009). Belted Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Kelly, J.F. (1998). Behavior and energy budgets of belted kingfishers in winter. Journal of Field Ornithology 69(1):75-84.

Kelly, J.F. (1998). Latitudinal variation in sex ratios of belted kingfishers. Journal of Field Ornithololy 69(3):386-390.

Kelly, J.F. (1996). Effects of substrate on prey use by belted kingfishers (Ceryle alcyon): a test of the prey abundance-availability assumption. Canadian Journal of Zoology 74:693-697.

Lane, R.L. and J.E. Morris (2000). Biology, prevention, and effects of common grubs (digenetic trematodes) in freshwater fish. USDA Technical Bulletin Series 115.

Mažeika, S., P. Sullivan, M.C. Watzin, and W.C. Hession (2006). Differences in the reproductive ecology of belted kingfishers (Ceryle alcyon) across streams with varying geomorphology and habitat quality. Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology 29(3):258-270.

Muzzall, P.M., V. Cook, and D.J. Sweet (2011) Helminths of belted kingfishers, Megaceryle alycon Linnaeus 1758, from a fish hatchery in Ohio, U.S.A. Comparative Parasitology 78(2):367-372.

Procotor, N.S. and P.J. Lynch (1993). Manual of Ornithology. Yale University Press, CT.

Scheuhammer, A.M. M.W. Meyer, M.B. Sandheinrich, and M.W. Murray (2007). Effects of environmental methylmercury on the health of wild birds, mammals, and fish. Ambio 36(1):12-18.

Seston, R.M., J.P. Giesy, T.B. Fredricsk, D. L. Tazelaar, S.J. Coefield, P.W. Bradley, S. A. Roark, J.L. Newsted, D.P. Kay, and M. J. Zwiernik (2012). Dietary and tissue based exposure of belted kingfisher to PCDFs and PCDDs in the Tittabawassee River floodplain, Midland, MI, USA. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 31(5): 1158-1168.

Shields, S.J., and J.F. Kelly (1997). Nest-site selection by belted kingfishers (Ceryle alcyon) in Colorado. American Midland Naturalist 137:401-403.

Sibley, D.A. (2001).The Sibley guide to birds. Alfred A. Knopf, NY.

Silver, M. and C.R. Griffin (2009). Nesting Habitat Characteristics of bank swallows and belted kingfishers on the Connecticut River. Northeastern Naturalist 16(4):519-534.

Steinmetz, J., S.L. Kohler, and D.A. Soluk (2003). Birds are overlooked top predators in aquatic food webs. Ecology 84(5):1324-1328.

Traut, A.H. and M.E. Hostetler (2003). Urban lakes and waterbirds: effects of shoreline development on avian distribution. Landscape and Urban Planning 69:69-85.

Ward, A.J.W., D.J. Hoare, I.D. Couzin, M. Broom, and J. Krause (2002). The effects of parasitism and body length on positioning within wild fish shoals. Journal of Animal Ecology 71:10-14.

White, A.E. and D.A. Cristol (2014). Plumage coloration in belted kingfishers (Megaceryle alcyon) at a mercury-contaminated river. Waterbirds 37(2):144-152.

Zamani-Ahmadmahmoodi R., A. Esmaili-Sari , and S.M. Ghasempouri (2009). Mercury levels in selected tissues of three kingfisher species; Ceryle rudis, Alcedo atthis, and Halcyon smyrnensi, from Shadegan marshes of Iran. Ecotoxicology 18:319-324.

Jacqueline Kociubuk is a B.S. graduate of TESC as of December 19th, 2014 with a major emphasis in biology and a minor emphasis in chemistry. She has worked and studied primarily in the marine sciences.

Leave a Reply