Order: Passeriformes

Family: Bombycillidae

Genus: Bombycilla

Species: Bombycilla cedrorum

The Cedar Waxwing is a medium-sized migratory passerine bird that ranges across North America. They eat primarily fruits, preferring high-sugar low-lipid fruits, in addition to airborne insects. They are known for their black eye mask, yellow bellies, “waxy” red-tipped secondary remiges, and yellow-tipped retrices.

Plumage

Males- The crown and neck of Cedar Waxwings are a light cinnamon brown color, fading into a sandier color on the back and wing coverts and a yellow belly. The remiges, lower back, rump, and retrices are a slate grey color, with red waxy tips on the end of the secondary remiges, and yellow-tipped retrices. The Cedar Waxwing wears a black mask lined with a thin white stripe. The mask extends from the forehead back to the edges of the crown where it fades, reaching narrowly above and more broadly below the eyes (Witmer et al. 2014).

Females- Adult females are similar in appearance to males, with duller plumage overall.

Immature Plumage

Juvenile plumage is distinguished from adult plumage by an overall grayer appearance, the belly is a whiter color with grey mottling. The crest feathers are much shorter, and the black mask may be less developed. Juveniles rarely have any waxy tips on secondaries, and the yellow tips of the retrices are narrower (Witmer et al. 2014).

Hatchlings are hatched naked, and young are altricial (Wetherbee and Wetherbee 1961).

“Waxy” Tips

The red waxy tips on the end of the secondary remiges are a flattened extensions of the feather’s shaft, colored red by the carotenoid astaxanthin, derived from the diet (Mountjoy and Robertson 1988). These tips mature later than the rest of the plumage, and are rarely seen on second-year birds. Cedar Waxwings are observed to mate assortatively based on the number of wax tips, suggesting they are a signal of status and age, and implies reproductive benefits the birds mating by age assortment (Mountjoy and Robertson 1988).

Yellow-tipped Retrices

The yellow tips of the retrices are normally colored by the xanthophyll carotenoids, derived from the diet. Orange-tipped variants have been observed in eastern North America, and it has been reported that this color variation is caused by the fruits of Morrow’s Honeysuckle. The invasive honeysuckle contains the carotenoid rhodoxanthin, which is not distinguished biochemically by the bird from xanthophylls, and when consumed during molting will turn the tips orange (Witmer 1996b).

Naked Parts

The iris has been observed to be reddish brown across age groups. Adults have black bills and feet, while juvenile bills and feet appear browner (Birds of North America). Hatchlings are hatched with a red mouth, bordered thinly by a yellow edge (Wetherbee and Wetherbee 1961).

Range

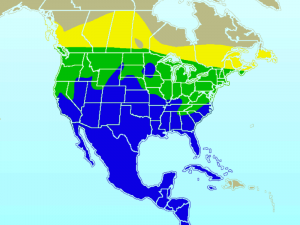

Yellow Indicates the breeding season (summer) range, Blue indicates the nonbreeding (winter) range, and green shows the year-round range. Range Map by Ken Thomas (www.kenthomas.us), found on commons.wikimedia.org

Cedar Waxwings winter in the southern United States and Mexico primarily, occasionally in southern Canadian provinces, and rarely occurring south of Central America.

Their breeding range extends as north as southeast Alaska, and as south and NW California across the United States.

They can be found year-round across the Northern United states and into southern Canada. (Witmer et al. 2014).

Migration

Cedar Waxwings breeding range in North America is from 35° to 50°N in the east and 40° to 55°N in the west (Brugger et al, 1994). Few overwinter in their breeding habitat, and most spend the winter in southern North America and Central America (Monroy-Ojeda et al. 2013) (Brugger et al 1994), with few sightings in northern South America (Witmer et al. 2014).

Cedar Waxwings rely heavily on fruiting shrubs and small trees to build habitat, as fruit makes up 84% of their annual diet (Witmer 1996a). Because of this, they gravitate towards open woodlands and shrubby fields as their main habitat, containing the plants that bear the high-sugar fruit they consume. They act as seed dispersers in their habitats (Ramírez and Ornelas 2009) (Longland and Dimitri 2016), maintaining a mutualistic relationship with the fruiting plants they feed on. (Witmer et al. 2014)

Cedar Waxwings eat mainly fresh fruits and insects (captured midair or gleaned from vegetation).

They are one of the most frugivorous birds of North America (Witmer 1996a). The winter diet consists almost exclusively of fruit, and the annual diet is 84% fruit, which is significant compared to the 54% fruit diet of the largely frugivorous American Robin (Turdus migratorius). Cedar Waxwings favor high-sugar and low-lipid fruit in their diet (Witmer 1996a). Historically, their winter diets have relied heavily on Cedar berries, but have since expanded to ornamental fruit trees and alien fruiting plants (Craves 2015).They also frequent agricultural fruit crops. Like Robins, they are frequent feeders in cultivated cherry orchards (Eaton et al. 2016). Biochemical studies have implicated alien shrubs, like the invasive Lonicera morrowii, in the orange color variation (from the usual yellow) on the tips of the retrices of Waxwings found in eastern North America. This is caused by a change in the carotenoid pigments derived from the diet (Witmer 1996b).

Come May, the Cedar Waxwings begin feeding primarily on aerial or vegetation-borne insects to fortify their diet in conjunction with the weathering of persistent fruiting plants for the remainder of spring. They are known for targeting hatching insects, like mayflies and stoneflies, over lakes and ponds. Their diet begins to increase in the consumption of fruit again during June through Sept (Witmer 1996a).

Deaths caused by the ingestion of toxic amounts of the cyanide-containing Nandia domestica have been documented in Georgia, USA (Woldemeskel 2010).

Cedar waxwings do not have a song, but make 2 distinct types of calls.

Bzee Call

The “Bzee call” can be described as “buzzy or trilled high-pitched notes made up of rapidly repeated elements” (Witmer et al. 2014). These calls have a “variable vibration frequency” and “marked vibrato” sound (Putnam 1949). Variation in the loudness, number of chirps, repetition rate, and duration of the call indicate the use of the call, ranging from “location (flocking) calls”, to male and female courtship calls and the “begging note” (hatchlings contacting the parent) (Putnam 1949).

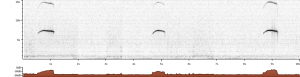

Examples of Bzee calls:

Mix of Bzee and See calls (Xeno-canto sonogram of recording by Jeff Dyck, British Columbia, June 2017).

See Call

The “See call” sounds like “high-pitched, hissy whistles that are tonal in quality” (Witmer et al. 2014). “See calls” correspond to the “Flock call” described by Putnam (Putnam 1949), and are largely associated with group flight during takeoffs or landing (Witmer et al. 2014).

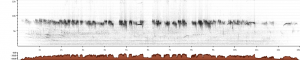

Example of See call:

See Call of Cedar Waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum) (Xeno-canto sonogram of recording by Frank Lambert, San Bernardino County, CA, May 2015).

Group see-calls

James Link, XC582126. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/582126.

Recording by James Link for Evergreen’s SURF project summer 2020.

Flight

Short flights are characterized by steady wing beats, and longer flights alternate between short wing beats and moments of gliding (Witmer et al. 2014).

Territoriality

They do not appear to be territorial throughout the year, except for males showing aggression surrounding the nest during the nesting season (Putnam 1949).

Mating and Pair Bonding

Mates appear to stay together for the second nesting of one season (Putnam 1949), but no information is reported of whether mates return to one another after a year. Cedar Waxwing mate assortatively based on the number of waxy tips on their secondary remiges (Mountjoy and Robertson 1988). Older birds, marked by more red tips, produce more young than younger birds (Mountjoy and Robertson 1988).

Cedar Waxwing’s engage in a “courtship hopping” routine, in which the male (usually) brings food toward the female by hopping sideways toward her on a perch. The food is passed to the female through a sideways head turn, and the female usually hops away from the male, then back towards it, and passes the food item back to the male. This passing back and forth happens several times, and the routine is complete once the female eats the food. This courtship display precedes copulation (Putnam 1949).

Sociality

Cedar Waxwings are a very social species, often traveling in flocks, especially in winter (Witmer 1996a).

For description of social calls, see: Vocalizations.

Predation

Cedar Waxwings are commonly preyed upon by Falcons and Hawks (Putnam 1949), specifically the Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii; Kennedy and Johnson 1986).

Cedar Waxwing populations have increased in recent years, possibly influenced by regeneration of shrublands and forests in the US. Cultivation of fruiting shrubs and trees for agriculture provide food and habitat to Cedar Waxwings (Witmer 1996b, Brugger et al. 1994). No conservation effort is currently needed, and some populations are even regarded as pests to agricultural crops (Witmer et al. 2014).

Causes of death to Cedar Waxwings range from pesticides, poisoning, and collision with man-made objects such as glass windows (Kummer et al. 2016) and TV towers (Witmer et al. 2014). They also have been documented as vulnerable to avian malaria (Granthon and Williams 2017).

Brugger, K., Lori N. Arkin, & Jean M. Gramlich. (1994). Migration Patterns of Cedar Waxwings in the Eastern United States (Patrones de Migración en Bombycilla cedrorum en el este de los Estados Unidos de América). Journal of Field Ornithology, 65(3), 381-387. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4513955

Craves, J. A. (2015). Birds that Eat Nonnative Buckthorn Fruit (Rhamnus catharticaandFrangula alnus, Rhamnaceae) in Eastern North America. Natural Areas Journal,35(2), 279-287. doi:10.3375/043.035.0208

Eaton, R. A., Lindell, C. A., Homan, H. J., Linz, G. M., & Maurer, B. A. (2016). American Robins (Turdus migratorius) and Cedar Waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum) vary in use of cultivated cherry orchards. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology,128(1), 97-107. doi:10.1676/wils-128-01-97-107.1

Granthon, C., & Williams, D. A. (2017). Avian Malaria, Body Condition, and Blood Parameters In Four Species of Songbirds. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology,129(3), 492-508. doi:10.1676/16-060.1

Kummer, J. A., Bayne, E. M., & Machtans, C. S. (2016). Use of citizen science to identify factors affecting bird–window collision risk at houses. The Condor,118(3), 624-639. doi:10.1650/condor-16-26.1

Kennedy, P. L. and D. R. Johnson. (1986). Prey-size selection in nesting male and female Cooper’s Hawks. Wilson Bulletin 98:110-115.

Longland, W. S., & Dimitri, L. A. (2016). Are Western Juniper Seeds Dispersed Through Diplochory? Northwest Science,90(2), 235-244. doi:10.3955/046.090.0213

Monroy-Ojeda, A., Grosselet, M., Ruiz, G., & Valle, E. D. (2013). Winter Site Fidelity and Winter Residency of Six Migratory Neotropical Species in Mexico. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology,125(1), 192-196. doi:10.1676/12-072.1

Mountjoy, D., & Robertson, R. (1988). Why Are Waxwings “Waxy”? Delayed Plumage Maturation in the Cedar Waxwing. The Auk, 105(1), 61-69. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4087327

Putnam, L. (1949). The Life History of the Cedar Waxwing. The Wilson Bulletin, 61(3), 141-182. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4157788

Ramírez, M. M., & Ornelas, J. F. (2009). Germination of Psittacanthus schiedeanus (mistletoe) seeds after passage through the gut of Cedar Waxwings and Grey Silky-flycatchers1. The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society,136(3), 322-331. doi:10.3159/09-ra-023.1

Wetherbee, D., & Nancy S. Wetherbee. (1961). Artificial Incubation of Eggs of Various Bird Species and Some Attributes of Neonates. Bird-Banding, 32(3), 141-159. doi:10.2307/4510881

Witmer, M. (1996a). Annual Diet of Cedar Waxwings Based on U.S. Biological Survey Records (1885-1950) Compared to Diet of American Robins: Contrasts in Dietary Patterns and Natural History. The Auk, 113(2), 414-430. doi:10.2307/4088908

Witmer, M. (1996b). Consequences of an Alien Shrub on the Plumage Coloration and Ecology of Cedar Waxwings. The Auk,113(4), 735-743. doi:10.2307/4088853

Witmer, M. C., D. J. Mountjoy, and L. Elliot (2014). Cedar Waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.309

Woldemeskel, M., & Styer, E. L. (2010). Feeding Behavior-Related Toxicity due to Nandina domestica in Cedar Waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum). Veterinary Medicine International, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://hindawi.com/journals/vmi/2010/818159/abs/.

Maya Nabipoor is a senior at The Evergreen State College, graduating in spring of 2019.

Page edited 8/22/2020 James Link. Sound file added.

Leave a Reply