Order: Passeriformes

Family: Paridae

Genus: Poecile

Species: Poecile atricapillus

Introduction

The Black-capped Chickadee is a small non-migratory song bird that is mostly found in deciduous and coniferous woods, as well as open woods and suburban areas. They are very widespread, and found coast to coast in North America, which includes much of Canada and the Northern two thirds of the United States. The top of their head is black all the way around and cuts off just under the eye. The cheeks are white with a black “bib” or chin and it has buff flanks (Sumlin. pers.obs.2012). Males and females are similar, though males are slightly longer and have a whiter plumage (Mennill 2003). There are several other North American species that are similar to the Black-capped Chickadee: Carolina Chickadees, Chestnut-backed Chickadees, Boreal Chickadees, and Mountain Chickadees (Stokes,1996). Black-capped Chickadee’s closest relative is the Mountain Chickadee ( Gill et al. 2005; Reudink et al. 2007), the main visible difference being a white eye stripe on the Mountain Chickadee. Though, the only ones found on the Evergreen campus are the Black-capped and the Chestnut-backed Chickadee (Sumlin. pers.obs.2012). Black-capped Chickadees can be distinguished from Chestnut-backed Chickadees by the absence of a chestnut colored nape (Sumlin. Pers.obs.2012). They also have slightly different sounding calls and songs from the Chestnut-backed Chickadees. Black-Capped Chickadees are well adapted to humans, and have even been known to feed from one’s hand!

As an observer it did not take me long to find a Black-capped Chickadee. There is quite a large population at (TESC) campus, especially around the bird feeders behind TESC library. They are also widely distributed among urban areas, I found many in my backyard (Elliot Ave. NW Olympia, WA 98502) (Sumlin pers.obs. 2012).

These birds prefer anywhere where they can find their two favorite foods: insect eggs and sunflower seeds. They like to perch in shrubs and moderately high in trees and are rarely found on the ground (Sumlin. pers.obs.2012). They are very active, quickly moving from place to place. Since Black-capped Chickadees do not migrate, they spend their winters in some very cold conditions in the Northern United States and central Canada. When small birds spend their winters in cold places, it requires prolonged expenditures of energy in thermogenesis (Cooper and Sonsthagen 2007). When regulating their temperature during the winter Black-capped Chickadees have the ability to self-regulate nocturnal hypothermia. Their temperature drops from about 108 degrees Fahrenheit to 88 Fahrenheit. By doing this, the Chickadee needs much less energy reserves to make it through a cold night (Cooper and Swanson 1994).

Recorded by Stephanie Lewis on October 21, 2012

Blackcappedchickadee 11/15/14 The Evergreen State College

Blackcap2 11/15/14 The Evergreen State College

BlackCap3 12/8/14 The Evergreen State College

Black-capped Chickadees are able to convey a lot of information about predators with their calls. The type of call and the length of call can tell conspecifics and, other nearby birds, about the predators in the area, what type of predator (raptors etc.) and if they are perched or flying . After the conspecifics are recruited, the Chickadees partake in a mobbing behavior towards the predator to ward it off (Templeton et al. 2005). The “chickadeedee” call can convey information about food and predators to other chickadees as well as other birds that travel with chickadees in mixed flocks(Wilson and Mennill 2011). In young birds, habitat quality has been known to effect song structure. One study observed that birds developing in mature forests had higher song consistency then birds in younger habitats. (Grava et al. 2013). Black Capped Chickadees are unusual among birds in that their calls are more complex then their songs (Ficken 1981).

When building nests, nest holes are excavated in rotted wood of mostly alder or birch trees. They also use bird houses and any other natural cavities. A pair usually raises one clutch a season (Lindsay 2011). A study was done on Black-capped Chickadee artificial nest preference using snags made out of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) tubes with and without wood shavings and wooden boxes with and without wood shavings. The investigators found the chickadees preferred to have wood shavings in their artificial nest sites and more often chose the PVC snags, most likely due to better protection than the wood boxes. This study concluded that PVC snags filled with wood shavings were the best artificial nest site for investigators to use while studying the breeding biology of chickadees (Cooper and Botner 2007).

In their movements, they are very “acrobatic” and agile through the air and as they hop on trees. This is a very useful when hiding from predators like American Kestrels, owls, squirrels, snakes raccoons, etc. (Sibley 2001). I’ve observed finding cover very quickly when they see or hear a raptor (Sumlin. pers.obs. 2012). In flight it brings its wings to its flanks and sort of falls through the air and then flaps and repeats it (Sumlin. pers.obs. 2012). In winter while they are in flocks they fly across streets or open areas one at a time with their bouncy flight (Sumlin. pers.obs. 2012) .

Because of their abundance, Black-capped Chickadees have been the subject of various studies, and much has been learned from them. However, there are still areas of the chickadees natural history that are unknown, and warrant future work. Juvenile dispersal and fall flock formation are two little known areas of study that could be expanded upon in the future. (Birds of North America Online).

11/13/14 10:15am Behind longhouse. Found 4 birds, 2 in view and 2 calling foraging low. lots of vertically scaling of the trees. Moss is a popular place to search for food. Joined a junco flock that was in the small trees in front of the longhouse. Moved to the trees around the feeders. most birds consumed seeds right away, one went a short distance and cached it. Flock started to disperse from the feeder, foraging in the trees around it.

11/14/14 2:38pm Red square/ Sem 1. 2 black caps calling in the teaching garden near the rotunda, flew to the sem 1 feeders. Joined by 2 other birds. flock taking sunflowers seeds and suet. One bird took a seed and placed it in several clumps of moss before finding the one it deemed acceptable.

11/15/14 10:14am behind library building. Chickadees in mixed flock visiting feeders behind the library. diverted from mixed flock and the flock leader was foraging around the clearing. Other birds are still in the trees near the feeders, calling often. Rejoined mixed flock as they headed toward driftwood road. Chickadees became single species flock as they reached driftwood. 4 birds fed in the alders on the side of the road before going deeper in to the wood towards the center of campus. A pair arrived on driftwood foraged for a bit then moved back into the woods towards the beach trail.

11/16/14 10:25am Behind library building. Flock of 5 birds visiting the feeders and foraging in the maples behind the library. They were communicating often as the flock got more spread out. The flock spent a lot of their time in the maples, with occasional trips to the feeders.

11/17/14 9:10 am Red Square. found solitary bird foraging in the trees at red square. bird was calling often until he joined a junco flock. Found a few birds behind the portables. foraging birds hammering, pecking and climbing vertically up trees. Lots of observations of birds when perched, leaning forward to search for food.

11/19/14 10:24am Sem II feeders. A pair of chickadees made 7 caching trips from the sem II feeders to the tall maple nearby. They would look for the thickest clumps of moss to store the seeds. This feeder offered un-shelled sunflower seeds, which may be easier to access later.

11/20/14 10:00am Nisqually NWR. Black-caps were part of a mixed flock foraging around the boardwalk. Similar foraging strategies to the evergreen birds. lots of vertical and horizontal hanging, pecking often. One bird fell behind the flock and preened in the thicket, stopping every now and again to fluff out its feathers. When a Peregrine Falcon flew over, the chickadees dove for cover. The low trees allowed me to observe the birds at eye level.

11/22/14 10:22am Lab I/ Sem II. Found a flock behind the lab building, moving through the small trees closest to the building. They are following a flock of juncos, preferring to following them instead of other birds due to their similar habitat. Perch and search behavior, bird is stationary and rotates its head around then flies to another branch. Re-found flock at Sem II feeders, the rest of the flock is on the other side of red square, calling to each other often. Some birds are caching in the maple trees, others in the “boxing glove” trees.

11/23/14 9:00am Lab I. Leading a mixed flock near the lab building. Started in the low bushes near the windows, then moved up to the ponderosa pine trees. Flock moved to Sem II feeders and i observed birds consuming seeds instead of consuming them. After finishing the seed the birds would wipe their bill on the branch they perched on. Most of the flock moved to the trees around the stairs next to the CAB. there were still a couple birds hanging around the feeder,joined by chestnut-backed chickadees.

11/24/14 9:15am Sem II. A few birds feeding in the trees and taking seeds from the feeder. Some birds caching, some eating them right away. A mixed flock arrived at the feeders. chestnut-backed Chickadees squabbled with the black caps at the feeder. A black cap chased a chestnut back off the feeder and into the brush both of them making similar chattering calls.

12/5/14 9:00am Sem II, light drizzle. A couple of chickadees were part of a good sized mixed flock at the Sem II feeders. The feeder is offering shelled sunflower seeds, some birds are making caching trips other are eating them right away. Every time they plan to cache a seed, they grab a seed from the feeder, fly to the top of the next tree over, then fly into the maple. Found another flock at the Sem I feeders. They grabbed some seeds them moved to the trees around red square, then circled around the rotunda.

12/6/14 9:45am Sem II. Found a lone bird in a mixed flock at the feeders. Was making caching trips. Was joined by a couple other birds feeding in the maple. Found more chickadees on the right side of the longhouse. one black cap was moving around in a small tree while another stayed perched giving soft calls back to the mobile bird. The moving bird started to preen, then caught up with his flock mates. the flock moved around to the back of the longhouse. The chestnut-backed chickadees crossed the road into the deeper conifer woods. the black-caps stayed in the deciduous trees, and circled around the longhouse.

12/7/14 9:30am, foggy, Red Square. Spread out flock moving through the trees on Red Square, calling often. 4 birds moved to the moss covered trees in the pollinator garden, searching the moss and giving it the occasional quick pecks. Flock seems particularly vocal, possible because of the thick fog. A couple birds perched and preening in front of the clock tower. Stated calling to the rest of the flock and flew to join them in front of Lab I. The flock moved to the Sem I feeders where the seed levels are also low.

12/8/14 9:30am,clear, Seminar. After quite a bit of searching, found a mixed flock with a couple black-caps. The flock moved to the front of the longhouse, and circled around the right side to the alder trees. The birds were too busy feeding to call much and their vocalizations were pretty spread out. They circled around the longhouse. 4 birds were in the same tree together, and a couple birds stopped to preen. The mixed flock started calling a lot, not sure what go them so worked up, possibly a predator in the area. After a couple minutes they calmed down. Moved to the trees around the Seminar building. the feeders are empty so the birds are mostly feeding in the trees. One bird made a brief trip to the suet feeder.

12/9/14 9:40am, rainy, Red Square. mixed flock in the trees in front of Lab 2. Black caps were at the back of the flock vocalizing often. The rest of the flock moved on and the Black caps stayed in a maple close to the rotunda. They were all over the maple inspecting and probing at the numerous mossy clumps.

12/10/14,10:08am, rain, Sem 2. Big flock of Chestnut-backed Chickadees and one black-cap. A couple more birds arrived at the feeder, and waited their turn to grab a seed. one ate right away, the other flew to the caching tree. Flock is pretty quiet, occasional chips here and there.

12/11/12, 9:30am, Sem 2. Large flock at the Sem 2 feeders. black-cap was chased off by a Chestnut back. Birds moved to the brush between the CAB and Sem 2, acrobatically foraging and probing on the small trees and branches. Reaching with their legs, hanging upside down and vertically perching.

12/12/14, 10:30am, Sem 2. Mixed flock between Lab 1 and the rotunda. Flock broke in half, some heading to the Sem 2 feeders others foraging in the pines near the rotunda. At the feeders black caps were grabbing seeds, some caching some eating right away.Chestnut-backed lunged at a black cap and scared it to the next branch over. bird grabbed a seeds flew it toward Sem 2 hammered at it then hopped from tree to tree, calling with the seed in its mouth. Something smacked against the window, causing the chickadees to dive for cover. they stayed in the brush calling to each other until a little time had passed and they resumed feeding.

Black-capped Chickadees rank among the IUCN’s (International Union for Conservation of Nature) conservation status as a least concern seeing as they are very common (All about birds, Black-capped Chickadee). Though, logging can be a potential threat to Black-capped Chickadees because for nesting they require soft rotting wood in which to excavate their nests. In northern British Colombia, nest success (number of young fledged) was compared between the habitats of an old-growth mixed forest or an undisturbed habitat and a forest that is regenerating due to logging or a disturbed habitat. The breeding densities in both habitats were similar but nests that were in the disturbed habitat fledged less successfully than the undisturbed habitat. Nest abandonment was the main cause of nest failure (Fort and Otter 2004). Recently, Black-capped Chickadees have become a victim of avian keratin disorder. This disease, in which rapid keratin production causes the bill to become deformed and over sized has a very high mortality rate. The exact cause of this disease is still unknown, though a viral or fungal infection is possible (Hemert et al. 2012)

![By Dreamdan (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://blogs.evergreen.edu/birds/files/2012/10/256px-Mesange_tete_noire.jpg)

By Dreamdan (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

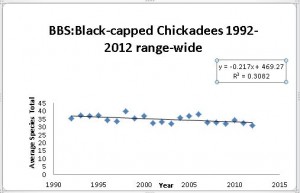

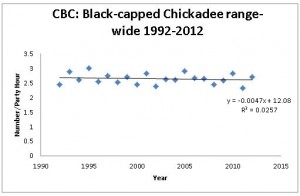

As displayed above, the range-wide population of this particular species of Chickadee are changing in some way. When looking at the range map below, you can see that the Black-capped Chickadee numbers in different locations have changed over time, but the overall population numbers have roughly stayed the same.

Breeding Bird Survey Distribution map of the Black-capped Chickadee from 1966-2012.http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/tr2011/tr07350.htm

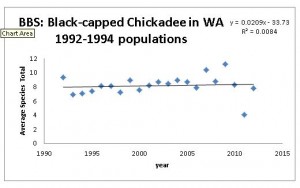

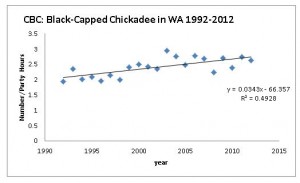

In the two figures to the right both sets of surveys, the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) and the Christmas Bird Count (CBC) show two slightly different sets of population changes for the Black-capped Chickadee in Washington State. The BBS data demonstrates that the populations of this species could just be moving around, and are not necessarily increasing or decreasing. The p-value for this data being 0.692 (p<.005 being significant). While the data collected during the CBC says that the population is increasing for Washington with a p-value of 0.0004.

What does this mean for the Chickadee? It means that their population numbers are stable, and maybe even increasing in the state of Washington.

Black-capped Chickadee. All About Birds. http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/black-capped_chickadee/id

Baker, T., Wilson, D., Mennil, D. 2012.Vocal signals predict attack during aggressive interactions in black-capped chickadees. Animal Behaviour. 84(4). 965-974. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347212003302

Brittingham,M., Temple, S. 1988. Impacts of Supplemental Feeding on Survival Rates of Black-Capped Chickadees. Ecology 69(3) 581-589. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1941007

Brotons, L., A. Desrochers, and Y. Turcotte. 2001. Food Hoarding Behaviour of Black-Capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) in Relation to Forest Edges. Okios. 95(3): 511 http://www.jstor.org/stable/3547507

Christie, P. J., Mennill, D. J., & Ratcliffe, L. M. (2004). Chickadee song structure is individually distinctive over long broadcast distances. Behaviour,141(1), 101-124.

Cooper, C. and D. Botner. 2007. Artificial nest site preferences of the Black-capped Chickadee. Journal of Field Ornithology. 79(2): 193-197. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27715259

Cooper, S. J. and D. L. Swanson. 1994. Seasonal acclimatization of thermoregulation in the Black-Capped Chickadee. The Condor. 96(3): Abstract. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1369467

Cooper, S. J. and S. Sonsthagen 2007. Heat production from foraging activity contributes to thermoregulation in Black-Capped Chickadees. The Condor. 109(2): 446-448 http://www.jstor.org/stable/4500975

Cooper, S. J. (2000). Seasonal energetics of mountain chickadees and juniper titmice. The Condor, 102(3), 635-644.

Desrochers, (1989) Sex, Dominance and Microhabitat use in Wintering Black-capped Chickadees: A Field Experiment. Ecology, 70(3), 636-645.http://www.jstor.org/stable/1940215

Desrochers,A., Hannon, S. Winter Survival and Territory Acquisition in a Northern Population of Black-Capped Chickadees. The Auk 105(4) 727-736.

Ficken, (1981) What Is the song of the Black-capped Chickadee?. The Condor, 83(4) 384-386. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1367513

Ficken, M.S., C. M. Weise, J. A. Reinartz. 1987. A complex vocalization of the Black-Capped Chickadee. II. repertoires, dominance and dialects. The Condor. 89(3):500-501 http://www.jstor.org/stable/1368640

Foote, Jennifer R., Daniel J. Mennill, Laurene M. Ratcliffe and Susan M. Smith. 2010. Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online:http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/039

Fort, K. T. and K. A. Otter. 2004. Effects of habitat disturbance on reproduction in Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile Atricapillus) in northern British Columbia. The Auk. 121(4): Abstract. http://dx.doi.org/10.1642/0004-8038(2004)121[1070:EOHDOR]2.0.CO;2

Gill, F. B., Slikas, B., & Sheldon, F. H. (2005). Phylogeny of titmice (Paridae): II. Species relationships based on sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome-b gene. The Auk, 122(1), 121-143.

Grava, T.,Fairhurst, G.,Avey, M.,Grava, A.,Bradley, J.,Avis, J.,Bortolotti, G.,Sturdy,C., Otter, K. Habitat Quality Affects Early Physiology and Subsequent Neuromotor Development of Juvenile Black-Capped Chickadees. PLoS ONE 8(8): e71852. http://www.plosone.org/article/citationList.action?articleURI=info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0071852

Kroodsma, D. E., B. E. Byers, S. L. Halkin, C. Hill, D. Minis, J. R. Bolsinger, J.A. Dawson, E. Donelan, J. Farrington, F. B. Gill, P. Houlihan, D. Innes, G. Keller, L.MacAulay, C. A. Marantz, J. Ortiz, P. K. S. Wilda and K. Wilda. 1999. Geographic Variation in Black-capped Chickadee songs and singing behavior. The Auk. 116(2): 388-390. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4089373

Lindsay, A. 2011. Black-capped Chickadee

(Poecile atricapilla). In A.T. Chartier, J.J.

Baldy, and J.M. Brenneman, editors. The

Second Michigan Breeding Bird Atlas.

Kalamazoo Nature Center. Kalamazoo,

Michigan, USA. http://commons.nmu.edu

Mennill D. J., S. M. Doucet, R. Montgomerie and L. M. Ratcliffe. 2003. Achromatic color variation in Black-Capped Chickadees, Poecile atricapilla: black and white signals of sex and rank. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 53(6): 350. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4602227

Otter,K., Murray, B., Holschuh,C., Fort, K. 2011.Rare insights into

intraspecific brood parasitism and apparent quasi–parasitism in black–capped chickadees. Animal biodiversity and Conservation. 34(1). 23-29. http://w110.bcn.cat/fitxers/icub/museuciencies/abc341pp2329.044.pdf

Otter, K., L. Ratcliffe, P. T. Boag. 1994. Extra paternity in the Black-Capped Chickadee. The Condor. 96(1). 218 http://www.jstor.org/stable/1369083

V. V. Pravosudov,, T. C. Roth II, M. L. Forister, L. D. LaDage, T. M. BurgM. J. Braun,B. S. Davidson. 2012. Population genetic structure and its implications for adaptive variation in memory and the hippocampus on a continental scale in food-caching black-capped chickadees. Molecular Ecology. 21(18). 4486-4497. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05721.x/abstract

Proppe, D.,Byers, K. Sturdy, C., St.Clair, C. 2013. Physical condition of Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) in relation to road disturbance. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 91: 842-845. http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/cjz-2013-0081#.VIIcTTHF_cF

Reudink, M. W., Mech, S. G., Mullen, S. P., & Curry, R. L. (2007). Structure and dynamics of the hybrid zone between Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) and Carolina Chickadee (P. carolinensis) in southeastern Pennsylvania. The Auk, 124(2), 463-478.

Schroeder, R. L. 1983. Habitat suitability index models: Black-capped Chickadee. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1 http://www.nwrc.usgs.gov/wdb/pub/hsi/hsi-037.pdf

Sibley, David. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. New York: Knopf, 2003. Print.

Sibley, D., J. Dunning, Jr., and C. Elphick. 2001. Chickadees. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior. 427-429

Smith, S. M. 1996. The single wing-flick display of the Black-capped Chickadee. The Condor. 98(4): 885 http://www.jstor.org/stable/1369879

Stokes, D. and L. Stokes 1996. Black-capped Chickadee, Boreal Chickadee, Chestnut-Backed Chickadee, Mountain Chickadee, and Mexican Chickadee. Stokes Field Guide to Birds. 1st ed.: 344-347

Sturman, W. A. 1968a. Description and analysis of breeding habitats of thechickadees, Parus atricapillus and f. rufescens. Ecology 49(3)

Sumlin, E. 2012. Ornithology, Fall 2012 Field Journal. Observations made from October 2012- November 2012. In Olympia, WA At Nisqually Wild Life Refuge, The Evergreen State College forest, and at my house (2407 Elliot Ave. NW Olympia, WA 98502). 27-30.

Sumlin, E. 2012. Ornithology, Fall 2012 Field Notebook. Obersvations made from October 2012- November 2012. At Nisqually Wildlife Refuge.12-15

Templeton, C. N., Greene, E., & Davis, K. (2005). Allometry of alarm calls: black-capped chickadees encode information about predator size. Science,308(5730), 1934-1937.

Tremblay, M. A. and C. C. St. Clair. 2011. Permeability of a heterogeneous urban landscape to the movements of forest songbirds. Journal of Applied Ecology. 48(3): 679-680 and 688

Turcotte, Y., & Desrochers, A. (2005). Landscape‐dependent distribution of northern forest birds in winter. Ecography, 28(2), 129-140.

Van Hermet, C.,Handel, C., O’hara, T. 2012. EVIDENCE OF ACCELERATED BEAK GROWTH ASSOCIATED WITH

AVIAN KERATIN DISORDER IN BLACK-CAPPED CHICKADEES

(POECILE ATRICAPILLUS). Journal of Wildlife Diseases.48(3). 686-694. http://www.jwildlifedis.org/doi/pdf/10.7589/0090-3558-48.3.686

Wilson, D.,Mennil D.(2011) Duty cycle, not signal structure, explains conspecific and heterospecific responses to the calls of Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus). Behavioral Ecology, 25(6),1-7