Originally posted by: Caitlin McIntyre 2012

Edited and enhanced by: Riley Hendron 2014

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

Genus: Larus

Species: Larus glaucescens

Introduction

The Glaucous-winged gull is a large gull so named because of its uniquely colored gray wingtips, also recognizable by its characteristically pink feet. The overall size and wing color pattern make this species more distinguishable than other gulls. Juveniles of this species have distinct plumage correlating to their age that is often used in age identification Juvenile plumage appears mottled, gray, and their beak is a dark, worn looking, and black. Full-grown adult birds are distinguishable by a spot of red on the distal end of their yellow beak (Sibley 2003). Adults also sport a wingspan ranging from 47-56 inches, and have been shown to weigh up to 1.2 kilograms (Verbeek 1993). Sometimes identification can be tricky, as the species hybridizes with the Western Gull and the Herring Gull (Merilees 1974). Species identification in juvenile birds, particularly in gulls, can be extremely difficult.

In 1961, It was noted that not only was there diversity in plumage of Glaucous-Winged Gulls, but that the variety was being generated by the hybridization of the Glaucous-Winged Gull and the Herring Gull (Williamson 1963). Interestingly, the only notable difference between these two gulls and their hybrids were the color of their subterminal bands on their primary feathers; hybrids of these species landed somewhere in the middle: where Herring Gulls had black bands, the hybrids had grey but not glaucous colored bands(Williamson 1963).

By DickDaniels (http://carolinabirds.org/) (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

The Glaucous-winged Gull is common along the West coast of the North American continent (Hatch 2011). This species occurs from as far North as the Aleutian Islands in Alaska down to it’s Southernmost range of Baja, California. The Glaucous-winged Gull extends it’s range in the Winter and has expanded it’s territory to as far away as Japan (Henson 2004) and have even been found in an ocean adjacent county in England (Sanders 2010). In Washington, the bird is a year round resident and can be found near shores and beaches (Verbeek 1993). Because the Evergreen beach can be a great food source for these gulls, they can be found there at most daytime low-tides (Hendron pers. obs).

Migration in this species is known to be take up to 11 weeks when on their way south in the fall, but takes a mere 4 weeks when on the return in the spring(Hatch 2011); Though, not all Glaucous-winged Gulls migrate(Sibley 2002). Gulls found locally are not known to migrate and can be found year-round in Olympia.

The Glaucous-Winged Gull is a resident of the shore, and can be found near the water. This species is common in towns, at dumps and restaurant parking lots (McIntyre pers. obs.). These birds tend to live in relatively close proximity to their food source. These gulls have been known to nest both in small communities, and more isolated places (Vermeer 1988), and tend to nest on rocky cliffs along the coast or on islands and sometimes on flat tops of city buildings(Philips 2005). Individuals may cover various different types of habitats in a day in their effort to satisfy their nutritional needs (Phillips 2005).

Glaucous-winged Gulls are opportunistic omnivores and will take advantage of food scraps, when given the chance. They tend to feed on the ground or while floating on the water. The natural food source of this species, crabs, fish, sea stars, and a variety of mollusks can be found along the shoreline, in tidal pools and mudflats (Hendron Pers. Obs.). The diet of the Glaucous-winged Gull also includes human garbage, scraps, and discarded food items. They have also been known to prey on smaller passerines such as Song Sparrows and European Starlings; This behavior was noted on Mandarte Island of British Columbia(Nietlisbach 2014). They can also be seen picking off mussels that are stuck on the outer edges and undersides on docks and on wooden pilings (McIntyre pers. obs.). This species also has been known to steal food from crows, diving ducks and other gulls, this type of behavior is known as kleptoparasiticism (St. Clair 2001). This behavior was observed at Fry Cove Park on 3, November 2012: Two Glaucous-winged Gulls were using a dock to launch from in an effort to steal the morsels of food From three male Surf Scoters (Melanitta perspicallata). Once these three individuals did the work of diving and foraging for the mollusks, they returned to the surface only to have the thieving gulls greet them by swooping down in effort to scare them into dropping the prize (McIntyre pers. obs.).

These gulls can be seen ducking under the water next to a muscle covered dock , in order to resurface with a tasty treat. Interestingly, a Study conducted in the summers of 1975 and 77, suggested that Glaucous-winged Gulls do not perfect their fishing technique until their fourth year, in which they are considered fully matured (Searcy 1978).

Urban growth and its effect on the natural area has has its toll on the eating habits for these birds, though. A 2012 entry in the Marine Pollution Bulletin claims that 12.2% of the Glaucous-winged Gulls food was found to be made up of plastic. The article also notes that the most common type of plastic found to be in the bird’s diet was plastic film (Lindborg 2012).. These gulls are known for their opportunistic feeding habits, and while many prey on human produced resources, marine sources of sustenance were found to be a principal food source in most populations

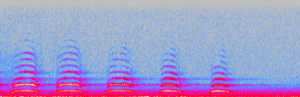

GWGU Above

sounds recorded by Caitlin McIntyre at Nisqually NWR, along boardwalk on mudflats on 10 Oct. 2012 between 2:30 and 2:40pm

sounds recorded by Caitlin McIntyre at Nisqually NWR, along boardwalk on mudflats on 10 Oct. 2012 between 2:30 and 2:40pm

Recorded at Percival Landing by Riley Hendron. The first clip on November 15th, the second on November 23rd.

Field Note Summary by Riley Hendron 2014:

Dates and Conditions:

11/5/2014: Geoduck Beach

- Sunny, about 35 degrees, 5MPH winds

- 1.5 hours observation

11/8/2014: Bayview Market

- Mostly sunny, 45-50 degrees, no wind

- 2 hours of observation

11/15/2014: Priest Point Park & Percival Landing

- Partly cloudy, about 40 degrees, mild wind (about 2 MPH)

- 3.5 hours of observation

11/16/2014: Percival Landing, Bayview Market, Capitol Lake, & Tumwater Historic Park

- Clear and sunny, about 40 degrees, mild wind (about 5 MPH), Frozen water in Capitol Lake.

- 2.5 hours of observation

11/20/2014: Nisqually Wildlife Refuge

- Cloudy, about 40 degrees, mild wind on boardwalk.

- 1 hour of observation

11/23/2014: Percival Landing

- Clear and sunny, about 35 degrees, no wind.

- 2 hours of observation

11/26/2014: Geoduck Beach

- Mostly cloudy, about 45 degrees, mild wind (about 8 MPH)

- 2 hours of observation

11/29/2014: Percival Landing

- Partly cloudy, intermittent light rain, about 45 degrees, mild wind (<5 MPH)

- 2.5 hours of observation

12/02/2014: Pecival Landing

- Sunny, about 38 degrees, no wind

- 2.5 hours of observation

Locally, natural habitat of the Glaucous-winged Gulls is the shore of the Pudget Sound. Finding them at the Evergreen beach and Priest Point Park is not hard as long as the tide is down. With the tide up, the best place to find these gulls is either near the docks in downtown Olympia, or in parking lots, particularly those that are sure to offer food scraps.

While observing these birds 5 behaviors seem to be critical in their routine: foraging for food, preening, loafing, swimming, and flying. In one hour down by the docks of Percival Landing all of these behaviors can be seen, with the birds switching intermittently between them. What poses the biggest question of what this bird considers to be time well spent, is its swimming and loafing behavior. On multiple occasions (11/15, 11/16, 11/23) this has been observed: a gull will stand on the dock, moving its head/ field of vision every 4-15 seconds, apparently looking for predators. This behavior will sometimes last up to 10 minutes before the bird will start preening or pursuing a new task. In the water, gulls can be seen displaying similar behavior; while letting the tide carry them in or out for about 90 seconds, and then swimming back to the spot in which they began, all the while looking around. With one individual, this behavior lasted for 12 minutes, without a clear purpose.

One particular observation period (11/15), at Percival Landing, 153 Glaucous-winged Gulls were counted on one dock, with 13 swimming around the dock.. This rose questions about their apparent lack of action. It was about 48 degrees, and sunny, with a light wind. One might guess that because these gulls have few predators by the docks, a comfortable amount of food, and at the time it was not breeding season, they are beginning to get accustom to not actively competing for resources. The same day, many gulls were observed jumping into the water from the dock, just to get a drink of water. It can be easy to mistake a gull gulping water for a gull tossing back a small snack (Hendron Obs 10).

The flocks noticed downtown have been the most populous, and the least mixed. In other places, like Priest Point Park as well as Nisqually (11/8 and 11/29, 11/20), they tend to forage by themselves, not far away from other species of bird and gull. One could speculate that with an increase in feeding grounds area, these gulls appreciate space from other birds. Though, during one session (11/23 Percival Landing), one crow approached a flock of Glaucous-Winged Gulls and began walking in the midst of a group of 23 gulls that were lounging on a dock at Percival Landing. This day was particularly cold (37 degrees Fahrenheit at midday, sunny), and the gulls were suspiciously quite. The crow in their midst, continued walking and occasionally making different calls that did not seem to be returned by any other crows. The gulls seemed to pay no attention to the crow, until it got a bit too close to a gull carrying food in its beak. The crow was then chased away (quietly) to a nearby fence where it eventually left. In addition, it is not uncommon to witness another species (not Glaucous-Winged) approach flocks of Glaucous-Winged Gulls, with no unusual interaction (seen on 11/15, 11/16, 11/23, 11/26, and 11/29). As far as the gulls seem to be concerned, unless another bird is encroaching on its food, they are welcome. During this specific observational period (11/23 Percival Landing), it took about 70 minutes of observation before hearing any calls or sounds from the gulls themselves. Usually gulls are much more vocal.

Another repeated behavior noticed at Percival landing was the harvest of muscles, which can be found on the side of most docks in the area. Gulls will get into the water, approach the dock, dip their head under the water, and after a few tries(usually no more than 5), come up with a muscle. Because the dock always had other birds on it, the gulls were no able to drop the muscles from on high without forfeiting the food to another member of the dock. Gulls would often take the muscle in its mouth, go to a secluded part of the dock (allowing there was one) and peck at the shell until it was opened. It is not uncommon to see other gulls approach those in the process of cracking open shells, in attempts to steal the catch from the deserving gull. In these cases, the defending gull would carry the unopened food in its mouth, while flapping its wings at the attacker (sometimes silently, sometimes with accompanying noise).

While Percival landing may be the easiest place to find these gulls, finding them at in smaller numbers at Geoduck Beach (11/ 5) and at Priest Point Park (11/15, 11/29) is also a possiblity. Finding gulls at low tide on the beach of both of these locations is relatively easy; it just takes some planning around the tide schedule. When the tide was at its lowest point in the day (About 3:30PM on 11/29 a total of 10 Glaucous-Winged Gulls were observed in the hour and a half I was on the beach. On the beach, much less loafing behavior was observed, as birds were trying to feed in these areas while they were able. This was a cold day in the 30’s and was sunny, soon to be cloudy. the gulls would wattle around the muddy/rocky beach in search of food, rarely going more than ten steps without pecking at something on the ground. Gulls seemed to walk around the beach for a short time (<10 minutes) and then fly to another part of the beach, sometimes 15 feet away, sometimes out of sight.

Glaucous-winged Gulls can often be seen cracking mollusks open (McIntyre pers. obs.). Birds carry them in their beaks as they fly up high and then drop them onto a hard surface. This behavior is displayed at the shoreline when the tide is low and the beach is exposed. During high tides that cover the entire beach, one can expect to see these gulls resting, preening and exhibiting general loafing behavior (McIntyre pers. obs.). Typically, mating takes place in Spring. Pairs tend to continue to mate monogamously until one dies (Hayward et al. 2008). The nest is a shallow dip, like a bowl and sometimes has a ring of vegetation or debris around the edge (Hayward et al. 2008). Nests tend to be on cliff ledges and sometimes on flat topped buildings. The average clutch size is about three eggs. Both parents incubate eggs for about a month. Newborn chicks are covered in down and sometimes leave nest just two days after hatching, although they stay close to the nest within sight of the parents. Both parents feed the young, which first begin to fly at 5-7 weeks old (Verbeek 1985). The red spot on the beak of the adults is thought to be used by the young as points where they can peck in order to get their parents to regurgitate some food (Verbeek 1985). Begging parents for food is a behavior that persists in juveniles and is easily notable by the distinguishing cries the young bird makes (McIntyre pers. obs.). The Glaucous-winged Gull takes four years to reach adult plumage (Reid 1987). This large gull usually lives to be ten years old but it’s been documented that individuals have lived to thirty (Campbell 2007). The oldest of this particular gull species was thirty seven and this bird was found in 2006 on Vancouver Island. This new longevity record made the Glaucous-winged Gull the 4th longest surviving species of birds in North America, contending with the two species of Albatross and the Great Frigatebird (Campbell 2007).

In 1951, a scientist argued that gulls should be a more prominent organism of study (Schultz 1951). She took on that challenge and in a subsequent publication, described acute behavior of the growth of young Glaucous-Winged Gulls, tracking growth and behavior from their egg stage (Schultz 1951). In this study, it was found that these gulls reach their peak weight and size at just as they reach full adulthood, from which point they plateau in both areas (Schultz 1951). This article described an adult gull as older than 45 months (Schultz 1951).

Additionally, it is thought that Glaucous-winged Gulls have the ability to learn through observation. In a study conducted in 2011, a group from Lomonosov Moscow State University, in Russia, researches trained gulls to perform tasks that they had not been observed doing outside of this study(Obosova 2011) The same authors took the study a step further in their paper published a year later in which they tested the birds abilities to discriminate between differing stimuli by quantifying their reactions to different shapes and colors. What they found was that the gulls tended to distinguish between colors and shapes, but not between the number (amount) of stimuli(Obozova 2012).

Gulls such as this are not known as common prey, but they do have predators. Eagles, and large mammals will pounce at the opportunity to catch a gull if they can (Hayward et. al. 2010). One journal also documented the predation of these gulls eggs by nearby river otters (Nicholaas 1978).

As far as Egg laying and molting goes, It has also been found that These gulls located on Mandarte Island near to Victoria B.C. schedule their primary molt just prior to their egg laying cycle, although the specifics of how many days prior has been shown to change from year to year (Verbeek 1979).

The Glaucous-winged Gull is not an endangered species by any means. The population size has risen over threefold in the past 50 years thanks to the accessibility of human produced scraps(Sullivan 2002). This species is protected by Federal Law, the Migratory Bird Act. In the case of the Glaucous-winged Gull,it is illegal to own one as a pet, but with the correct permits from the Fish and Wildlife Agency, they are fair game to hunt.. They are considered pests by commercial fisherman and dock workers because of the droppings they leave behind and their sometimes aggressive scavenging behavior (McIntyre Pers. Obs. 2012). The rate of population growth has slowed in the last ten years and in Washington state population has only increased slightly but the investment in egg production has decreased in the same time frame. Also, this species is commencing egg laying seven days later than they had historically (Blight 2011). Population in the Salish Sea has decreased by 25% between the late 1970s and early 2000s (Bower 2009). So while population raised significantly in the last century, more recent studies indicate a change and we have yet to identify and understand all the various influences that caused these changes. The next ten years will be a critical time to monitor population trends (McIntyre 2012. Pers. Obs.). Some studies suggest that the increase in numbers of Bald Eagles and their predation on breeding gull colonies may be a major contributing factor to the decline in abundance of Glaucous-winged Gulls in the Strait of Georgia (Hayward et. al. 2010).

There are efforts currently going on in our local community to both lethally and non-lethally rid an Olympia marina of gulls because the costs of cleaning gull droppings is expensive. Port of Olympia has a gull management contract with U.S. Department of Agriculture. They hired a contractor to go shoot gulls in Swantown marina with a pellet gun. Our local paper, The Olympian reports that since October of 2011, over 150 birds have been killed (Pawloski 2012).

There are also alternative to destroying these birds that may result in more harmonious interactions between the Glaucous-Winged Gulls and humans. The following are different ideas that could be used when implementing new methods of hazing or waste mitigation.

*Alter marina to make it not as attractive to gulls:

-place thick rubber mats over the concrete on the docks so that shells bounce off surface.

-scrape dock sides, remove mussels/food source from the dock

-add a floating bird dock with attractive hard concrete surface in shallow end of marina well away from boat traffic

-use ‘Bird B Gone’ spider fixtures (Marzluff’s suggestion)

*Change hazing methods:

-use green industrial laser to scare birds

-Hire falconer

-fly raptor shaped kites

-canine dock patrol

-focus efforts at high tide times

-throw out bag of feathers when shooting blanks, they form a negative association with the sound (Marzluff’s suggestion)

-capture, and band collect data on birds, they may avoid area afterwards, if not useful information could be collected

Andrew T. Baxter, John Allan. 2008. Use of Lethal Control to Reduce Habituation to Blank Rounds by Scavenging Birds. The Journal of Wildlife Management: Volume 72, Issue 7, pages 1653–1657

Aonghais Cook, Steven Rushton, John Allan and Andrew Baxter. 2008. An Evaluation of Techniques to Control Problem Bird Species on Landfill Sites. Earth and Environmental Science Volume 41, Number 6 (2008), 834-843

Belant, Jerrold L. 1997. Gulls in urban environments: landscape-level management to reduce conflict. Landscape and Urban Planning: Volume 38, Issues 3–4, 15 November 1997, Pages 245–258

Blight LK (2011) Egg Production in a Coastal Seabird, the Glaucous-Winged Gull (Larus glaucescens), Declines during the Last Century. PLoS ONE 6(7): e22027. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022027

Bower, J.L. 2009. Changes in marine bird abundance in the Salish Sea: 1975 to 2007. Marine Ornithology 37:9-17

Campbell, R. Wayne (2007) New Longevity Record of a Glaucous-winged Gull From British Columbia. Wildlife Afield: June Issue, Pages 78-80.

Cowles, David L., Galusha, Joseph G., and Hayward, James L. 2012. Negative Interspecies Interactions in a Glaucous-Winged Gull Colony on Protection Island, Washington. Northwestern Naturalist September 2012 : Vol. 93, Issue 2 pg(s) 89-100

Davis, Mikaela L. 2013. Dietary evology of the Glaucous-winged Gull (Larus Glaucescens) in the Pacific North-West: Conventional and Stable isotope techniques and implications for eco-toxicology monitoring. Simon Fraser University Thesis, Science: biological Sciences Department.

Ebels, Enno B, Adriaens, Peter & King, Jon R. 2001. Identification and ageing of Glaucous-winged Gull and hybrids. Dutch Birding 23: 247-270

Hand, Judith Latta, Southern, William E., Vermeer, Kees, 1987. Ecology and Behavior of Gulls . Studies in Avian Biology: Vol. 10

Hatch, Scott A., Gill, Verena A., and Mulcahy, Daniel M. 2011. Migration and Wintering Areas of Glaucous-Winged Gulls from South-Central Alaska. The Condor May 2011 : Vol. 113, Issue 2 pg(s) 340-351

Hayward, James L. and N. A. Verbeek. 2008. Glaucous-winged Gull (Larus glaucescens), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online

Hayward, James L., Galusha, Joseph G., and Henson, Shandelle M. 2010. Foraging-Related Activity of Bald Eagles at a Washington Seabird Colony and Seal Rookery. Journal of Raptor Research March 2010: Vol. 44, Issue 1, pg(s) 19-29

Henson, Shandelle M. et al 2004 Predicting dynamics of aggregate loafing behavior of Glaucous-winged Gulls ( Larus Glaucescens) at a Washington colony. The Auk April 2004 : Vol. 121, Issue 2 (Apr 2004), pg(s) 380-390

Henson, Shendelle M., Hayward, James L., J. M. Cushing, and Joseph C. Galusha. 2010. Socially Induced Synchronization of Every-Other-Day Egg Laying in a Seabird Colony. The Auk July 2010 : Vol. 127, Issue 3 pg(s) 571-580

Hipfner , J. Mark, Morrison, Kyle W. and Darvill, Rachel. 2011. Peregrine Falcons Enable Two Species of Colonial Seabirds to Breed Successfully by Excluding Other Aerial Predators. Waterbirds March 2011 : Vol. 34, Issue 1, pg(s) 82-88

Hipfner, J. Mark. 2012. Effects of Sea-surface Temperature on Egg Size and Clutch Size in the Glaucous-winged Gull. Waterbirds September 2012 : Vol. 35, Issue 3, pg(s) 430-436

Irons, David B., Anthony, Robert G. and Estes, James A. 1986. Foraging Strategies of Glaucous-Winged Gulls in a Rocky Intertidal Community. Ecology: Vol. 67, No. 6, pp. 1460-1474

Irons, David B., Steven J. Kendall, Erickson, Wallace P., McDonald, Lyman L., and Brian K. Lance. 2000. Nine years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill: effect on marine bird populations in Prince William Sound, Alaska. The Condor November 2000 : Vol. 102, Issue 4, pg(s) 723-737

Janssen, Jennider D., Mutch, William G. and Hayward, James L. 2011. Taphonomic effects of high temperature on avian eggshell. Palaios October 2011 : Vol. 26, Issue 10, pg(s) 658-664

Lindborg,Valarie A., Ledbetter, Julia F., and Walat, Jean M., 2012. Plastic Consumption and Diet of Glaucous-winged Gulls (Larus glaucescens).Marine Pollution Bulletin Vol. 64, issue 11, 2351-2356.

McIntyre, C. Personal observations, Ornithology Field Journal 10/1/2012 – 12/4/2012, Observations took place in South Puget Sound at The Evergreen State College shoreline at Eld Inlet and Swantown Marina at Budd Inlet, Olympia, WA. Pg. 6-50

Merilees, W. 1974. A Glaucous-winged Gull mated to a Herring Gull on Okanagan Lake, British Columbia. Canadian Field-Naturalist, 88: 485-486.

Murphy, E., R. Day, K. Oakley, A. Hoover. 1984. Dietary changes and poor reproductive performance in Glaucous-winged Gulls. Auk, 101: 532-541.

Nietlisbach, P., Germain, Ryan R., and Bousquet, Christophe A. H. (2014) Observations of Glaucous-winged Gulls Preying on Passerines at a Pacific Northwest Colony. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology: March 2014, Vol. 126, No. 1, pp. 155-158.

Nysewander, David R., Evenson , Joseph R., Murphie, Bryan L., and Cyra, Thomas A. 2001. Report of Marine Bird and Marine Mammal Component, Puget Sound Ambient Monitoring Program, for July 1992 to December 1999 Period. Wildlife Research and Management – Wildlife Research: January 26, 2001 Number of Pages: 194

Obozova, T.A., Smirnova, A.A., and Zorina, Z.A.Relational Learning in Glaucous-Winged Gulls (Larus Glaucescens) 2012. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, Vol. 15, issue 3, 873-880.

Obozova, T.A., Smirnova, A.A,. and Zorina, Z.A. 2011. Observational Learning in a Glaucous-winged Gull Natural Colony 2011. International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol 24, 226-234.

Pawloski, Jeremy, 2012. 150 gulls killed at Swantown. The Olympian: August 28th2012

Phillips, Karl W., Damania, Smruti P. Hayward, James L., Henson, Shandelle M. Logan, Clara J. 2005. Habitat patch occupancy dynamics of Glaucous-winged Gulls (Larus glaucescens) II: a continuous time-model. Natural Resource Modeling Volume 18, Number 4

Reid W. V. 1987. The cost of reproduction in the Glaucous-winged gull. Oecologia: Volume 74, Issue 3, pp 458-467

Reid, Walter V., 1988. Age-Specific Patterns of Reproduction in the Glaucous-Winged Gull: Increased Effort with Age. Ecology: Vol. 69, No. 5 pp. 1454-1465

Sanders, John 2010. Glaucous-Winged Gull in Gloucestershire: new to Britain. British Birds: 103, 53-59.

Searcy, William A 1978. Foraging Success in Three age Classes of Glaucous-Winged Gulls. The Auk, Vol. 95, No.3, 586-588

Sibley David A. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Glaucous-winged Gull: 193.

St. Clair, Colleen Cassady, St. Clair, Robert C. and Tony D. Williams. 2001. Does Kleptoparasitism by Glaucous-Winged Gulls Limit the Reproductive Success of Tufted Puffins? The Auk: Vol. 118, No. 4 pp. 934-943

Schultz, Zella M. 1951. Growth in the Glaucous-Winged Gull: Part I. The Murrelet, Vol. 32, No. 3( Sep. – Dec., 1951), pp. 35-42.

Sullivan, T. M., S. L. Hazlitt and M. J. F. Lemon. 2002. Population trends in nesting Glaucous-winged Gulls, Larus glaucescens, in the southern Strait of Georgia, British Columbia. Canadian Field-Naturalist 116: 603-606

Suraci, Justin P. and Dill, Lawrence M. 2011. Energy Intake, Kleptoparasitism Risk, and Prey Choice by Glaucous-Winged Gulls (Larus glaucescens) Foraging on Sea Stars. The Auk October 2011 : Vol. 128, Issue 4, pg(s) 643-650

Thiériot, Ericka, Pierre Molina, Jean-François Giroux. 2012. Rubber shots not as effective as selective culling in deterring gulls from landfill sites. Applied Animal Behaviour Science : Volume 142, Issue 1 , Pages 109-115 , 15 December 2012

Thomas P. Good. 2002. Breeding success in the Western Gull x Glaucous-winged Gull complex: the influence of habitat and nest-site characteristics. The Condor May 2002 : Vol. 104, Issue 2 (May 2002), pg(s) 353-365

Verbeek, N. 1986. Aspects of the breeding biology of an expanded population of Glaucous-winged Gulls in British Columbia. Journal of Field Ornithology, 57: 22-33.

Verbeek, Nicolaas A.M. and Morgan, Joan L. 1978. River Otter Predation On Glaucous-Winged Gulls on Mandarte Island, British Columbia. The Murrelet, Vol. 59, No. 3(winter, 1978), pp. 92-95.

Verbeek, Nicolaas A. M. 1979. Timing of Primary Molt and Egg-Laying in Glaucous-Winged Gulls. The Wilson Bulletin, Vol 91, No. 3 (Sep., 1979), pp 420-425.

Verbeek, N. A. M. 1993. Glaucous-winged Gull (Larus glaucescens). In The Birds of North America, No. 59 (A. Poole, and F. Gill, eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C

Vermeer K (1982) Comparison of the diet of the glaucous-winged gull on the east and west coasts of Vancouver Island. Murrelet 63: 80–85.

Vermeer K, Power D, and Smith J.G.E. 1988. Habitat Selection and Nesting Biology of Roof-Nesting Glaucous-Winged Gulls. Colonial Waterbirds, Vol. 11, No. 2 (1988), pp189-201.

Williamson, Francis S.L. and Peyton, Leonard J. 1963. Inbreeding of Glaucous-Winged Gull in the Cook Inlet Region Alaska. The Condor, Vol. 65, No. 1 (Jan.-Feb.,1963), pp. 24-28.

Zelenskaya, A. L. “Foraging Strategy of the Commander Islands Glaucous-winged Gull (Larus Glaucescens) Population.” Zoologičeskij žurnal 82.6 (2003): 694-707

Leave a Reply