Order: Passeriformes

Family: Regulidae

Genus: Regulus

Species: Regulus satrapa

Introduction

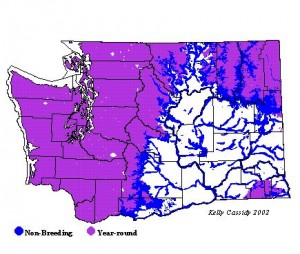

The Golden-crowned Kinglet is a mere 0.23 oz,, 8-11 cm songbird (Galati et al. 2012). The distinctive coloration helps in spotting this small bird in and around the Evergreen forest; olive grey or green coloration across dorsum, black moustacial stripe and white supercilium, , a golden crest lined in black two white bars on each wing, and black legs with yellow feet (Galati et al. 2012). These songbirds also can be identified by their tiny bill which is used for catching and eating various insects (Sibley 2003). Best distinguished from the Ruby-crowned Kinglet by the color of the crest (or lack thereof in female Ruby-crowned) and the black and white striping on the face of the Golden-crowned. The males also have a darker orange spot in the yellow crown that is more visible when the crest is erect (Sibley 2003).

Golden-crowned Kinglets are very active birds and can sometimes be hard to get a good look at in binoculars as they rarely hold still for very long. They can also be recognized by their call and behavior of foraging in the tops of coniferous and deciduous trees.

Common in conifers, these Passeriformes can be found usually pretty close to the tops of the trees. Many favor dense spruce and fir forests (Galati et al. 2012). These trees can usually be found at a higher elevation in the southern part of watershed. Spruce-fir stands makes up just 25% of the forest area within any given watershed (Biodiversity Assocs. V. US Forest Serv. 2002). This, arguably, proves to be advantageous to the kinglets and other species that make their home in these trees because they are more likely to be preserved during logging of an area. From a more recent study done in 2014, researchers Edmond J. Alonis and Gerald J. Niemi compared breeding bird communities of hemiboreal (halfway between temperate and subarctic) forest ecosystems in managed and unmanaged forests (Zlonis and Niemi 2014). Among the 35 species, Golden-crowned Kinglets were found most commonly in the unmanaged forest (Zlonis).

The Golden-crowned Kinglet can tolerate colder temperatures than the Ruby-crowned Kinglet, and are some of the smallest birds able to routinely endure freezing temperatures (as low as -40 degrees Fahrenheit) while maintaining a normal body temperature of approximately 110 degrees Fahrenheit (Lukes 2010). In fact, a study published in the Cooper Ornithological Society claimed that there is a small fluctuation of the daily lipid cycles in wintering Golden-crowned Kinglets that aid in keeping the birds warm during the winter. Contrastingly, birds with normothermic body temperatures have reserves that are inadequate for overnight energy demands (Blem and Pagel 1984). In a comparative study between of the metabolism of golden-crowned and ruby-crowned kinglets, researcher David L. Swanson found that the maximal cold-induced metabolism of the golden-crowned was significantly higher than that of the ruby-crowned. His conclusion was that “…metabolic differences may account for differences in cold tolerance” in these very similar Passerines (Swanson 2007).

Social behavior: sometimes seen in mixed flocks with Chickadees (National Audubon Society of Birds 2014). From my personal field observations, I have noticed golden-crowns in flocks ranging from two to eight mixed with chickadees, Pacific Wrens, and Brown Creepers. They interact with the other birds in the flock but tend to be attracted to other kinglets when picking who to forage near (again this is from my observations).

Breeding behavior: Kinglets are monogamous though they form new pairs every mating season (Galati 2012). Males tend to be territorial and establish a breeding area by making “tsee-tsee” vocalizations followed by an angry low pitched whinny and raising its crown. The female builds the nest, placed usually in dense spruce or firs, suing mosses, lichen, grass, conifer needles, paper strips and bark. Clutch size is 3 to 12, and incubation lasts for 14 to 17 days (Galati 2012).

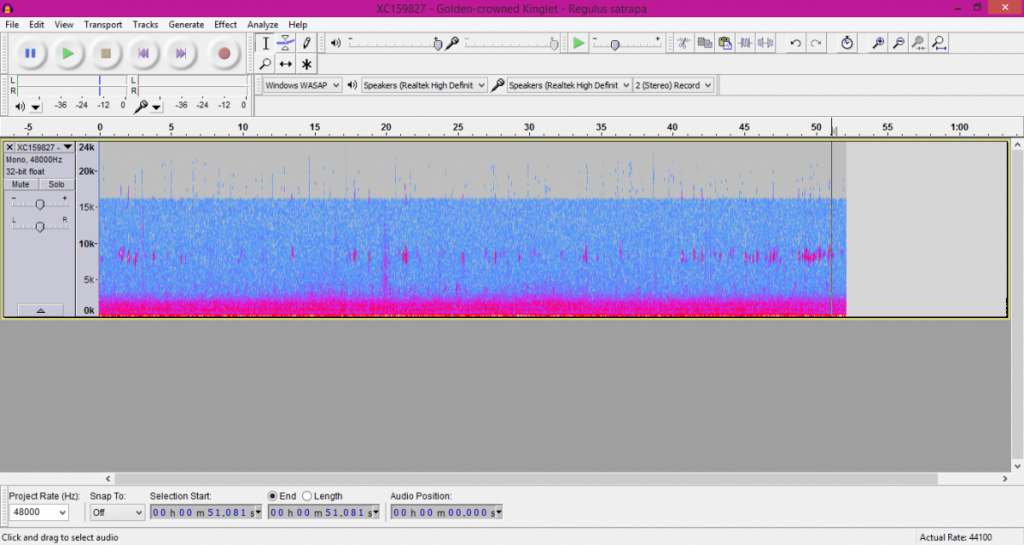

Recorder: Andrew Spencer

6.01.2014

British Columbia–kinglet song

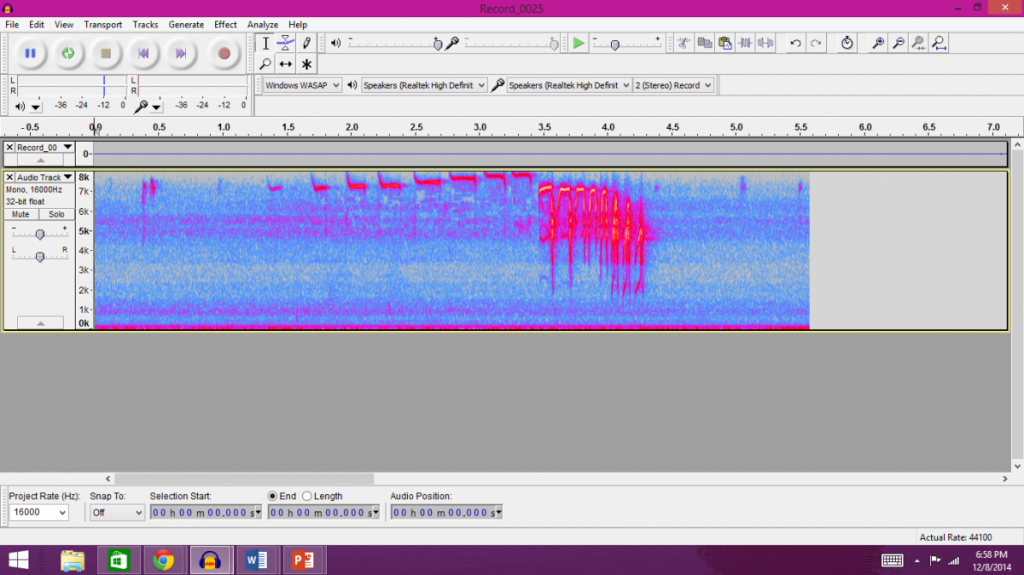

Recorder: Zoe Lovell

November 14, 2014 1:20 PM-2:20 PM

Location: Forest entrance behind soccer field on TESC– kinglet call

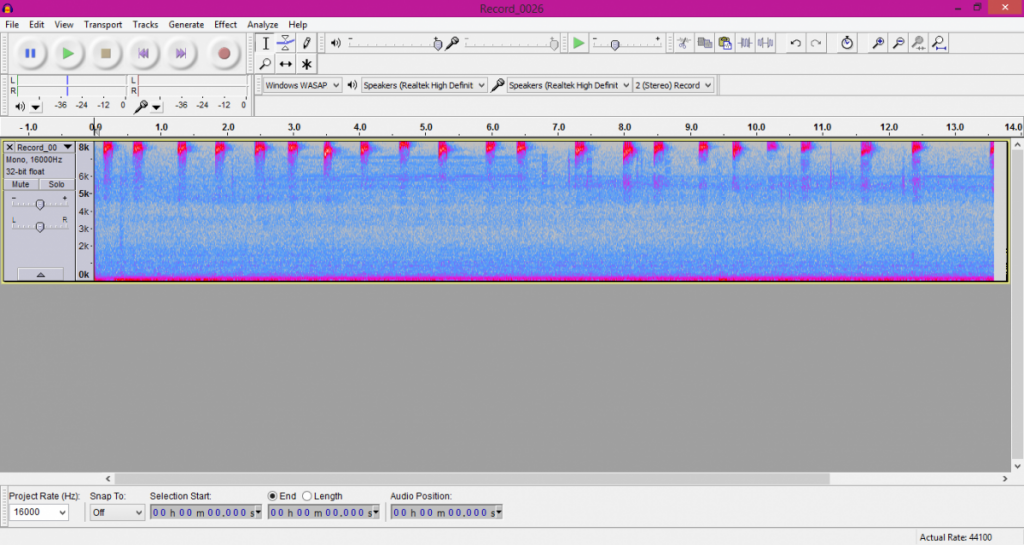

Recorder: Zoe Lovell

Dec. 6, 2014

Cooper’s Glen Apartments, Olympia, WA–kinglet call while foraging

Golden-crowned Kinglets have a distinct high pitched “tzee-zee-zee” sound as well as different, more elaborate vocalizations; sometimes compared to the sound of twinkling bells. From looking at the structure of its sonogram, the Golden-crowned Kinglet can easily be mistaken for the Firecrest of Europe (Naugler 1993). On campus, Brown Creepers can often be mistaken for them because of their similar calls.

A group of Ornithologists recently found that detectability has a narrow range for Golden-crowned Kinglets because of its relatively high frequency and tendency to reside high in the canopy, sometimes even 75 m (Rempel et al. 2013).

Here, you can find journal entries from my personal accounts observing these birds…

Birds-of-Evergreen-Terrestrial-Species-Spreadsheet

November 12, 2014 2:27 to 4:27 PM

Location: Outskirts of coniferous forest behind library of TESC campus, 47.0730° N, 122.9762° W

Weather: Clear skies, low temp of ~38 degrees F

I was attracted to the forests’ edge by the distinctive “tzee-zee-zee” sound of the kinglets. It took me a moment to actually see them because they were so high above me and so tiny. But against the still sky I could see their movements and shadows behind leaves of what I believe to be an Alder Tree. Even without binoculars, I could see the bright yellow crests on each bird. They foraged together on each tree for an average of 8 minutes in a group of about 4. From this distance of about 12m, all the birds look to be about the same size and I believe this to be a single-species flock. Before finding this community of tiny birds, I was struggling locating kinglets from the inside of the forest because the cover of the canopy made it difficult to locate the source of the many kinglet calls I heard. Therefore, my advice to any birders on campus looking for the Golden-crowned Kinglet is to search near the edges of forested areas and really familiarize yourself with the calls and songs this bird makes.

November 14, 2014 1:20 PM-2:20 PM

Location: Forest entrance behind soccer field on TESC, 47.0730° N, 122.9762° W

Weather: clear skies with temp of 42 degrees F

I can hear this lone Kinglet making long “zeeee-zeeee” sounds as I walk along the path next to large coniferous trees. When I whistle my best imitation, it calls back to me. It doesnt sound like an alarm call, more like a call to other kinglets or perhaps other birds from a mixed flock. Walking closer, I think I have found the tree to focus my binoculars on. Sure enough I see the grey rump of a tiny kinglet on the spindly branches of a maple tree. As it called, I was able to get a relatively good recording that can be heard in the Sound section of the blog. After about 15 minutes of the bird calling and listening, I heard more birds from the canopy above. The kinglet’s “tzee-zee” and the pacific wren’s “kit kit” were sounds I identified. The longer i watched, the more I heard; mind you, these were not songs but instead foraging vocalizations. The kinglet I had originally been watching held onto the branches and flicked its wings twice before taking off to the canopy above beyond my view.

November 19, 2014 10:15 AM -10:45 AM

Location: Behind modules and Longhouse on TESC, 47.0730° N, 122.9762° W

Photo by: Melisa Pinnow. Nov. 15 2014

Small group of kinglets foraging together on some sort of pine tree when I arrive. They are about 12 m high in the branches and I see three of them. Their microhabitat includes moss and dead leaves, cones and needles. As they forage, the birds consistently vocalize, jumping and hopping from different branches. Twice during this observation did I see the flycatching maneuver displayed and it was quite amazing. In the picture taken by fellow classmate, Melisa Pinnow, you can see this maneuver in action. The bird will hover in front of a leaf or twig and prod or glean to find the delicious insects. The most common attack maneuvers I identified: leaf-gleaning and twig-gleaning.

November 19, 2014 12:05 PM – 1:30 PM

Location: Entrance to Organic Farms trail, 47.0730° N, 122.9762° W

Weather: Clear skies

I can hear the same pitched call and I block out all other bird sounds around me to find this kinglet I know I heard. Right next to the entrance of the trailhead, I can see movement on branches as I approach. I found a Golden-crowned Kinglet in a flock of Black-capped Chickadees! Seems to be 3 chickadees, one kinglet, and what looks to be a Pacific Wren trailing below on the ground. The kinglet makes short ‘te’ sounds as it forages amongst the others. It would make short hops from close branches and peck-probe the bark for invertebrates. The chickadees are more vocal than this kinglet. I keep following and see the kinglet wrapping its feet around branches and almost hanging to forage in hard to reach places. This kinglet is very acrobatic and seems to prefer eating while hanging. The chickadees are very energetic while the wren acts more as a shadow, collecting seeds as they fall to the ground from the other foraging going on above.

Like many birds, they are sensitive to human disturbances such as logging. However, the Golden-crowned Kinglet is not considered to be at risk; the population is slightly declining in the west, and somewhat increasing possibly due to reforestation of spruce trees in the northeast (Galati et al. 2012). In the journal article, Resistance of forest songbirds to habitat perforation in a high-elevation conifer forest, Ernest E Leupin, Thomas E Dickinson, and Kathy Martin experimented with the effect of forest removal in British Columbia on songbirds in the area. From their research, they found two species of songbird that showed “significant responses:” Regulus satrapa and Junco hyemalis (Dickinson T. et al, 2004). The kinglet population declined significantly post-harvest; the largest decline in a single treatment done by the team (treatment meaning a single forest removal experiment in one isolated area). The Junco population contrastingly responded positively post-harvest; the clearing of forest created more space for this songbird to build a larger community (Dickinson T. et al.) This experiment exhibits how some birds, like the Golden-crowned Kinglet, are more sensitive to changes in their environment than others that may even be in the same order, like the Dark-eyed Junco.

In 1949, scientists conducted a field experiment on the “Removal and Repopulation of Breeding Birds in a Spruce-Fir Forest Community,” using methods that highlight the forest community. Golden Crowned Kinglets as well as the American Crow and the Redbreasted Nuthatch were the only birds that had produced nestlings before the collect took place. This study took the male population from 370 males per 100 acres to 70 males per 100 acres (E. Stewart, W. Aldrich, 1951). Today, a scientific study on these birds is a bit less intrusive. Using microsatellite markers, scientist in Canada were able to track Regulus Satrapa to determine the plausibility that the Haida Gwaii region became a refuge for this species during the last ice age (Burg et al., 2014). In another current study, Mercury Bioaccumulation in Southern Appalachian Birds, assessed through feather concentrations, Regulus satrapa was a bird that was studied in the relationship between the high elevation in the Appalachians, the high deposition rates of mercury in the region, and the mercury contamination in wildlife (Buchwalter et al. 2014). Their findings showed that concentrations in juveniles were 17% higher than in adults within twelve of the 32 bird species tested, and most importantly mercury biomagnifies in birds within the Southern Appalachians with the main effects being trophic position proximity to water (Buchwalter et al. 2014). Finally, a 2013 study included golden-crowned kinglets in a study aimed at using bird species communities as indicators for site prioritization old growth forest restoration (Arcese and Schuster 2013). These kinglets were among 12 of 18 native species that were positive indicators of old-forest conditions and helped in the improving site prioritization for restoration. This study incorporated behavioral and demographic responses to variations in patch size, and proximity to human-used land (Arcese and Schuster 2013).

Arcese, P., Schuster, R. 2013. Using bird species community occurences to prioritize forests for old growth restoration. Ecography 36(4): 499-507).

Bent, C. A. 1949. Life histories of North American thrushes, kinglets, and their allies. U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull. 196.

Biodiversity Associates V. US Forest Service Department of Agriculture. 2002. 226 F Supp. 2d at 126-127. WY.

Birds.audubon.org. 2014. Golden-crowned Kinglet | National Audubon Society Birds. [online] Available at: http://birds.audubon.org/birds/golden-crowned-kinglet.

BirdWeb. 2014. Golden-crowned Kinglet. [online] Available at: http://216.119.85.42/BIRDWEB/bird/golden-crowned_kinglet#. Figure 1.

Buchwalter, D. B., Franzreb, K. E., Keller, R. H., Simons, T. R., Xie, L. 2014. Mercury bioaccumulation in Southern Appalachian birds, assessed through feather concentrations. Ecotoxicology 23(2): 304-316.

Dickinson T., Leupin, E., , Martin, K. 2004. Resistance of forest songbirds to habitat perforation in a high-elevation conifer forest. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 34(9): 1919-1928).

Charles R. Blem and John F. Pagels. 1984. Mid-Winter Lipid Reserves of the Golden-Crowned Kinglet. Condor 491-492.

Franzreb, Kathleen E. 1984. Foraging habits of Ruby-crowned and Golden-crowned Kinglets in an Arizona montane forest. Condor 139-145.

Galati R, Ingold J.L., Pattern M. 2012. Golden-crowned Kinglet (Regulus satrapa).The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology 301.

Kalinowski, T. 2012. Winter and the Golden-Crowned Kinglet. The Adirondack Almanack. [online] Available at: http://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2012/12/winter-and-the-golden-crowned-kinglet.html

Lukes, R. 2010. Door to Nature: The Golden-crowned Kinglet. The Pulse. [online] Available at: http://www.ppulse.com/Articles-c-2010-11-10-95992.113117-The-Goldencrowned-Kinglet.html

Melisa Pinnow. Nov. 15, 2014. Photo of Golden-crowned Kinglet. The Evergreen State College.

Naugler, C. 1993. Vocalizations of the Golden-Crowned Kinglet in Eastern North America. Journal of Field Ornithology 64: 346-351.

Rempel, R. S., Francis, C. M., Robinson, J. N. and Campbell, M. 2013. Comparison of audio recording system performance for detecting and monitoring songbirds. Journal of Field Ornithology, 84: 86–97.

Robert E. Stewart and John W. Aldrich. 1951. Removal and Repopulation of Breeding Birds in a Spruce-Fir Forest Community. The Auk 68:471-482.

Sibley, D. 2003. The Sibley field guide to birds of western North America. Page 336. New York: Knopf.

Swanson, D. L. 2007. Cold hardiness and summit metabolism in North American kinglets during fall migration. Acta Zoologica Sinica 53(4): 600-606.

T.M. Burg, S.A. Taylor, K.D. Lemmen, A.J. Gaston, V.L. Friesen. 2014. Postglacial population genetic differentiation potentially facilitated by a flexible migratory strategy in Golden-crowned Kinglets (Regulussatrapa). Canadian Journal of Zoology 92:163- 172.

Zlonis E. J. and Niemi, G. J. 2014. Avian Communities of Managed and Wilderness Hemiboreal Forests. Forest Ecology and Management 328: 26-34.

My name is Zoe Lovell and I am a Sophomore at The Evergreen State College. My focus is in zoology as well as environmental studies and I am currently enrolled in an Ornithology program. In my spare time I enjoy playing tennis, going on nature walks, and playing with my pet rats.

Leave a Reply