Gavia immer -Marshfield, Vermont, USA – by Ano Lobb – Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons –

Order: Gaviiformes

Family: Gaviidae

Genus:Gavia

Species: Gavia immer

Introduction

The Common Loon (Gavia immer) also known as, Great Northern Loon, or Great Northern Diver, is an iconic, long-lived migratory waterbird, built for diving (Evers et al. 2010). (Hereafter referred to as “loons”).

Gavia immer -Marshfield, Vermont, USA – by Ano Lobb – Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons –

Loons are large, heavy-set waterbirds, with spear-like bills, and a low profile on the water (Piper et al. 2008). During the breeding season loons have a showy plumage displaying a black head, red eyes, and a white checkered pattern on their back, neck, and throat (Sibley 2003).

Non-Breeding Plumage Common Loon – by dfaulder – Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons –

During the winter, loons adopt a dull, gray-brown plumage and a partially white neckline and throat. During flight loons are streamlined and highlight their large feet and short tail (Paruk 2009; Sibley 2003).

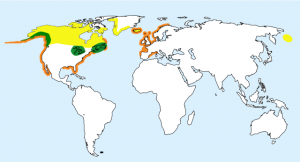

Yellow: Breeding

Orange: Non-Breeding

Green: Resident

Common Loon Distribution by Stongey-Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons –

Loons inhabit boreal and near-arctic salt and freshwater habitats across North America, breeding on lakes across the temperate United States north to Canada’s subarctic region (Kenow 2009). In Europe loons breed in Greenland, Iceland, and rarely Scotland (Evers. et al. 2010). Loons overwinter on coastline all across North America, and parts of Europe (Debark 2014; Kenow 2009).

Loons migrate during the day, starting long-distance migration in the morning (Kenow 2009). Loons depend on water for taking off, landing, and foraging (Gray et al 2014). Because of this they must fly long distances over terrestrial habitats during migration (Kerlinger 1982). Loons use large bodies of water such as stop-over sites during migration (Kenow 2009). Common Loon size effects migration distance regionally (Gray et al 2014). Larger loons benefit from close proximity of breeding and winter habitat, creating a pattern in which larger loons tend to live in close proximity to wintering grounds in comparison to smaller loons, which migrate longer distances, breeding further inland (Gray et al 2014). This phenomenon is due to the high levels of energy expended during migration (Gray et al. 2014). Loons fly at altitudes 973-2,167 meters above ground level. Over water loons fly 1-100 meters above the surface. Loons migrate at speeds of 74-98 mph depending on wind speed and direction during migration. Loons tend to migrate when tailwinds are favorable (Kerlinger 1982; Evers et al 2010).

Spring migration

Spring migration takes place between March and June, peaking in early May (Walter, H. et al. 1997). Loons will often congregate before beginning their migration to breeding lakes where they bond and form mating pairs. (Evers et al. 2010; Walter et al. 1997). The majority of loons breed in Canada, migrating from coastline across North America (Grear et al 2009).

Fall migration

Fall migration starts after the breeding season when juveniles become independent (Debiak. et al. 2014). Adults migrate separately from juveniles, which generally stay on breeding grounds until just before northern lakes freeze over (Debiak. et al. 2014). Loons migrate between September and October, with most migrants arriving at wintering grounds by late November (Evers et al. 2010). Western breeding populations migrate to the mid-Pacific coastline, Mid-continent loon populations migrate to the Atlantic coastline, and populations of the Upper Great Lakes migrate to the Gulf of Mexico (Evers et al 2010).

Loons occupy a variety of aquatic habitats. During the breeding season loons prefer habitats with clear water, an abundance of prey, and protected coves and islands for nesting. Protected rivers and reservoirs are also used if preferred habitat is not available (Spagnuolo, V. A. 2014; Evers. et al. 2010). Winter habitat is comprised mostly of protected coastline (Ford. et al. 1995). Occasionally loons will use rivers and reservoirs during winter and spring (Ford. et al. 1995).

Loons begin foraging shortly after sunrise, spending the majority of winter hours foraging (>50%). During breeding season time is split more evenly between foraging and breeding activities (Paruk J. D. 2008; Evers et al 2010; Shackleton, D. 2012). Loons forage by first ducking their heads under the water for a few seconds at a time (“peering”), to locate prey (McIntyre, J. W. 1978). Common Loons Feeding behavior includes subduing prey above water, as well as consuming prey underwater.

Common Loons feed primarily on fish, occasionally consuming crustaceans (Evers, et al. 2010). If breeding lakes are absent of fish, adults spend more time foraging and chicks are more dependent on parental care, relying heavily on leaches for food. Loons are largely solitary hunters, although during breeding season they will forage in pairs and on occasion congregate in loose foraging groups throughout the year (Hanson. and Kerekes. 2006). . Water clarity affects foraging success on breeding lakes because loons depend on sight to catch fish. Water clarity is not known to affect foraging success on wintering grounds, although loons do avoid highly turbid water (Thompson et al. 2006; Evers et al. 2010). Loons often dive for longer periods of time during ebb tide because they prey on benthic organisms which are disturbed by tidal currents (Thompson, S. A, and J. J. Price. 2006).

Walking

Loons spend the majority of their lives on water, only coming ashore during breeding activity. Loon’s feet are located far back on their body, making walking difficult, instead they use their feet, wings, and belly to scoot across terrestrial surfaces (Evers. et al 2010)

Swimming and Diving

Loons are built for diving with a streamlined body, large webbed feet, and air sacks to that can reduce and increase buoyancy. This enables loons to effortlessly float above water and sink underwater. Loons use their dexterous feet to propel and maneuver themselves once underwater (Evers et al. 2010).

Flight

Common Loon in flight Common Loon in flight Gavia immer -Marshfield, Vermont, USA – by Ano Lobb – Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons –

During local flight (non-migratory) loons fly low over the water at an average speed of 74 mph (Evers. et al. 2010). Loons need lakes with runways of at least 100 meters for takeoff and landing. Loons cannot take flight on land, during migration, loons that are blown off course and land in wet parking lots or fields become stranded (McIntyre, J. W. 1994).

Territoriality

During the winter Common Loons are mostly solitary, although they can be found in pairs, or small flocks (Judith W. McIntyre, 1978). In spring, loons are highly territorial over their breeding grounds. Intruders are subject to aggressive postures that emphasize the neck and breast and chasing, if these behaviors do not diffuse the territorial challenge, loons will resort to fighting, occasionally causing death due to spearing (Piper et al. 2008; Mager et al. 2007). Loons advertise territories with vocalizations. Males make a unique vocalization called a “yodel” to communicate size and individual physical condition, in response to intrusions into their territory (Mager et al. 2012). Common Loons will change their yodel when they move into a new territory, altering it to sound significantly different from the previous resident (Walcott et al. 2005).

Common Loons show aggression towards ducks, attacking ducks, and on occasion killing ducklings. This behavior decreases food competition, and has no consequences to the loons. (Sperry 2012).

Roosting

Non-breeding loons roost at night on open water and will congregate in groups a behavior known as “Night Rafting” this behavior reduces disturbance or the possibility of being washed ashore during a storm (Shackleton, D. 2012). Loons spend the majority of nocturnal hours sleeping; usually 92% of their night is spent sleeping, the remainder of the night is spent drifting and preening (Paruk, J. D. 2008; Piper. et al 1997).

Preening

Loons use their long bill to preen by first dipping it in the water, and wiping over uropygial gland (an oil gland in birds used for preening), before preening and bathing their body. Loons are one of very few species of birds that have a characteristic known as the “foot waggle.” The foot waggle is a behavior where loons stick their feet in the air while shaking them. Although the exact reason for the foot waggle is unknown, it is thought to aid thermoregulation, and is performed during preening as a comfort movement. Loons usually flap and expose their belly after preening (Paruk, J. D., 2009; Evers et al 2010).

Because loons have such a high wing load, and an inefficient wing form, take-off is a difficult process requiring a large runway of water. This adaption to flight requires loons molt all of their flight feathers at one time rendering them flightless. Because of this, non-breeding juveniles usually remain on saltwater where need for wings is less (Woolfenden. 1967).

Below is a description of the Common Loon molt.

First Pre-alternate Molt

Is an Incomplete, molt occurring between December and May on non-breeding. This molt includes some or all body feathers of the head and back, wing coverts, and the tail feathers. (Evers et al. 2010).

Second and Third Pre-basic Molts

Is a complete molt occurring during April through October, on non-breeding grounds. This molt includes Primary feathers, secondary feathers, and coverts replaced all at once. This molt is followed by a replacement of body feathers in July and October. This molt overlaps with an incomplete molt of head, back, breast, and tail feathers, called the second pre-alternate molt (Evers et al. 2010).

Definitive Pre-basic Molt

Is an incomplete to complete molt, primarily occurring between March and May as well as August through November. This molt occurs in two stages separated by a break during breeding. Wing feathers are replaced all at once during the March-May period on non-breeding grounds. During this period loons are flightless for 4-6 weeks. This is a cost effective way of molting because by removing buoyant feathers loons can dive more easily (Evers et al. 2010; Woolfenden. 1967).

Definitive Pre-alternate Molt

Is an incomplete molt, occurring between January and April. This molt occurs on non-breeding grounds. It includes almost all feathers of head, back, breast, flanks, and tail. This molt overlaps with the definitive pre-basic molt (Evers et al. 2010)

Loons breed on northern lakes, across North America, and parts of Europe (Evers et al 2010). Over 50% of breeding activity occurs in Canada (Grear et al. 2009). Loons are incredibly competitive over their breeding territories and will displace and take over territories (Paruk 1999).

Copulation and Monogamy

Loons are genetically monogamous (young are always genetic offspring of parents). The lack of extra-pair copulation in loons most likely developed as a by-product of joint territorial defense to prevent territorial takeover (Walter, H. et al. 1997).

Copulation occurs about once every other day during the pre-laying period. During breeding season, loons will display preceding copulation, with bill dipping, splashing, and diving. But because loons are monogamous, copulation is not necessarily preceded by courtship displays. Before copulation, the female loon seeks a suitable onshore or floating platform, before awaiting the male. Copulation is brief, with the male usually leaving the female within 20 seconds (Sverre Sjölander and Greta Ågren. 1972).

Nesting

“Loon nest” by Altaborn – Own work. Licensed under CC0 via Wikimedia Commons –

Loons nest on lakeshore, islands and floating sedge (Piper et al. 2001). Artificial and natural floating nest platforms increase nest success in common loons (Piper et al. 2001). These floating platforms are usually made up of sedge and other organic matter, creating a safe nesting site by decreasing nest predation, and flooding (McIntyre, and Mathisen 1997).

Eggs and Hatching

In the spring Common Loons form pairs and lay two to three eggs, although loons have been documented laying up to four eggs (Timmermans et al. 2012).. Loons lay their eggs over a period of 2-4 days (Piper et al. 1997). Over 50% of breeding activity occurs in Canada (Grear et al. 2009). After hatching, loon chicks bear an egg tooth on the tip of the upper mandible. This calcium tooth assists chicks breaking out of the egg. After hatching loons lose the egg tooth (Clark, A. G Jr. 1961).

Fledglings

Loon chicks are sub-precocial, meaning they leave the nest immediately but are still fed by their parents (Gill 2007). The fledgling stage lasts 2-3 months. Juveniles become independent as soon as they are able to fly and catch food. (Rodriguez 2002).

Predation

During the breeding season loon chicks, juveniles, and adults have a variety of predators, some of the common predators are: Bald Eagles, bears, coyotes, and pike (McCarthy et al. 2010). Adult Common Loons do not have any known predators during the non-breeding season (Paruk et al. 1998). Loons will mob mammalian predators and produce warning tremolo vocalizations if threatened (Barklow & Chamberlain 1984).

Loons produce iconic vocalizations of northern lakes, known for their eerie, far carrying sounds. Loons produce four different vocalizations: wails, yodels, tremolos, and hoots (Barklow et al. 1984). Physical encounters during territorial disputes occur often, and can result in fatalities. By communicating over long distances, loons minimize physical encounters with rivals. During breeding season loons vocalize at night because their vocalizations carry over longer distances compared to daytime vocalizations (Mennill, D. J. 2014). Loons rarely vocalize during winter (Evers et al. 2010).

Sounds

Soundscape (20 October 2012)

Taken at Geoduck Beach at 6:30pm. Weather: overcast, 50ºF, no wind.

Loonscape_10-20-2012

Tremelo by Robin Fletcher (10 October 2012) Taken at 7:30pm.

World population size for the common loon is estimated at 607,000 to 635,000 (Evers 2007), with at least 50% of breeding activity likely occurring in Canada. Population growth in some areas of the northern United States appears to have slowed during the past 2 decades. Explanations for changes in population growth include impacts from summer tourism land-use change acid mercury toxicity (Kenow et al. 2007), and lead poisoning from fishing tackle (Grear et al. 2009).

The Common Loon is currently listed as least concern on The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Evers et al. 2007). The majority of Loon populations are stable in the US, with exceptions being endangered populations at the state level. Loons are currently listed as Threatened in New Hampshire and Michigan (Evers et al. 2010). Loons are a species of Special Concern in Connecticut, Idaho, Massachusetts, Montana, New York, Washington, and Wisconsin (Evers et al. 2010).

Mercury and Lead

The Common Loon is sensitive to aquatic pollutants because it is a high-level trophic feeder (Evers. et al. 2010). High levels inorganic and organic pollutants pose a threat to the Common Loon, especially mercury. (Evers et al. 2010). Common Loons face exposure to high levels of Methylmercury (MeHg), aquatic mercury inputs caused by runoff and human disturbance (Evers. et al. 2003.). Lead poisoning from discarded fishing weights can cause death in loons, because they mistake them for stones, which they eat to aid with digestion (Franson et al. 2001)

pH and acidic breeding lakes

Low-pH in breeding lakes affects immune function and chick growth due to its correlation with reduced eggshell thickness, and MeHg (Evers et al. 2003; Pollentier et al. 2007). Low pH levels found in breeding lakes of the Common Loon are correlated with less suitable feeding and rearing grounds, caused by a change in prey ecology and foraging success rates. (Evers et al. 2003). Common Loons often choose to nest on lakes with low pH levels, because of their distance from human settlement (Evers et al. 2003). Acidic lakes also tend to have higher levels of MeHg.

Anthropogenic disturbance

Loons choose nest sites further away from human development if available (McCarthy, K. P., and Destefano. 2011). When presented with preferred habitat near to human settlements and less preferential habitat further from settlement, loons chose to nest on habitat farther from human settlement (Paruk, J. 2014). On lakes with high levels of activity, such as boat traffic, loons adapted to high levels of activity but still preferred nesting away from settlement, forgoing preferred habitat (Spilman et al. 2014). Habitat limitation could have a strong effect on territorial encounters between loons, causing more fatal encounters, as habitat shrinks due to human settlement and tourism (Grear et al. 2009).

Field Notes: On The Evergreen State College campus Common Loons can be found on Eld Inlet, along Geoduck Beach during most times of the day in fall and winter months (Campbell pers. obs.). They may be foraging close to shore, or preening in the middle of Eld inlet. A spotting scope or Binoculars will give you a good view if they are in the middle of the inlet.

Observations: All observations and analysis in this section was completed during November and December of 2014 by Lucas Campbell as a part of The Evergreen State College’s Ornithology program.

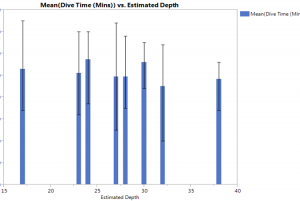

For my Analysis I used the null hypothesis that Depth does not affect dive time. I measured dive time during intervals of observation of 30 minutes to an hour. I estimated depth using NOAA depth charts of Eld Inlet. My analysis was not significant. With the sample size, I found no relationship between depth and dive time. I did regression analysis, plotting my data to test significance. My data showed a large spread and no significance: (Rsquare value of 0.03713) (F Ratio of 2.2751) (Prob > F of 0.1368). Bias in my study included, time constraints, a small sample size and limited access to research locations. To continue research on the study of depth on dive time, I would expand my observation locations and sample size. Due to my small sample size I was not able to come to a conclusion in my research.

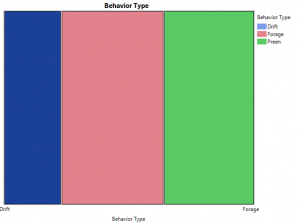

Percentage of Time Spent Drifting 23%

Percentage of Time Spent Foraging 41%

Percentage of Time Spent Preening 36%

I used JMP to create the Mean dive times with Depth on the x axis. I Included the range of all dive times (shown in lines)

Common Loon Behavior Data Sheet: Common Loon Data Sheet

11/7/2014

Evergreen Beach, Eld Inlet, Thurston County, WA.

47.084638-N, -122.978558-W

14:00-15:15

60°F, Clear skies and sun, Wind 10k/h

I spotted a Common Loon middle of the channel. Loon was foraging: diving, peering, and drifting. After a successful dive the loon caught 1 fish eating it above the water. Two loons were preening near each other at 14:15. Preening behavior of two loons included: wing flaps, foot waggles, and a majority of belly preening. At 15:15 the loons drifted around the sothern point of Evergreens beach and out of site.

11/8/2014

Evergreen Beach, Eld Inlet, Thurston County, WA.

47.084638-N, -122.978558-W

14:10-15:10

55°F, Clear skies and sun, Wind 5/h

I observed 2 loons preening: belly preening, back preening, wetting body and bill, flapping, and Repeating. One of the loons started forging, diving, and peering into water. The loon ate a fish above water the size of its bill at 14:31. The same loon ate another fish at 14:48; this fish was large double the size of its bill. The loon continued foraging until 15:08.

11/9/2014

Evergreen Beach, Eld Inlet, Thurston County, WA.

47.084638-N, -122.978558-W and 47.085321N, -122.976745-W

11:30-12:30

55°F, 60% cloud cover high winds, Wind 35k/h

No loons were found during this observation 11:30-12:15. There were large white-capped waves. A Gloucous-winged Gull was eating an apple, but stopped very quickly. I observed a horned grebe foraging, buffleheads and a cormorant on pilings near the northern point of Eld Inlet.

11/12/2014

Evergreen Beach, Eld Inlet, Thurston County, WA.

47.084638-N, -122.978558-W and 47.085321N, -122.976745-W

14:50-16:50

50°F, clear skies and high winds, Wind 25k/h

No were loons found during this observation. I spotted Surf Scoters, gulls, Horned Grebes, and Barrows Golden eyes. A Hooded Merganser pair was foraging in the middle of the channel. A Spotted Sandpiper was foraging in the shallows.

11/13/2014

Evergreen Beach, Eld Inlet, Thurston County, WA.

47.084638-N, -122.978558-W, 47.085321N, -122.976745-W and , 47.086523-N, -122.975179-W.

15:30-16:30

48°F, 100% cloud cover, Wind 15k/h

I observed two loons on the southern edge of Evergreen Beach they were drifting in separate directions; I observed preening and no noticeably successful dives. I observed three western grebes sleeping and preening. I four horned grebes observed diving and swimming.

11/14/2014

Evergreen Beach, Eld Inlet, Thurston County, WA.

47.084638-N, -122.978558-W and , 47.086523-N, -122.975179-W.

12:30-15:15

56°F, mixed sun and cloud cover, Wind 10k/h

I observed a loon found at 12:34 on the south side of Evergreens beach, it was north up the channel. The loon continued moving up channel foraging (diving and peering).the loon flapped its wings and dipped its bill after a successful dive. I lost the loon at 13:30. I later observed two loons peering + diving mixed with grooming. the loons continued diving near a moored boat mid channel at 14:10. Only one loon was left at 14:15, it was still foraging. the loon started preening at 14:30. The loon was swimming up channel 14:50 loon wetting bill after a successful dive. I lost the loon at 15:15.

11/15/2014

Evergreen Beach, Eld Inlet, Thurston County, WA.

47.084638-N, -122.978558-W and , 47.086523-N, -122.975179-W.

13:10-14:10

40°F, mixed sun and cloud cover, Wind 10k/h

I found a Loon preening and drifting between near shore and mid channel. The loon preened its belly, and back, flapping its wings and doing the foot waggle. The loon swam up the channel diving. Two large fish were caught. I lost the loon at 14:10

11/17/2014

Evergreen Beach, Eld Inlet, Thurston County, WA.

47.084638-N, -122.978558-W and , 47.086523-N, -122.975179-W.

12:30-13:30

40°F, mixed sun and cloud cover, Wind 10k/h

I observed a loon preening on the southern side of Evergreens beach. The loon started moving north up the channel, foraging. During this time it caught two fish. After 8 minutes of foraging the loon resumed drifting and preening behavior. Other birds I observed were: Varied Thrush, Red-Breasted Sapsuckers chasing, Double-Crested Cormorants, and a Western Grebe foraging.

11/20/2014

Nisqually Wildlife Refuge Address: 100 Brown Farm Road Northeast, DuPont, WA 98327. Area: 6.115 sq miles (15.84 km)

10:30-15:30

50°F, mixed sun and cloud cover, Wind 10k/h

I observed a loon for 30 minutes at Nisqually. During this time the loon caught 2 fish. Upon surfacing from a dive the loon emerged in between two buffleheads, who took flight. I believe this was an aggressive maneuver.

12/2/2014

Evergreen Beach, Eld Inlet, Thurston County, WA.

47.084638-N, -122.978558-W and 47.086523-N, -122.975179-W.

10:10-12:45

38°F, light rain, mist. Wind 5k/h

I observed two loons foraging and preening. One loon caught a very large fish. After surfacing the loon dropped the fish into the water, continuously biting it until it repositioned the fish enough to swallow it head first. Other behavior of note was sequential preening: preen back, belly, neck, flap and repeat.

Barklow, W. E., and J. A. Chamberlain. 1984. The use of the tremolo call during mobbing by the Common Loon. Journal of Field Ornithology 55:258-59.

Clark, A. G. Jr. 1961. Occurrence and timing of egg teeth in birds. The Wilson Bulletin 73:268-278

Debiak, A. L., McCormick, D. L., Kaplan, J. D., Tischler, K. B., & Lindsay, A. R. 2014. A molecular genetic assessment of sex ratios from pre-fledged juvenile and migrating adult Common Loons (Gavia immer). Waterbirds 37:6-15.

Evers, D. C., K. M. Taylors, A. Major, R. J. Taylor, R. H. Poppenga, and A. M. Scheuhammer. 2003. Common Loon eggs as indicators of Methylmercury availability in North America.” Ecotoxicology 12:69-81.

Evers, D. C. 2007. Status assessment and conservation plan for the common loon (Gavia immer) in North America. U.S. Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Technical Publication Washington, D.C., USA.

Evers, D. C., Paruk, J. D., Judith W. Mcintyre and Jack F. Barr. 2010. Common Loon (Gavia immer), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Franson, J. C., S. P. Hansen, Mark A. Pokras, and Rose Miconi. 2001. Size characteristics of stones ingested by Common Loons. The Condor 103:189-91.

Ford B. T. and Jennifer A. Gieg. 1995, Winter behavior of the Common Loon (Comportamiento Invernal de Gavia immer). Journal of Field Ornithology 66:22-29.

Gray, C. E., Paruk, J. D., DeSorbo, C. R., Savoy, L. J., Yates, D. E., Chickering, M. D., & Evers, D. C. 2014. Body mass in Common Loons (Gavia immer) strongly associated with migration distance. Waterbirds 37:64-75.

Woolfenden, G. E. 1967. Selection for a delayed simultaneous wing molt in Loons (Gaviidae). The Wilson Bulletin 79:416-420

Gill, F. B. 2007. Ornithology. W.H. Freeman and Company, NY, USA.

Grear, J. S., M. W. Meyer, J. H. Cooley, A. Kuhn, W. H. Piper, M. G. Mitro, H. S. Vogel, K. M. Taylor, K. P. Kenow, S. M. Craig, and D. E. Nacci. 2009. Population growth and demography of Common Loons in the northern United States. Journal of Wildlife Management 73:1108-115.

Hanson, A. R. and J. J. Kerekes. 2006. Feeding behavior and modeled energetic intake of common loon (Gavia immer) adults and chicks on small lakes with and without fish. Hydrobiologia 567:247-261.

Kenow, K. 2009. Migration patterns and wintering range of Common Loons breeding in the northeastern United States. Waterbirds 32:234-247.

Kerlinger, P. 1982. The migration of Common Loons through eastern New York. The Condor 84:97-100.

Mennill, D. J. 2014. Variation in the vocal behavior of Common Loons (Gavia immer) Insights from landscape-level recordings. Waterbirds 37:26-36.

McIntyre, J. W. 1978. Wintering behavior of common loons. The Auk 95:396-403.

McIntyre, J. W. 1994. Loons in freshwater lakes. In Aquatic Birds in the Trophic Web of Lakes. Springer Netherlands 280:393-413.

McIntyre, J.W., J.E. Mathisen. 1997. Artificial islands as nest sites for common loons Journal of Wildlife Management 41:317–319

Mager, J. N., C. Walcott, and W. H. Piper. 2007. Male Common Loons, (Gavia immer), communicate body mass and condition through dominant frequencies of territorial yodels. Animal Behavior 73:683-90.

McCarthy, M. P., Destafano S., and T. Laskowski. 2010. Bald Eagle predation on Common Loon egg. Journal of Raptor Research. 44:249-251.

McCarthy, K. P., and S. Destefano. 2011. Effects of spatial disturbance on Common Loon nest site selection and territory success. Journal of Wildlife Management 75:289-296.

Paruk, J. D., D. Seanfield, and T. Mack. 1998. Bald Eagle predation on Common Loon hick. The Wilson Bulletin. 111:115-16.

Paruk, J. D. 1999. Territorial takeover in Common Loons (Gavia Immer). The Wilson Bulletin 111:116-17.

Paruk, James D. 2008. Nocturnal behavior of the Common Loon, Gavia immer. Canadian Field-Naturalist 122:70-72.

Paruk, J. D. 2009. Function of the Common Loon Foot Waggle The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 121:392-398.

Paruk, J. 2014. Introduction: An Overview of Loon Research and Conservation in North America. Waterbirds 37:1-5.

Piper, W. H., D. C. Evers, M. W. Meyer, K. B. Tischler, J. D. Kaplan, and R. C. Fleischer. 1997. Genetic monogamy in the Common Loon (Gavia Immer). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 41:25-31.

Piper, W. H., M. W. Meyer, M. Klich, K. B. Tischler, and A. Dolsen. 2002. Floating platforms increase reproductive success of Common Loons. Biological Conservation 104:199-203.

Piper, W. H., C. Walcott, J. N. Mager, and F. J. Spilker. 2008. Fatal battles in Common Loons: A preliminary analysis. Animal Behavior 75:1109-115.

Pollentier, C. D., K. P. Kenow, and M. W. Meyer. 2007. Common Loon (Gavia immer) eggshell thickness and egg volume vary with acidity of nest lake in northern Wisconsin. Waterbirds. 30: 367-374.

Spilman, C. 2014. The effects of lakeshore development on Common Loon (Gavia immer) Productivity in the Adirondack Park, New York, USA. Waterbirds 37:94-101.

Shackleton, D. 2012. Night rafting behaviour in Great Northern Divers (Gavia immer) and its potential use in monitoring wintering numbers. Seabirds 25:39-46

Sibley, David. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. New York: Knopf, 2003. Print.

Sverre Sjölander and Greta Ågren. 1972. Reproductive behavior of the Common Loon. The Wilson Bulletin 84:296-308

Sperry, M. L. 1987. Common Loon attacks on waterfowl. Journal of Field Ornithology 58:201-05.

Spagnuolo, V. A. 2014. Landscape assessment of habitat and population recovery of Common Loons (Gavia immer) in Massachusetts, USA. Waterbirds 37:125-132.

Thompson A. S., and J. Jordan Price. 2006. Water Clarity and Diving Behavior in Wintering Common Loons Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology 29:169-175.

Timmermans, S. T. A., G. E. Craigie, and K. E. Jones. 2004. Common Loon pairs rear four-chick broods. The Wilson Bulletin 116:97-101.

Walcott, C., J. N. Mager, and W. Piper. 2006. Changing territories, changing tunes: Male Loons, Gavia Immer, change their vocalizations when they change territories. Animal Behavior 71:673-83.

Literature Reviewed and Cover Picture

Cover Picture: “Gavia immer -Wilson Lake, Minnesota, USA-8” by Pete Markham from Loretto, USA – More LoonsUploaded by Snowmanradio. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gavia_immer_-Wilson_Lake,_Minnesota,_USA-8.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Gavia_immer_-Wilson_Lake,_Minnesota,_USA-8.jpg

These Sources were reviewed and influenced the writing in minor ways. I am including them in the literature cited section under this header because they were not used as in-text citations.

Christmas Bird Count. Results and Analysis. Washington State, 1992-2012.

Common Loon Fact Sheet. 2012. NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation. New York State.

Common Loon. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. 2012.

Piper, W. H., K. B. Tischler, and A. Dolsen. 2001. Mother-son pair formation in Common Loons. The Wilson Bulletin. 113.4:438-41.

Pierre, J. P., S. M. Boss, and C. A. Paszkowski. 2005 Effects of forest harvesting on Bufflehead and Common Loon foraging behavior. Ornithological Science. 4(2): 161-168.

Leave a Reply