Order: Passeriformes

Family: Sturnidae

Genus: Sturnus

Species: Sturnus vulgaris

Introduction

The European Starling is a beautifully spotted, thrush sized bird that is common throughout most of North America. They are predominately black, with many star-like white spots with some browns and beautiful iridescence in their breeding plumages. Both sexes have the same appearance during non-breeding seasons, the males adopt an iridescent sheen to their heads and yellow bills when breeding (Birdweb). Sturnus vulgaris is a very smart and adaptable bird, who can exploit many different sources of food and nesting. Although they can survive just about anywhere, they prefer to live near humans. This is because their favorite method of foraging is for insects among short grasses, which is amply supplied by cut lawns and agricultural pastures. Human buildings also provide many nesting spaces, which also tend to be better heated than trees. European Starlings are social birds who prefer to forage, fly and roost with others of their own species (Sibley 2001). When breeding season rolls around, they tend to pair off, but stay within close proximity to other Starlings. European Starlings are an invasive species that was introduced from Europe. They have also been introduced to New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Jamaica and the West Indies.

By MPF [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

.

The European Starling prefers to be around human habitation. The main reasons for this are an abundance of discarded food and purposeful feeding (bird feeders) and an abundance of nesting areas within and around buildings, which also tend to be warmer than nests built in the wild. Sturnus vulgaris can be found throughout the eastern half of the United States, but in the West, they tend to avoid mountainous and forested areas, as well as arid places and deserts, in favor of staying closer to human habitations (Birds of North America Online). This is also true of the European Starlings found on the Evergreen campus, who tend to stay in the area around the Library, Red Square, dorms, fields, and academic buildings. They are scarce along the beach trails going through the Evergreen forest.

Sturnus vulgaris prefer to nest in cavities in trees, such as the ones that woodpeckers excavate for their nests. They also like openings and crevices in buildings. They are also known for stealing the nests of other birds and will even discard the eggs of others to get at them.

European Starlings are not picky eaters. They will primarily feed upon insects, berries, fruits and seeds. They will also exploit human garbage and livestock feed. Having this tolerance for a wide variety of food allows Sturnus vulgaris to be extremely adaptable and able to inhabit many diverse landscapes, which greatly increases its chances of survival. When very hungry the Starlings will eat from known food source locations. When satiated the Starlings will forage in locations where the food location isn’t known (Talling, Inglis, Van Driel, Young, and Giles, 2002).

Sturnus vulgaris have a wide range of calls and sounds that they can make. They are able to learn and develop their repertoire of songs and sounds throughout their life. The area of the brain that controls their ability to vocalize has been shown to be directly affected by the level of testosterone in the blood plasma (Absil, et al. 2003). This functioning allows the males to develop more and varied songs during breeding seasons to give him a competitive edge in the search for a mate. In fact, males will increase both their vocal repertoires and song lengths as they age; however they tend to plateau later in life, but will still vary up their repertoires (Eens 1992).

Social Behavior: European Starlings are social birds who can sometimes congregate into flocks of a million individuals (Birds of North America Online). The common flock size is much smaller than this and generally ranges in dozens of individuals. They tend to roost together, sometimes even occupying nests, boxes and cavities outside of breeding season, sometimes in pairs. Intensity of light and time of day influence not only how far they will range to roost but also their behavior along the way (Davis 1970). Despite this tendency to be social, Sturnus vulgaris can be susceptible to crowding stressors. In crowded conditions their heart rates and corticosterone levels increase and their behavior becomes more aggressive (Nephew, et al. 2005). The flocking of Sturnus vulgaris is also a defensive strategy against predators. During attacks by aerial hunters, such as Peregrine Falcons, they tend to make a wave pattern initiating from the location of the predator, that starts with a few birds and extends through the entire flock. This serves to increase their chances of avoiding the predator (Procaccini, et al. 2011).

Starlings preen themselves throughout the day and tend to like to bathe later in the day shortly before roosting for the night. Feather regrowth can be affected by poor physical health, such as during times of little food, and causes feathers to regrow smaller (Strochlic 2008). Sturnus vulgaris does suffer adverse affects due to psychological stress, this manifests as a rapid fluctuation in weight, first as weight loss during stress followed by over compensating weight gain (Awerman 2010). Another thing that causes stress in Sturnus vulgaris is being alone; it is shown that the stress related hormone, corticosterone, increases during isolation. This shows how social these birds really are (Apfelbeck 2008).

European Starlings do not tend to be highly territorial and often only defend their nests and the immediate vicinity in front of the nest during breeding seasons. Males will use calls and singing to establish mating territories but they do not defend feeding areas. However, male Starlings will fight each other over food and breeding sites by using their feet to clutch as they peck at each other. This can even continue until one dies, but rarely. Generally the loser will retreat. Sturnus vulgaris communicate with both voice and body movements and postures. They have very distinct threat and appeasement postures. When confronting another bird over food or mates, they will employ short rapid wing beats. They follow this up with a stare with heads raised, then escalating to fluffed up feathers and raising of the crown feathers, all to seem larger. The bird that submits will adopt a crouched posture with smoothed down feathers to appear smaller and non-threatening. European Starlings, like all birds communicate with calls and songs, but they can also mimic other birds very well. James Titus has observed them personally observed them imitating hawks and even bald eagles.

Mating: The process of mating for European Starlings begins with the males who search out suitable territories that include a cavity nest of some kind. Male European Starlings have been This is usually an old or stolen woodpecker nest, but can include the nests of other cavity nesting birds or even nooks and crevices in buildings, especially at the eaves. Sturnus vulgaris is an aggressive nest thief who will both chase away the resident birds and even dump their eggs from the nest. Once the selection of a nest is complete and a small breeding territory claimed, the name of the game is getting attention. To do this, the males sing, loud and often. When a female enters the area, they will accompany their songs with large circular wing beats to attract her attention. The presence of the female is usually enough to signal a rise in blood testosterone levels in the males (Pinxten, et al. 2003). An interesting thing about testosterone and aggressive behavior in male Starlings is that the two are not dependent upon each other. In non-breeding seasons, it has been shown that castrated males act even more aggressive than fertile males (Pinxten, et al. 2003). If the female finds the male acceptable, they will stay side by side throughout the copulation and egg-laying period. The male will stay close by as the female primarily spends her time feeding. This is to both insure that no interloping males impose upon his mate and to make sure that she doesn’t stray. Copulations outside of the pair bond are fairly frequent, especially when the male leaves the female alone, and are thought to be a type of insurance in case the female has paired herself with an infertile male. European Starlings are for the most part monogamous, but some polygyny happens. This generally occurs with a male having two female mates. Males don’t seem to have more than two mates, as the second female is generally neglected. She will have little help in feeding the offspring and this results in fewer fledged young (Birds of North America Online). This also leaves the two females more open to copulations with other males.

Sturnus vulgaris is an introduced species from Eurasia. This happened in 1890 and 1891, when hundreds of Starlings were introduced into Central Park in New York. The initial introductions failed, but more attempts were made until a breeding population was established. So successful were the Starlings, that by the 1950s, they had spread throughout the entire continental US and into Canada and northern Mexico. As both an invasive species and as a very successful species, there are no conservation efforts in place for Sturnus vulgaris.

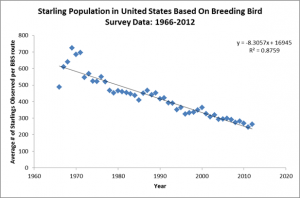

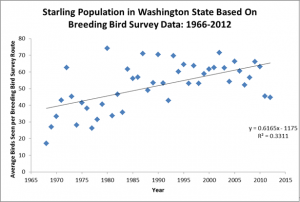

Bivariate fits of number of European Starlings seen per party hour by year were created for the period of time between 1966 and 2012 by Philip Bawn as part of avian research and monitoring methods coursework. These data were based on North American Breeding Bird Survey data from Washington state and countrywide. Washington state’s breeding bird survey data indicate an increase in starling observations over time (P<0.001). The nationwide breeding bird survey data are in concordance with the Christmas bird count data and show a possible decrease in national European Starling population (P<0.001).

Researchers are investigating population control of the European Starling and/or mitigating Sturnus vulgaris nesting. Providing nesting areas designed for native birds to use and deter European Starlings is one method that could be used successfully.

One attempt by researchers to test nesting deterrents involved the use of mirrors and flashing lights inside of nesting boxes during three consecutive breeding seasons. These tests involved covering the back and side walls of nesting boxes with mirrors, and putting flashing lights inside above the entrance to the boxes. During the year of installation, these treatment boxes were less likely to be used by starlings for nesting than control boxes without treatment. However, during the second and third year no repellent effects were noted. The treatments were found to deter native birds from nesting as well. Researchers concluded that further research involving mirrors alone is unwarranted but a combined approach should be investigated (Seamans, Lovell, Dolbeer, and Jonathon 2001).

Another way researchers attempted to test artificial nesting areas for starlings and native birds was through the creation of specially designed nesting tubes. 9.5-cm ID PVC tubes were built with capped ends and provided on utility poles in Ohio between 2009 and 2010. Researchers drilled 5.1-cm diameter entrance holes into one of the caps and then affixed the tubes to the poles at a height of 3 meters. For two years the Eastern Bluebird, House Wren, Tree Swallow, and to a much lesser extent the House Sparrow utilized the tubes for nesting. Most nests, (~90+%) were successful at fledging young. Starlings were able to enter this size of tube but did not use them for nesting. Significantly larger tubes (17-cm ID) were found to be used for starling nesting. Thus, small PVC tubes can meet the nesting requirements of native birds but are avoided by starlings (Tyson, Blackwell, and Seamans 2011).

Websites

BirdWeb: Seattle Audubon’s Guide to the Birds of Washington State. http://www.birdweb.org/birdweb/

The Birds of North America Online. http://0-bna.birds.cornell.edu.cals.evergreen.edu/bna/

Books

Gill, F. B. 2007. Ornithology Third Edition. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Proctor, N. S. & Lynch, P.J. 1993. Manual of Ornithology: Avian Structure & Function. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sibley, D. A. 2001. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior. New York: Alfred A. Knopf

Journal Articles

Absil, P., Pinxten, R., Balthazart, J., and M. Eens. 2003. Effect of age and testosterone on autumnal neurogenesis in male European starlings (Sturnus Vulgaris). Behavioural Brain Research 143:15-30.

Apfelbeck, B., and M. Raess 2008. Behavioural and hormonal effects of social isolation and neophobia in a gregarious bird species, the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris). Hormones and Behavior 54:435-441.

Awerman, J. L., and L. M. Romero. 2010. Chronic psychological stress alters body weight and blood chemistry in European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 156:136-142.

Davis, G. J., and J. F. Lussenhop. 1970. Roosting of starlings (Sturnus vulgaris): A function of light and time. Animal Behaviour 18:362-365.

Eens, M., Pinxten, R., and R. F. Verheyen. 1992. Song learning in captive European starlings, Sturnus vulgaris. Animal Behaviour 44:1131-1143.

Nephew, B. C., Aaron, R.S., and M. Romero. 2005. Effects of arginine vasotocin (AVT) on the behavioral, cardiovascular, and corticosterone responses of starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) to crowding. Hormones and Behavior 47:280-289.

Pinxten, R., de Ridder, E, and M. Eens. 2003. Female presence affects male behavior and testosterone levels in the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris). Hormones and Behavior 44:103-109.

Pinxten, R., de Ridder, E., De Cock, M., and M. Eens. 2003. Castration does not decrease nonreproductive aggression in yearling male European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Hormones and Behavior. 43:394-401.

Procaccini, A., Orlandi, A., Cavanga, A., Giardina, I., Zoratto, F., Santucci, D., et al. 2011. Propagating waves in starling, Sturnus vulgaris, flocks under predation. Animal Behaviour. 82:759-765.

Strochlic, D. E., and L. M. Romero. 2008. The effects of chronic psychological and physical stress on feather replacement in European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 149:68-79.

Seamans, T. W., Lovell, C. D., Dolbeer, R. A., and J. D. Cepek. 2001. Evaluation of Mirrors to Deter Nesting Starlings. Wildlife Society Bulletin 29:1061-1066.

Tyson, L.A., Blackwell, B.F., and T. W. Seamans 2011. Artificial Nest Cavity Used Successfully By Native Species and Avoided by European Starlings The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 123:827-830.

Talling, J.C., Inglis, I.R., Van Driel, K.S., Young, J., and S. Giles. 2002. Behaviour 139:1223-1235.

.

Philip Bawn is a student of The Evergreen State College studying for his dual BA/BS degree with emphases on health sciences and research. Philip is a pre-veterinary student and has hundreds of hours experience working with captive birds in veterinary and pet care settings.

Leave a Reply