Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

Genus: Junco

Species: Junco hyemalis

Introduction

By Mike Baird [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

This page will detail the Oregon subspecies, which can be identified by its distinct black head, rufous flanks, chestnut back, and white to beige belly and breast. It also has white outer tail feathers that flash when in flight, a tan beak, and pink legs and feet. The Dark-eyed Junco is weakly sexually dimorphic. Males are slightly darker than females (Dunn 2002). Immature Juncos are somewhat browner and occasionally have streaked breasts. (Carroll 2004).

Distribution of all Junco hyemalis subspecies

By Ken Thomas [Public domain], via Wikimedia Common

At The Evergreen State College, Juncos are commonly found throughout brushy areas adjacent to buildings. They can be easily observed gleaning seeds below the bird feeders on the north-east side of the library building, and below the bird feeders on the south-west side of the Seminar I building. They are also common throughout The Evergreen Woods and along sidewalks, roadsides, and in the parking lots (Smith pers. obs.).

Some of the most frequent calls are the following:

Kew – which is usually repeated several times and can be heard throughout the year. It is usually heard during disputes and causes birds to move apart.

KewRecorded by Saff Smith, November 10th, 2012, in Olympia, WA

Recorded by Alice Dillon, December 2nd, 2014, in Olympia, WA

Twitter – a string of high notes, usually 6-19 syllables in length. It is produced by females pre-copulation, and by both sexes during aggressive displays. This sound tends to be heard more frequently in larger sized flocks (Smith pers. obs.).

TwitterRecorded by Saff Smith, November 10th, 2012, in Olympia, WA

Recorded by Alice Dillon, November 8th, 2014, in Olympia, WA

Tsip – a high frequency note, usually called 1-4 times in flight, and during flocking. On The Evergreen State College campus during non-breeding season this was the most often observed vocalization (Smith pers. obs.)

TsipRecorded by Saff Smith, November 10th, 2012, in Olympia, WA

(Sound descriptions after Balph 1977).

Males do not build nests or incubate their eggs (Whittaker et al. 2009). Clutch size is usually four eggs, with clutches of three or five common as well (Nolan et al. 2002). Dark-eyed Juncos are subject to brood parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbirds. About 50 percent of the time, the cowbird will remove Junco eggs from the nest (Whittaker et al. 2009). Young are born altricial (Sibley 2001), and remain in the nest for 11 to 12 days before fledging. Males and females tend to provide for their young equally during the nestling period (Reichard and Ketterson 2012).

Dark-eyed Junco’s reproductive habits change dramatically if their hormones are manipulated. In experiments where females have their testosterone levels elevated, they show increased aggression, and increase the amount of testosterone deposited in egg yolk. They decrease in body mass, immune function, choosiness over mates, and brood patch formation (Clotfelter et al. 2007). In males, experimentally elevated testosterone decreases parental care as well as survival of offspring, although usually results in higher overall individual fitness (O’Neal et al. 2008). This shows that hormonal regulation is a very important part of Dark-eyed Juncos’ reproductions cycles.

In recent studies, there is evidence to show that females use competitive traits to gain more access to resources which also has a positive affect on reproductive success. Aggression in females has positive and negative affects on the hatch lings. It was observed that aggressive females brooded less, but they fed the hatch lings more often. The aggression of the female does not have a direct affect on the mass of the egg (Cain et al. 2013).

Dark-eyed Juncos winter in small flocks in patchy wooded areas, and may forage with other sparrows and bluebirds. They have distinct social hierarchy that is based on several factors. Dominance is established by individuals that arrive earlier to winter flocks, and is also related to size. The dominance based on size may also be related to increased amount of white outer tail feathers. Females pick mates based on increased amounts of white tail feathers, thus allowing bigger birds to dominate sexually as well (Ferree 2007). Increased white plumage on the tail is related to increased age. Thus females show preference for older males. When females have been manipulated to have more tail white, males show neither preference or revulsion (Wolf et al. 2003). Juncos flash their white outer tail feathers to serve as an alert signal to their winter flock.

Dark-eyed Juncos undergo a full molt from the end of their breeding season to December (Bears et al. 2008).

Dark-eyed Juncos are mostly migratory, and follow food south, but will winter over if there is enough food. In studies, it was found that migratory Dark-eyed Juncos had better spacial memory than non-migratory Junco species, probably due to their more densely packed hippocampal neurons (Cristol et al. 2001). Males typically winter farther north than females, likely to be closer to the breeding grounds when females return to breed (Sibley 2001). Some Washington state birds are resident, but most migrate north to south or high in elevation to low in elevation. Non-migratory Juncos may have shorter wings than migratory birds. Their flight is very agile because they navigate tangled under-story. In flight, they flap continuously and pump their tails.

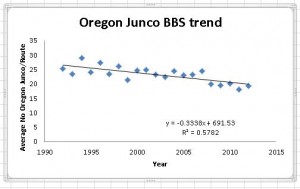

North American Breeding Bird Survey Data suggest that this species is in gradual decline in Washington State and Pacific Northwest rain forest. Some areas of the United States show population growth, mainly, along the Southern Appalachian mountains, Arizona, and parts of Wyoming (Breeding Bird Survey 2012).

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed the Dark-eyed Junco under the category of ‘Least Concern’ (BirdLife International 2012).

The Dark-eyed Juncos’ total population is estimated to be around 630 million (Nolan et al. 2002).

An illustration of a Dark-eyed Junco

http://www.johnmuirlaws.com/store/attachment/junco-dark-eyed-or-m-dark

Birds of Evergreen Terrestrial Species Spreadsheet – Alice Dillon

– 11/8/14 ~ 8:30am

Weather: Heavy cloud cover; No precipitation; No winds; 52°F

Roughly 8-12 individuals. Synchronized movements. Very vocal; alarm call when approached before quickly flying away together. While flying, white plumage on rectrices was extremely visible.

– 11/10/14 ~ 11:30am

Weather: Medium cloud cover; No precipitation; Light winds; 55°F

On TESC campus, SE side of Sem 1 building at the feeders. Watched five individuals perch on, near, and/or around the feeder. All individuals were low to the ground, usually no more than four feet. Only slightly vocal. Two individuals were on the ground, two individuals were perched on the feeder itself and one individual was perched in a nearby tree. The Juncos performed various forage attack maneuvers.

– 11/11/14 ~ 12:30pm

Weather: No cloud cover; No precipitation; Medium winds; 51°F

Same location as the day before. Watched one individual make multiple songs and calls, but said individual did not move much throughout his environment. He was standing on the ground and remained there for a period of 6-7 minutes.

– 11/14/14 ~ 1:45pm

Weather: Light cloud cover; No precipitation; Light winds; 53°F

Two males perched in the same tree on the N side of the library building on The Evergreen State College campus. These two individuals were perched the highest I had seen since I began my observations. One bird was perched roughly nine feet above ground and the other was perched roughly seven feet above the ground. They showed some mild examples of territorial behavior.

– 11/20/14 ~ 10:30am

Weather: Medium cloud cover; Little to no precipitation; Light winds; 49°F

At Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge, observed five individuals (four males and one female) forage for food along a small frozen stream. The female did not go onto the frozen substrate as much as the four other males did, but she remained close by. The birds seemed to be eating the thin layer of algae that rested on top of the frozen water’s surface. Most individuals would walk along the substrate and pick at the algae, then lift their heads up and do it again. An Anna’s Hummingbird (Calypte anna) flew over to a nearby tree branch during this time and the juncos became very vocal. The Dark-eyed Juncos seemed to be expressing some territorial behaviors although when the Anna’s Hummingbird came over, one of the male juncos quickly flew into a low bush beside the frozen body of water.

– 11/20/14 ~ 12:00pm

Weather: Medium cloud cover; No precipitation; Light winds; 51°F

Later in the day at Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge, I came across two individuals perched in a tree next to the walkway. They were perched at different heights within the same tree and constantly moved throughout it. I then noticed a third individual perched on the wooden walkway itself ahead of me about 15 feet. It stood there for a while and then flew out of my range of sight.

(Dillon pers. obs.)

Bears, H., Drever, M. C., and Martin, K. 2008. Comparative morphology of Dark-eyed Juncos Junco hyemalis breeding at two elevations: a common aviary experiment. J. Avian Biol. 39: 152 – 162.

Cain KE, Ketterson ED (2013) Costs and Benefits of Competitive Traits in Females: Aggression, Maternal Care and Reproductive Success. PLoS ONE 8(10): e77816. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077816

Clotfelter, E. D., Chandler, C. R., Nolan, V., Ketterson, E. D., 2007. The Influence of exogenous testosterone on the dynamics of nestling provisioning in dark-eyed juncos. Ethology 113, 18-25.

Cristol, D.A., Reynolds, E. B., Leclerc, J.E., Donner, A.H., Farabaugh, C.S., and Ziegenfus, C.W.S. 2001. Migratory dark-eyed juncos, Junco hyemalis, have better spatial memory and denser hippocampal neurons than nonmigratory conspecifics. Animal Behaviour, 66 pp 317 – 328.

Dunn, J. L. 2002. The identification of Pink-sided Juncos. Birding 34:432-442.

Ferree, E. D. 2006. White tail plumage and brood sex ratio in Dark-eyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis thurberi). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, Vol 62(1) pp 109 -117.

McGlothlin, Joel W., Neudorf, Diane L.H., Casto, Joseph M., Nolan, Val and Ketterson, Ellen D. Dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis): evidence for a hormonal constraint on sexual selection. (2004): 1377-1383.

Judd, S. D. 1901. The relation of sparrows to agriculture. U.S. Dep. Agric. Bull. no. 15.

National Audubon Society (2010). The Christmas Bird Count Historical Results [Online]. Available http://www.christmasbirdcount.org [12/1/12]

Newman, M.M., Yeh, P.J., and Price, T.D. 2006. Reduced territorial response in dark eyed juncos following population establishment in a climatically mild environment. (2006) Animal Behaviour 71, 893-899.

Newman, M. M., Yeh, P. J., and Price, T. D. 2006. Song Variation in a Recently Founded Population of the Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis). Ethology 114: 164 -173.

Nolan, Jr, V. E. D., Ketterson, D. A., Cristol, C. M., Rogers, E. D., Clotfelter, R. C., Titus, S. J., Schoech and E. Snajdr. 2002. Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://0-bna.birds.cornell.edu.cals.evergreen.edu/bna/species/716doi:10.2173/bna.716

O’neal, D.M., Reichard D.G., Pavilis, K., Ketterson, E.D. 2008. Experimentally-elevated testosterone, female parental care, and reproductive success in a songbird, the Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemails). Hormones and Behavior 54, 571 – 578.

Ramenofsky, M., Savard, R., and Greenwood, M.R.C. 1999. Seasonal and diel transitions in physiology and behavior in the migratory dark-eyed junco. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A 122 385 – 397.

Reichard, D. G. and Ketterson, E. D. 2012. Estimation of Female Home-range Size During the Nestling Period of Dark-eyed Juncos. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology Vol. 124 No. 3: 614 – 620.

Sauer, J. R., J. E. Hines, J. E. Fallon, K. L. Pardieck, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W. A. Link. 2011. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2010. Version 12.07.2011 USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD

Sibley, D. A. 2001. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior. 1st ed. Andrew Steward Publishing, New York, NY.

Sibley, D. A. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. 1st ed. Andrew Steward Publishing, New York, NY.

Smith, S. pers. obs. 2012. Field notes taken for an Ornithology class at The Evergreen State College, Ornithology Field Journal, 10/2/2012 – 12/10/2012, The Evergreen State College and surrounding areas within a one mile radius.

Sperry, J. H., George, T. L., and Zack. S. 2008. Ecological factors affecting response of dark eyed juncos to prescribed burning. The Wilson Journal of Orninthology 120 (1): 131-138.

T. V. Smulders, J. M. Casto, V. Nolan, Jr., E. D. Ketterson, and T. J. DeVoogd. Effects of Captivity and Testosterone on the. (2000): 24-252.

Whittaker, D. J., Reichard, D.G., Dapper, A. L., and Ketterson E. D. 2009. Behavioral responses of nesting female dark eyed juncos Junco hyemalis to hetero- and conspecific passerine preen oils. Journal of Avian Biology 40: 579-583.

Wolf, W. L., Casto, J. M., Nolan Jr. V., and Ketterson E. D. 2003. Female ornamentation and male mate choice in Dark-eyed Juncos. Animal Behaviour 67: 93 – 102

Additional Cited Sources

BirdLife International 2012. Junco hyemalis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. <www.iucnredlist.org>.

Burns, Christine M., Bergeon, Kimberly A. Rosvall, Thomas P. Hahn, Gregory E. Demas, and Ellen D. Ketterson. “Examining Sources of Variation in HPG Axis Function among Individuals and Populations of the Dark-eyed Junco.” Hormones and Behavior 65.2 (2013): 179-87.Science Direct. Web. 18 Nov. 2014.

Cain, K. E., C. M. Bergeon Burns, and E. D. Ketterson. “Testosterone Production, Sexually Dimorphic Morphology, and Digit Ratio in the Dark-eyed Junco.” Behavioral Ecology 24.2 (2013): 462-69. Oxford Journals.

Cardoso, Gonçalo C., and Jonathan W. Atwell. “On the Relation between Loudness and the Increased Song Frequency of Urban Birds.”Animal Behaviour 82.4 (2011): 831-36. Science Direct. Web. 18 Nov. 2014.

Cardoso, G. C., J. W. Atwell, E. D. Ketterson, and T. D. Price. “Song Types, Song Performance, and the Use of Repertoires in Dark-eyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis).” Behavioral Ecology 20.4 (2009): 901-07. Oxford Journals.

Carr, J. M., and S. L. Lima. “Heat-conserving Postures Hinder Escape: A Thermoregulation-predation Trade-off in Wintering Birds.”Behavioral Ecology 23.2 (2012): 434-41. Web. 19 Nov. 2014

Carroll, Aynsley. “Junco hyemalis (dark-eyed Junco).” Animal Diversity Web. Ed. Alaine Camfield and Kari Kirschbaum. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, 14 May 2004. Web. 8 Dec. 2014.

Dawson, William R., and John M. Olson. “Thermogenic Capacity and Enzymatic Activities in the Winter-acclimatized Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis).” Journal of Thermal Biology 28.6-7 (2003): 497-508.Science Direct. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Dillon, A. pers. obs. 2014. Field notes taken for an Ornithology class at The Evergreen State College, Ornithology Field Journal, 10/02/2014 – 12/11/2014, The Evergreen State College and surrounding areas within a one mile radius.

Gerlach, Nicole M., and Ellen D. Ketterson. “Experimental Elevation of Testosterone Lowers Fitness in Female Dark-eyed Juncos.” Hormones and Behavior 63.5 (2013): 782-90. Science Direct. Web. 17 Nov. 2014.

Holberton, Rebecca L., Ralph Hanano, and Kenneth P. Able. “Age-related Dominance in Male Dark-eyed Juncos: Effects of Plumage and Prior Residence.” Animal Behaviour 40.3 (1990): 573-79. Science Direct. Web. 17 Nov. 2014.

Holberton, Rebecca L., Timothy Boswell, and Meredith J. Hunter. “Circulating Prolactin and Corticosterone Concentrations during the Development of Migratory Condition in the Dark-eyed Junco, Junco Hyemalis.” General and Comparative Endocrinology 155.3 (2008): 641-49. Science Direct. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Pardieck, K.L., D.J. Ziolkowski Jr., M.-A.R. Hudson. 2014. North American Breeding Bird Survey Dataset 1966 – 2013, version 2013.0. U.S. Geological Survey, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center .

Peterson, Mark P., Danielle J. Whittaker, Shruthi Ambreth, Suhas Sureshchandra, Aaron Buechlein, Ram Podicheti, Jeong-Hyeon Choi, Zhao Lai, Keithanne Mockatis, John Colbourne, Haixu Tang, and Ellen D. Ketterson. “De Novo Transcriptome Sequencing in a Songbird, the Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis): Genomic Tools for an Ecological Model System.” BMC Genomics 13.1 (2012): 305. JSTOR. Web. 17 Nov. 2014.

Roth, Timothy C., and William E. Vetter. “The Effect of Feeder Hotspots on the Predictability and Home Range Use of a Small Bird in Winter.”Ethology 114.4 (2008): 398-404.

Satre, Danielle, Michael Reichert, and Cynthia Corbitt. “Effects of Vinclozolin, an Anti-androgen, on Affiliative Behavior in the Dark-eyed Junco, Junco Hyemalis.” Environmental Research 109.4 (2009): 400-04. Science Direct. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Swanson, David L. “Cold Tolerance and Thermogenic Capacity in Dark-eyed Juncos in Winter: Geographic Variation and Comparison with American Tree Sparrows.” Journal of Thermal Biology 18.4 (1993): 275-81. Science Direct. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Whittaker, D. J., K. M. Richmond, A. K. Miller, R. Kiley, C. Bergeon Burns, J. W. Atwell, and E. D. Ketterson. “Intraspecific Preen Oil Odor Preferences in Dark-eyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis).” Behavioral Ecology 22.6 (2011): 1256-263. Oxford Journals.

Wiley, R. Haven. “Prior-residence and Coat-tail Effects in Dominance Relationships of Male Dark-eyed Juncos, Junco Hyemalis.” Animal Behaviour 40.3 (1990): 587-96. Science Direct. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Leave a Reply