Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

Genus: Corvus

Species: Corvus corax

Introduction

By David Hofmann (Flickr) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Attributes:

By Peter Wallack (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

-very large for a Corvid

-adult length of up to 69 cm (27.17 in, 2.26 ft)

-adult plumage is entirely glossy black, juveniles tend to have some dark-brown

-relatively long, pointed wings

-wedge-shaped tail

-usually soars and glides during flight instead of flapping its wings rapidly

-elongated neck feathers (“hackles”)

-large, chisel-like bill

-Male and females are identical in appearance although sometimes varying in size

-Usually found in solitude or in single pairs

Distinguishing Characteristics From Crows:

-Ravens are much larger than crows

-Crows have a more fan-shaped tail

-The call of the Common Raven is much lower and hoarser that the call of a crow. Crow’s calls are higher-pitched and more nasally

-The feathers of Ravens tend to be pointed at the tip while the feathers of crows are rounded

-Ravens prefer wild areas while crows are more likely to occupy human-influenced areas

One of the most ecologically widespread birds in the world, Corvus corax is capable of occupying a large variety of places.

The U.S. and Canada: All over Canada, Alaska, and the Western U.S. including the entire coast and parts of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas. Much less found in Eastern U.S. states including parts of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, New York, Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. They have also been known to wander towards the Great Plains and the southern shores of the Great Lakes.

Mexico and Central America: Almost all of Mexico aside from the Gulf shores, all the way down as south as Nicaragua.

Europe, Asia, and Africa: Found in most of the Holarctic region from Northern Europe, Iceland, Greenland, Siberia, south to China, west to Africa, and back up through much of Europe.

Movement:

On the ground, the Common Raven normally walks by moving both feet and is rarely seen hopping in order to achieve distance. Its general flight behavior consists mostly of even wing-beats and periods of soaring. When targeting something on the ground, common ravens can be observed circling and slowing down their flight through rapid back-pedaling of the wings. On rarer occasions, individuals’ flights include dives and aerobatic rolls; in some cases as a mean for attracting a mate. On one occasion, an individual was observed flying upside-down for over a half mile!

Self Maintenance:

Corvus corax preens during all times of the year and their frequency of bathing is determined by the time since their last bath as well as other birds bathing. They bathe vigorously, even in freezing temperatures, and tend to do so in standing water. Common ravens also bathe in fresh snow and have been observed flying through sprinklers in order to clean themselves. They prefer to roost in protected places such as cliff faces, under rooves, and within conifer foliage but they are also known to choose telephone poles and wires, high buildings, and spots on the ground. At night, common ravens often roost in large numbers. They have been observed panting on hot days in order to cool off and sunning themselves as a way to obtain warmth. It is estimated that the Common Raven spends close to half of its time perching or resting on telephone poles, tree branches, towers, and the ground. Bonded pairs will often forage together but large, communal foraging groups are a common occurrence. They are most commonly seen feeding during the morning and afternoon but seasonal and weather changes within their environment can affect these patterns.

Sexual, Agnostic and Other Social Behavior:

Corvus corax is an extremely intelligent bird that is capable of displaying a wide array of complex social, sexual, and agnostic behaviors. Mating is generally monogamous and year-round with just a few observed exceptions of extra-pair copulations. The sexual display of the male can include appearing dominant, erect posture, fluffing heading feathers, bowing to the female, spreading tail feathers, gurgling/choking sounds, snapping of the bill, and aerodynamic feats during flight. Females will fluff out the feathers on their heads, flare their tails, spread their wings, and producing knocking calls. Bonded pairs are known to roost next to each other and display “affection” by grasping the bill or foot of their mate. Although the male does participate, the female does the majority of the collecting and placement of materials as well as the building of the nest into a woven basket. Their nests can reach up to five feet across and two feet high and are re-used by other mating pairs, if not the original builders, year after year. They have one brood of 3-7 eggs per year with an incubation period of 20-25 days. Upon hatching, the chicks are naked and sightless but they became

Non-monogamous, non-sexual pairing has also been observed in Common Ravens such as preening, feeding and play pairs or groups. When roosting in groups, they will congregate at a staging area before breaking in to smaller groups that fly to the roost at different intervals. Roosts serve the species as information centers and are generally open to strangers and new members.

Population Trends

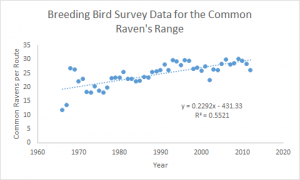

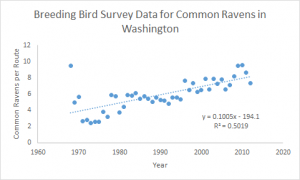

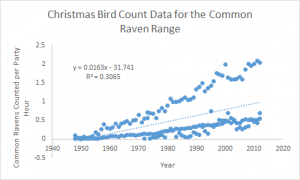

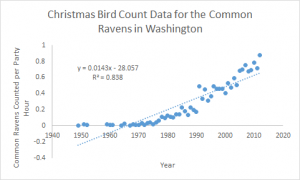

(All graphs produced by Kim Edgington for Winter 2014 “Avian Research and Monitoring Techniques”)

Both the Audubon’s Christmas Bird Count data and the United States Forest Service’s Breeding Bird Survey data both agree that the Common Raven’s population is expanding. In Washington State and across their entire range of Canada, United States, and Mexico the Common Raven is becoming more widespread. When these numbers were analyzed for variation using an ANOVA test in the statistical analysis program .JMP, p-values were significant with values at 0.0001. This proves that the increase of Common Ravens is not due to chance but their population is actually increasing at the rate shown in the graphs.

Conservation Issues

Common Ravens have the advantageous ability to thrive around human settlements such as campgrounds, landfills, highways, agricultural lands, and cities (Marzluff and Neatherlin 2006, Knight et al. 1995, Bodey et al. 2009, Boarman et al 2006). Scavengers are faced with a common problem, by feeding on remnants of large game left by hunters, they concentrate lead into their bodies from bullet fragments left in the tissue. However, this problem seems to be concentrated to local populations in areas with lots of hunting activity and is not affecting range wide populations (Craighead and Bedrosian 2008). The raven’s range wide populations are stable, even expanding into new areas previously not inhabited, such as the Mojave Desert and the Appalachian Mountains (National Geographic 2002, Knight et al. 1995, Boarman et al. 2006).

The Raven’s range expansion is creating numerous problems for conservationists, since corvids are known nest predators they present a large threat to sensitive species. The Marbled Murrlet (Branchyramphus marmoratus), which leave their nestlings unattended for several hours at a time while searching for food are suffering from heavy nest predation (Marzluff and Neatherlin 2006). In Great Britain, sensitive “upland” wader species like Lapwings (Vanellus sp.), and Curlews (Numenious sp.) are experiencing high events of nest predation by ravens due to the fact that their nesting sites are out in the open, on the ground (Amar et al. 2010). Researchers suggest to help these vulnerable species by returning habitat to it natural state, with limited edges. Forest edges create “edge effects” where corvids specialize both in feeding and nesting (Marzluff and Neatherlin 2006). Also removing individual ravens known to be common nest predators could help sensitive species recuperate their populations (Amar et al. 2010).

http://www.public-domain-image.com/full-image/fauna-animals-public-domain-images-pictures/reptiles-and-amphibians-public-domain-images-pictures/turtles-pictures/desert-tortoise/desert-tortoise-turtle-gopherus-agassizii.jpg.html

In the Mojave Desert, ravens are preying heavily on the Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii), listed as “vulnerable” by the IUCN Redlist (IUCN 2013). The juvenile tortoises have a soft shell for several years, problematic since some ravens have figured out how to easily pry the shells open. In this slow maturing species, long term damage is being done to the populations, younger tortoises are not surviving to sexual maturity and breeding in order to replace older generations as they die off (Boarman 2003, Boarman et al. 2006).

Human subsidization through food and water sources is one of the leading causes for the raven’s range expansion into new areas (Marzluff and Neatherlin 2006, Knight et al. 1995). Ravens can travel long distances form their territory to places to eat and drink (Janicke and Chakarov 2007), by utilizing human sources they have spread, feeding on garbage at landfills, roadkill on the highways, using agricultural irrigation for water sources, and using man-made structures as nesting sites in areas previously devoid of nesting habitat (Knight et al. 1995, Marzluff and Neatherlin 2006, Boarman 2003, Boarman et al 2006). Human activity is inadvertently supplementing larger, unsustainable populations of ravens. As with the Desert Tortoise, when the raven eats all of the tortoises, it will not starve like other species, it can fill its nutritional needs with a new or different food source. Conservationists recommend covering landfills and using scavenger proof garbage cans, removing carcasses from highways and cattle farms, and educating people on how to keep ravens from feeding on non-natural food sources to prevent further inadvertent population growth (Boarman et al. 2006, Boarman 2003, Marzluff and Neatherlin 2006, Knight et al. 1995, Janicke and Chakarov 2007, Amar et al. 2010).

Boarman, William I. and Bernd Heinrich. 1999. Common Raven (Corvus corax), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/476

Farrell, J. P. 1989. Natural history observations of raven behavior and predation on desert tortoises. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Land Manage. Needles, CA.

Mech, L. David. 1970. The wolf: the ecology and behavior of an endangered species. Univ. of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

http://www.shades-of-night.com/aviary/difs.html

Literature for Population Trends and Conservation Issues

National Geographic Society. 2002. National Geographic field guide to the birds of North America, Fifth Edition. National Geographic Society, Washington, DC.

Sibley, D. A. 2000. The Sibley guide to birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Sibley, D., Elphick, C., Dunning, J. B., & National Audubon Society. (2001). The Sibley guide to bird life & behavior. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Ehrlich, P. R., Dobkin, D. S., & Wheye, D. (1988). The birder’s handbook: A field guide to the natural history of North American birds : including all species that regularly breed north of Mexico. New York: Simon & Schuster

Mesopredators constrain a top predator: competitive release of ravens after culling crows

Bodey, Thomas W. ; Mcdonald, Robbie A. ; Bearhop, Stuart

Biology Letters, 2009, Vol.5(5), pp.617-620 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

Blood Lead Levels of Common Ravens with Access to Big-Game Offal

Craighead, Derek ; Bedrosian, Bryan

The Journal of Wildlife Management, 2008, Vol.72(1), pp.240-245 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

Spatial and temporal associations between recovering populations of common raven Corvus corax and British upland wader populations

Amar, Arjun ; Redpath, Steve ; Sim, Innes ; Buchanan, Graeme

Journal of Applied Ecology, 2010, Vol.47(2), pp.253-262 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

CORVID SURVEY TECHNIQUES AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CORVID RELATIVE ABUNDANCE AND NEST PREDATION

Luginbuhl, John M ; Marzluff, John M ; Bradley, Jeffrey E ; Raphael, Martin G ; Varland, Daniel E

Journal of Field Ornithology, 2001, Vol.72(4), p.556-572 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

Common ravens and number and type of linear rights-of-way

Knight, Richard L. ; Knight, Heather A.L. ; Camp, Richard J.

Biological Conservation, 1995, Vol.74(1), pp.65-67 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

Managing a Subsidized Predator Population: Reducing Common Raven Predation on Desert Tortoises

Boarman, William I.

Environmental Management, 2003, Vol.32(2), pp.205-217 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

Ecology of a population of subsidized predators: Common ravens in the central Mojave Desert, California

Boarman, W.I. ; Patten, M.A. ; Camp, R.J. ; Collis, S.J.

Journal of Arid Environments, 2006, Vol.67, pp.248-261 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

AsThe raven flies: using genetic data to infer the history of invasive common raven (Corvus corax) populations in the Mojave Desert

Fleischer, Robert C ; Boarman, William I ; Gonzalez, Elena G ; Godinez, Alvaro ; Omland, Kevin E ; Young, Sarah ; Helgen, Lauren ; Syed, Gracia ; Mcintosh, Carl E

Molecular ecology, 2008, Vol.17(1), pp.464-74 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

Gray Wolves as Climate Change Buffers in Yellowstone (Climate Change Buffers)

Wilmers, Christopher C ; Getz, Wayne M Dobson, Andy P. (Academic Editor)

PLoS Biology, 2005, Vol.3(4), p.e92 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

Effect of weather conditions on the communal roosting behaviour of common ravens Corvus corax with unlimited food resources

Janicke, Tim ; Chakarov, Nayden

Journal of Ethology, 2007, Vol.25(1), pp.71-78 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

Corvid response to human settlements and campgrounds: Causes, consequences, and challenges for conservation

Marzluff, John M. ; Neatherlin, Erik

Biological Conservation, 2006, Vol.130(2), pp.301-314 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

IUCN 2013. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. <http://www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 27 January 2014.

Leave a Reply