Order: Passeriformes

Family: Troglodytidae

Genus: Thryomanes

Species: Thryomanes bewickii

Introduction

In 1821, J.J. Audubon collected the first official Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii) specimen in Louisiana. The name “Bewick’s Wren” was chosen by Audubon after friend, British engraver and natural history author, Thomas Bewick (Kennedy and White 2013).

Bewick’s Wrens are about 13 cm long and have a mass of roughly 11g (Kennedy and White 2013). The length of the slightly down-curved bill is nearly equivalent to head diameter. Plumage is counter-shaded with a brown dorsal side and pale-gray ventral side, which gets progressively darker from the throat to the belly and flanks. Some of the gray plumage extends from the breast up to the auricular. There is a distinctive white supercilium. The long tail is barred both on top and on the undertail coverts, and is wagged incessantly. Barring is also present on the wings. Tarsi and feet are grayish in color and feet are anisodactyl.

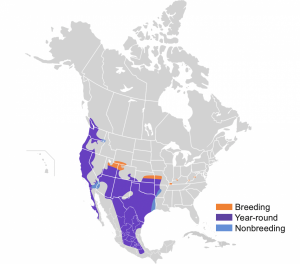

The Bewick’s Wren is native to North America. In the west, year-round range extends from Southern British Columbia through Western Washington, Western Oregon, Northern and Central California, Western Nevada and into coastal Baja Peninsula. In Southwestern/South-central US, year-round range includes Southern Utah, most of Arizona, New Mexico, most of Texas, Oklahoma, Southern Colorado, Southern Kansas, Southwestern Missouri, and Western Arkansas, and extending far into central Mexico. Northeastern Utah, Southern Wyoming, Northeastern Kansas, Central Missouri make up the majority of the breeding range. There are three relatively small non-breeding ranges in Southeastern Washington/Northeastern Oregon/Western Idaho, Southern California/Western Arizona, and a band stretching from Western Arkansas, through Eastern Texas, to the Gulf of Mexico (Kennedy and White 2013).

Kennedy, E. D. and D. W. White (2013). Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.2173/bna.315.Cephas [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thryomanes_bewickii_map.svg

Bewick’s Wrens are secondary cavity nesting birds that will nest in snags, nest boxes, building crevices and other natural and man made structures (Tomasevic & Marzluff 2016). They are considered a synanthropic, early-seral species (Kennedy & White 1996) that can inhabit a wide variety of anthropogenically modified landscapes, including forest edges, parks, fields, and neighborhoods (Farwell & Marzluff 2013). Although breeding habitat and specific vegetation is variable depending on climate, a heterogeneous combination of scrubland/chaparral and open area is the common theme (Kennedy & White 2013). Harrod and Green (2018) showed that shrub-land perimeter to area ratio among box-nesting Bewick’s Wrens in central Texas, US was negatively correlated with nest success, suggesting that patch size and shape are important variables. Nests further from trees and in areas not exposed to large bands of edge habitat were more successful. The authors infer that this trend is probably related to edge effects and associated likelihood of predation.

Mainly insectivorous, but known to eat very small amounts plant material in winter months (Beal 1907), the Bewick’s Wren feeds mostly on larvae and mature arthropods (Kennedy & White 2013). With its down-curved bill, it gleans small insects from low twigs and leaves of all vegetation types within its habitat. It will also forage in leaf litter and the furrowed bark of larger trees (Miller 1941). According to the inspection of the contents of 146 stomachs taken across all months of an entire year, Hemiptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, and Lepidoptera make up 81% of the Bewick’s Wren’s overall diet. The remaining 19% is made up of other types of insects and spiders and <3% plant material (Beal 1907). In early spring, western pairs have been known to stratify foraging effort, where males tend to stay in the brush and and trees and females forage on the ground. After nesting, sexual foraging stratification is ceased (Miller 1941).

Becky Matsubara from El Sobrante, California [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bewick%27s_Wren_(39098681115).jpg#/media/File:Bewick%27s_Wren_(39098681115).jpg

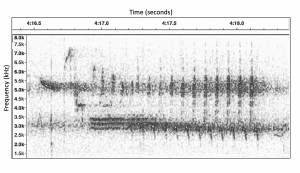

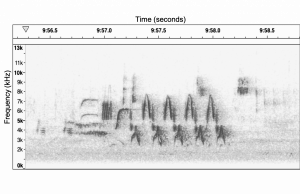

Singing is done by males only. They will often sing in the open on the tips of branches in the early spring before mating (Miller 1941).Territorial songs are usually a combination of 3–5 phrases, including up to 2 rhythmically succinct trills. Initial notes can be easily mistaken for those of the Song Sparrow’s song. Generally, there are short buzzy notes just before the trill, which are sometimes vocalized independently (Miller 1941). The final syllable, which sounds similar to the trill of the Eastern Towhee song, is not always included (Kennedy & White 2013).

Songs are variable among populations. Repertoires of individuals can be as high as 22 songs, and include up to 63 different phrase types (Kroodsma 1985). Song variability among individuals is often greater in populations located in areas that support fewer sympatric species (Kroodsma 1985). Peak frequency of songs can range from 3.3–4.1kHz, and songs over 3 seconds in length are considered to be notably longer than average (Kennedy & White 2013). Using a dataset collected from the songs of 52 passerine species, including the Bewick’s Wren, Cardoso and Price (2010) found that frequency was significantly different among communities of differing habitat but not continents, which they infer is due to the behavior of sound waves within the variable environments. Song frequency variation was negatively correlated with body size (large bodies = lower frequencies).

Anti-predator calls measured by Yorzinski and Patricelli (2010) at the Animal Communication Laboratory in Davis, California had a mean peak amplitude of 59.8 db, a mean peak frequency of 7.1kHz, and a mean duration of 0.80s.

Spectrogram of Bewick’s Wren Song. Recorded by Philip Hyde, February 20, 2019 at Mission Creek Park, Olympia, WA 98506.

“Bewick’s Wren Song” Birds: Inside and Out 2019 by Philip Hyde

Spectrogram of Bewick’s Wren Song 2. Recorded by Philip Hyde, February 20, 2019 at Mission Creek Park, Olympia, WA 98506.

“Bewick’s Wren Song 2” Birds: Inside and Out 2019 by Philip Hyde

Foraging is done intensively, with a pecking rate of ~1 peck per second, while making small jumps between various forms of low vegetation. It is not uncommon to see a Bewick’s Wren hanging upside-down from branches while gleaning insects. This intensive foraging is usually in relatively small areas within an individuals own territory. The Bewick’s Wren uses its bill to glean insects from twigs and furrowed bark, and flip over leaf litter. Sometimes it will repeatedly wipe its bill across twigs obsessively after successful depredation (Miller 1941).

Territory size in Oregon populations ranged from 2.0—3.8 ha, depending on physical habitat characteristics, habitat saturation, and overlap with the House Wren (Kroodsma 1973). Bewick’s Wren’s will make an effort to defend their territories from House Wren’s by singing and pursuing, but these attempts are likely unsuccessful (Root 1969). Ultimately, House Wrens will destroy the nests and eggs of Bewick’s Wren (Kennedy and White 2013). Kennedy and White 1996 observed 26 of 71 or 37% of Bewick’s Wren eggs were removed by House Wrens, in Kansas. The literature suggests that this aggression between the two wren species is significantly more severe in eastern states of the US (Root 1969, Kennedy and White 1996). Information regarding the reasons behind the more successful coexistence of western populations is sparse, but Odum and Johnston (1951) have pointed out that post-agricultural succession in eastern states has lead to the expansion of the House Wren’s range.

Mating strategy is almost purely monogamous, although a very small number of exceptions have been reported. Both males and females participate in nest building and forage together until incubation, at which point the male assumes primary foraging duty. Nests are built inside secondary cavities usually no more than 10 ft above the ground. Materials used for the nest are dependent upon the vegetation and other biota that are specific to a particular region. In some cases, reptilian skins have been used as nesting material, but primarily nests consist of leaves, twigs, bits of fern and other vegetation, as well as feathers and mammal fur. Shapes range from cup – shelf – dome. (Miller 1941, Kennedy and White 2013). Some pairs are established in the Pacific Northwest as early as February, and others remain paired throughout winter (Miller 1941, Kroodsma 1972). Bewick’s Wrens generally have up to 2 successful broods per year (Kroodsma 1973). There are no known cases of extra pair copulation.

Eggs are oval/rounded and speckled with spots that range in hue from reddish brown to purplish on an otherwise white shell. Clutch size is, on average, 5-6 eggs. Hatchlings are altricial. Both parents participate in feeding. Fledglings will leave the nest 14-16 days after hatching (Kennedy and White 2013).

Beal, F. E. (1907). Birds of California in relation to the fruit industry. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

Cardoso, G.C. & Price, T.D. (2010). Community convergence in bird song. Evolutionary Ecology, 24 (2) 447-461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-009-9317-1

Farwell L.S., & Marzluff J.M. (2013). A new bully on the block: Does urbanization promote Bewick’s wren (Thryomanes bewickii) aggressive exclusion of Pacific Wrens (Troglodytes pacificus). Biological Conservation, 161 (1), 128-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.03.017

Harrod, S., & Clay Green, M. (2018). Effects of class-level-vegetation characteristics on nesting success of Bewick’s Wrens. Southeastern Naturalist, 17 (3), 381-395. https://doi.org/10.1656/058.017.0302

Jardine L.E., Hosford A..N, Legg S.A., Stancampiano A.J. (2016). Habitat Selection, Nest Box Usage, and Reproductive Success of Secondary Cavity Nesting Birds in a Semirural Setting. Oklahoma Academy of Science, 96, 101-108. Retrieved from http://ojs.library.okstate.edu/osu/index.php/OAS/article/view/7210/6643

Kennedy, E., & White, D. (1996). Interference Competition from House Wrens as a Factor in the Decline of Bewick’s Wrens. Conservation Biology, 10(1), 281-284. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/stable/2386963

Kennedy E.D., & White D.W. (2013). Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii). Birds of North America. Retrieved from https://birdsna-org/Species-Account/bna/species/bewwre

Kroodsma, D. (1972). Bigamy in the Bewick’s Wren? The Auk, 89 (1), 185-187. doi:10.2307/4084072

Kroodsma, D. E. (1973). Coexistence of Bewick’s Wrens and House Wrens in Oregon. Auk, 90, 341-352. https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v090n02/p0341-p0352.pdf

Kroodsma, D. (1985). Geographic Variation in Songs of the Bewick’s Wren: A Search for Correlations with Avifaunal Complexity. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 16 (2), 143-150. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/stable/4599758

Miller, E. V. (1941). Behavior of the Bewick Wren. Condor, 43 (2), 81-99. https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/condor/v043n02/p0081-p0099.pdfRoot, R. (1969).

Odum, E., & Johnston, D. (1951). The House Wren Breeding in Georgia: An Analysis of a Range Extension. The Auk, 68 (3), 357-366. doi:10.2307/4080983

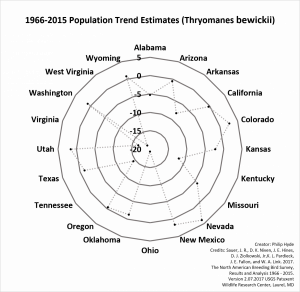

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. (2017). The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2015. Version 2.07.2017 USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD

Root, R. (1969). Interspecific Territoriality between Bewick’s and House Wrens. The Auk, 86 (1), 125-127. doi:10.2307/4083546

Tomasevic J.A., & Marzluff J.M. (2017). Cavity nesting birds along an urban-wildland gradient: is human facilitation structuring the bird community? Urban Ecosystems, 20 (2), 435-448. https://doi-org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s11252-016-0605-6

Yorzinski, J.L., & Patricelli, G.L. (2009) Birds adjust acoustic directionality to beam their antipredator calls to predators and conspecifics. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277 (1683) 923-932. http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1519

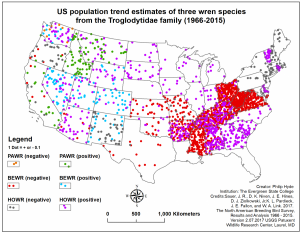

A 39% overall decline from 1966-2015 has been estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. Over 100 years ago, the Bewick’s Wren maintained stable populations in the Midwest, US and throughout many eastern and southeastern states but are now essentially extirpated from these regions, and exist primarily west of the Mississippi river. The declines are most severe in regions where House Wren (Troglodytes aedeon) populations have grown, namely Appalachia (Kennedy and White 1996). This appears to indicate competitive exclusion by the House Wren, a species that is known for being particularly aggressive toward the Bewick’s Wren, and even destroying their eggs and nests, (Kennedy and White 1996, Harrod and Green 2018). However, Habitat loss, pesticide use and interspecific competition with non-native synanthropic species, such as the European Starling (Sturnis vulgaris) and House Sparrow (Passer domesticus), are all thought to be contributing factors (Kennedy and White 1996).

Providing nest boxes where House Wrens are rare, or removing them where House Wrens are present is the extent of management at this point (Kennedy and White 2013). Although the efficacy of these practices has been sparsely documented, Harrod and Green (2018), in San Marcos, Texas, reported a negative correlation between shrub-land area to perimeter ratio and nest box success, suggesting that patch size and shape are important variables. Nests further from trees and in areas not exposed to large bands of edge habitat were more successful. The authors infer that this trend is probably related to edge effects and associated likelihood of predation. In another study, specifically investigating nest box usage by secondary cavity nesting species in Canadian County, Oklahoma, Jardine et al. 2016 observed that Bewick’s Wrens did not use nest available nest boxes at all. Tomasevic and Marzluff (2017) found that of the 18 Bewick’s Wren nests they observed, only 2 were in nest boxes. They also found that twice as many nest sites were in anthropogenic structures, including nest boxes, than in snags and other natural structures. More research on controls of nest success and limiting resources will be needed to best inform management practices in the future (Kennedy and White 2013).

The House Wren’s tendency to competitively exclude might run in the Troglodytidae family. Based on a recent study, it appears that the Bewick’s Wren may be competitively excluding a Troglodytid species. Farwell and Marzluff (2013) investigated whether there is evidence that urbanization of the Seattle area of Washington, US has facilitated or encouraged the aggressive exclusion of the Pacific Wren (Troglodytes pacificus) by the Bewick’s Wren, where human altered landscapes include patches of habitat suitable for both species. To address this question, the authors studied population and competition dynamics, and observed relative fitness and aggression between the two species at 27 study sites over a 12-year period, from 1998—2010. Results of the study provided evidence that ties anthropogenic landcover alterations to changes in abundance, abandonment of habitat by the Pacific Wren, and the occupation of such abandoned habitats by the Bewick’s Wren. The authors conclude that Bewick’s Wren colonization is likely to compound the issue of Pacific Wren habitat loss and recommend that conservationists allocate more attention to this additional pressure imposed on the sensitive native forest specialist.

Population trends from 1966-2015: Dot density represents the degree of population growth or decline. PAWR: Pacific Wren, BEWR: Bewick’s Wren, HOWR: House Wren. Data provided by North American Breeding Bird Survey.

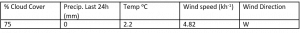

Observation #1

Date:

2/28/2019

Time:

1407

Location Information:

Mission Creek Park—East Olympia (Bigelow Highlands Neighborhood)

Coordinates: 47ᵒ 3.4499’ N, 122ᵒ 52.6094’’ W

Habitat: Early successional forest nestled within a large residential neighborhood—about 2 km east of downtown Olympia. Canopy is dominated by Alnus rubra and Acer macrophyllum. Understory is dominated by Vaccinium parvifolium, Rubus armeniacus, Oemleria cerasiformis, and Corylus cornuta. Forest floor is Gaultheria shallon, Polystichum munitum and Rubus ursinis. Contains a fair amount of down woody debris and brush. Adjacent to palustrine scrub/shrub wetland.

Weather:

Narrative:

A single individual Thryomanes bewickii foraging on a dead, lichen-covered shrub intertwined with Rubus armeniacus. Less than 3 seconds allocated to any given position on the shrub before hopping to the next spot. Completely non-vocal, and unresponsive to conspecific playback. Other species present in the area included Ixoreus naevius, Turdis migratorius and Junco hyemalis.

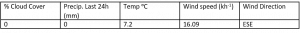

Observation #2

Date:

3/3/2019

Time:

0919

Location Information:

Mission Creek Park—East Olympia (Bigelow Highlands Neighborhood)

Coordinates: 47ᵒ 3.3886’ N, 122ᵒ 52.5636’’ W

Habitat: Early successional forest nestled within a large residential neighborhood—about 2 km east of downtown Olympia. Canopy is dominated by Alnus rubra and Acer macrophyllum. Understory is dominated by Vaccinium parvifolium, Rubus armeniacus, Oemleria cerasiformis, and Corylus cornuta. Forest floor is Gaultheria shallon, Polystichum munitum and Rubus ursinis. Contains a fair amount of down woody debris and brush. Adjacent to palustrine scrub/shrub wetland.

Photos taken at cardinal directions from observation location

Weather:

Narrative:

A male and female Thryomanes bewickii. The male was singing from the tip of a Corylus cornuta branch, while the female foraged in leaf litter. This went on for 15 minutes. The male alternated between two song types, one that ended with chu, chu, chu, chu, chu and the more recognizable Bewick’s wren song that ends with a trill.

Philip Hyde: B.S. with emphases in Ecology and Environmental Science, The Evergreen State College (Expected Graduation: Spring 2019)

Leave a Reply