A Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) just after feeding, at the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge in Washington State on November 15th, 2012.

Great Blue Heron by Miles Micheletti is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Ardeidae

Genus: Ardea

Species: Ardea herodias

Introduction

The Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) is an unmistakable resident of many open areas near water. As the largest heron in North America, it measures around 46″ long, with a substantial wingspan of approximately 72″(Sibley 2003).

The foraging and nesting habits are variable between populations, with groups ranging up over 100 individuals per rookery (Seston & Zwiernik 2009). Great Blue Herons are carnivores that show a preference for fish, but will eat a wide variety of animals (Ajemian & Dolan 2011). While these herons show adaptability and resilience, they are nonetheless vulnerable to chemical contamination and the effects of human disturbance on foraging and nesting habitat (Baker and Sepulveda 2008) (Custer et al 2013) (Seston & Zwiernik 2009) (Stabins et al 2006).

Great Blue Herons can be found near water throughout North America year-round. In some areas populations of the bird are migratory. For example, in the upper Midwestern United States and much of central and eastern Canada, Great Blue Herons are residents during the summer breeding season, and move south to Mexico and Central America during the winter (See Figure).

Ardea herodias range map, compiled by NatureServe & WILDSPACETM

Range Map by NatureServe & WILDSPACETM is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Range Map Source

Great Blue Herons are usually found near water, which can include anything from a coastal beach to a muddy marsh or backyard water feature (Tenney 1995). Their habitat is often dictated by food availability; they will be more likely to occur somewhere with fish (Kelly et al 2008). They are, however, fairly omnivorous and as a result Great Blue Herons can be observed from larger open fields where they stalk small mammals to sheltered inland saltwater bays. On campus, observers will have the best chance of seeing them out on the beach itself at Eld Inlet, where the heron’s large size and distinctive neck shape can be from a distance. They particularly favor perches on floating platforms, posts, boats a few dozen yards offshore, or on higher, larger branches of beachfront trees. One can also go to near downtown Olympia to the lagoon and south end of Budd Inlet where it meets Capitol Lake, or Nisqually Wildlife Refuge.

Herons will nest in a wide variety of places, natural and artificial, in trees or on the ground. They prefer nests with protection or camouflage from ground predators, situated near water, so they will use trees if they’re available (Vennesland 2011), even going so far as to reuse unoccupied Osprey nests (Hansell 2000). Nest sites are chosen for their proximity to food, and their distance from human activity (Kelly et al 2008) (Vennesland 2010). Great Blue Herons will build colonies in proximity with other species, mainly other herons and egrets. They have also been found to choose sites near eagle,s since the eagles will defend that territory from mammals that predate on the heron hatchlings (Vennesland 2011) (Jones 2013).

Great Blue Herons maintain a carnivorous diet that is able to adapt to the food that is available. They will eat crustaceans, amphibians, reptiles, large insects, small mammals, and even other birds and their eggs and young (Vennesland & Butler 2010). Their diet, being so diverse, has been a subject of interest for many scientists.

There are records from an analysis of a dead heron’s throat where scientists found Western Pond Turtle hatchlings (Niemala 2012). In another article a heron was observed catching an Atlantic Stingrays and eating it (Ajemian 2011). James W. Rivers and Michael J. Keuhn describe, in the Wilson Journal of Ornithology (2006), observations of a Great Blue Heron killing and attempting to eat an Eared Grebe, although it was unable to do so (Rivers & Kuehn 2006).

At all times of day and night during low tide, herons have been observed foraging and active (Black and Collopy 1982). Great Blue Herons are often described as patient hunters. Great Blue Herons’ distinctive long neck is well adapted for making extremely fast strikes at prey (Vennesland & Butler 2010). This particular style of hunting is referred to as ‘sit-and-wait.’ Sometimes, after catching larger fish, a Great Blue Heron, will wait to swallow until it is on shore (Tenney 1995).

Great Blue Herons have also been observed near Atlantic bottlenose dolphins using a technique called strand-feeding. The dolphins hunt by charging towards a shallow bank, It temporarily strands itself, along with any fish that were caught in the dolphin’s bow wave. Ardeids including the Great Blue Heron benefit from these stranded fish enough that they will favor the areas where dolphins are strand feeding over other pieces of beach (Fox 2012).

A Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) catching a rodent in the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge in Washington State on November 15th, 2012.

Great Blue Heron by Miles Micheletti is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Great Blue Heron

In this recording, a Great Blue Heron is arguing with a Double-crested Cormorant over a prime perch just offshore of the northernmost point of Geoduck Beach, on October 23, 2012. The Cormorant’s calls, near the end of the recording, are noticeably sharper and higher than the Great Blue Heron’s.

In the sound bite below is of when one Great Blue Heron flew in the direction of a second Great Blue Heron’s position in the grasses at Nisqually Wildlife Refuge wetland and they flew together for a few seconds. The first call comes from the first heron, and the second from the heron who was in the grasses. The first an adult, the second a juvenile.

The call of a Great Blue Heron can sound similar to that of a Mallard Duck. This recording can help one distinguish between the two. First is the Mallard Duck and then the Great Blue Heron call is at the end, with a different quality, more of a “grawk,” and lower pitched

Another example of a Great Blue Heron call, more distinguished from other birds when it goes through this range of pitches and qualities.

Great Blue Herons are partial migrants; the northernmost populations will leave their breeding areas when food becomes scarce. The herons on the Evergreen campus, and throughout the Pacific Northwest, are non-migratory, as food resources remain plentiful throughout our mild winters. In general, Great Blue Herons are usually seen alone, apart from their nests, which are gathered in small colonies known as “heronries”, and sometimes when they migrate in small flocks (Vennesland & Butler 2010).

They are usually observed standing completely still or wading slowly and deliberately, breaking the lull instantaneously as they swiftly seize prey. Equally slow and calm is their flight, as a result of their long legs, large wings, and distinctively curved necks. During the breeding season this personality trait is coupled with breeding displays including everything from large circular flights with neck extended, to ‘the stretch’, wherein a male extends its bill vertically, calls, and then drops its head and bill forward and down (Vennesland & Butler 2010).

Conservation

Climate change, population growth, and pollution pose a threat to Great Blue Herons. A study of waterbirds described in the Canadian Journal of Zoology found that Great Blue Herons were more sensitive to the environmental changes caused by human industry and recreation than nearly all other birds surveyed, which included a wide variety of ardieds (Webb 2008). James A. Rodgers and Stephen T. Schwikert suggest a buffer zone of 180 meters for personal water craft and outboard-motor powered boats to protect Great Blue Herons and other wading birds in the February 2002 issue of Conservation Biology. The largest impact on Great Blue Heron populations comes from loss of habitat due to human disturbance, particularly in nesting sites and key feeding areas. As human influence expands, nesting and foraging sites are at risk of degradation and fragmentation (Eissinger 2007).

When Great Blue Herons decide where a rookery will be, the decision is made almost entirely by how suitable the foraging site is in the surrounding kilometer (Kelly et al 2008). This is an important factor in looking at how herons may cope with climate change, since the hypothesized changes would negatively affect foraging areas. In a recent study on Great Blue Herons’ resilience to climate change the authors found that decline in good foraging sites would decrease heron’s reproductive success in the long term (Kelly and Condeso 2014). Entire groups of herons have been observed to abandon their rookery in favor of ones with less human disturbance. This becomes increasingly problematic as the number of nesting sites are reduced and the populations in those that are left consist of a large number of individuals (Vennesland 2010). Studies have also shown that when herons leave their nesting sites, which is most often due to human disturbance, the nests are less productive (Vennesland and Butler 2004).

Chemical contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and organochlorine pesticides have been found to negatively impact an egg’s success and these have been found in the yolks of Great Blue Heron eggs (Baker and Sepulveda 2008). Perfluorinated compounds which were used in a wide variety of commercial products also are a threat to Great Blue Herons reproductive health but since their ban in 2000 studies have shown a decrease in heron’s exposure to the chemicals (Custer et al 2013). Chemical threats have not been entirely eradicated, there is still possible contamination in the Delaware Bay and Coastal regions of Oregon and Washington (Thomas & Anthony 1999). Additionally, new chemicals such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) may threaten the species and have been found increasingly in the tissues of some populations in British Columbia (Elliot et al 2005). Harmful Karenia Brevis algal blooms in 2013 caused fatal Brevetoxicosis in Great Blue Herons (Fauquier 2013).

Great Blue Herons can be beneficial to the conservation of other species as well. The advantages of using them for ecological risk assessments (which help determine the effects of contaminants in a given area) are explained in the abstract of “Utilizing the great blue heron (Ardea herodias) in ecological risk assessments of bioaccumulative contaminants” from the Environmental Monitoring & Assessment journal (Seston 2009). The authors make a case that Great Blue Herons are important for the preservation of species other than themselves since they are more sensitive to toxic chemicals by their specific biology and foraging practices. This risk of exposure paired with their widespread distribution makes them a species that can be studied in many habitats and geographical location.

Population

Great Blue Herons have rebounded since the early 1960’s, though current population trends are not consistent. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data shows a slight decline (P <0.0001) in the population in the last two decades (Fig. 1). This is likely due to the overall decline in productivity exhibited in British Columbia (Vennesland & Butler 2008). In Washington state, the BBS data shows a slight gradual decline (P=0.0034) (Fig. 2).

Heron “4” seen at Nisqually 11/20. Note white crown and dark blue scapulars.

Photographer: Karla Kelly

Heron “2” seen at Nisqually 11/20. Note dark crown and brownish grey scapulars.

Photographer: Karla Kelly

10:45 am West Bay Olympia WA (small lagoon on west side) 47.045N 122.911W

Weather: 48°F, Clear sky, Breeze, 5mph

I am sitting on a bit of old railroad track trestle looking west over the lagoon. First I saw single GBH sitting on dead branch over the water. After a period of time more individuals flew into area. I numbered them according to order I saw them in. Watched for 2.5 hours.

| Time | Individual | Action (if any) | Position (if changed) | Category | Location |

| 10:45 | 1 | 3m from ground, dead branch over land and lagoon | 1 | ||

| 11:05 | 2 | Flew to ground with call | On ground under canopy and 1 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 11:05 | 3 | Flew to log with call | Log 1m over water 20m South of 2 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 11:05 | 4 | Flew to tree with call | Tree branch 6m from ground 10m South of 3 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 11:08 | 5 | Heard call and I assumed landing | East side of bank | Fly with call | 1 |

| 11:11 | 5 | Call and flew over me and landed | Tree 70, south of 4, 12, above ground | Fly with call | 1 |

| 11:16 | 3 | Preened back | Preen | 1 | |

| 11:20 | 3 | Preened under wing | Preen | 1 | |

| 11:23 | 5 | Preened breast (for 4mins) | Preen | 1 | |

| 11:27 | 2 | Preened breast | Preen | 1 | |

| 11:37 | 6 | East side of lagoon on grasses 30m north of me | 1 | ||

| 11:37 | 7 | East side of lagoon on grasses 10m north of 6 | 1 | ||

| 11:39 | 8 | North side of lagoon 50m north of 7 | 1 | ||

| 11:40 | 9 | North side of lagoon 10m west of 8 | 1 | ||

| 11:46 | 1 | Reached out at ivy on branch and grabbed with beak | Forage | 1 | |

| 11:50 | 6 | Sat down in grass | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:00 | 10 | Flew to ground with call | East side of lagoon on mud 3m southwest of 6 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 12:00 | 11 | Flew to ground with call | East side of lagoon <1m from 10 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 12:04 | 12 | Flew to ground with call | East side of lagoon 2m east of 11 and 10 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 12:04 | 13 | Flew to ground with call | East side of lagoon <1m from 12 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 12:10 | 3 | Flew over lagoon to ground with call | East side of lagoon 2m east of 6 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 12:15 | 14 | Flew to ground with call | East side of lagoon <1m from 3 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 12:16 | 14 | Opened wings and outstretched neck | Position of 3 | Interact | 1 |

| 12:16 | 3 | Opened wings and walked away | 1m south of 13 | Interact | 1 |

| 12:20 | 15 | Flew to ground with call | East side of lagoon 3m south of 3 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 12:25 | 13 | Walked east towards 14 | Walk | 1 | |

| 12:25 | 14 | Call and walked east 1-2m and north towards 6 | Interact | 1 | |

| 12:30 | 6 | Flew north up bank | About 3m north of original position | Fly | 1 |

| 12:34 | 6 | Sat down in grass | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:40 | 3 | Flew to north side of 10 | 1m north of 10 | Fly | 1 |

| 12:44 | 11 | Walked east 2m | Walk | 1 | |

| 12:45 | 6 | Laying down | 1 | ||

| 12:45 | 7 | Neck up (has been entirity of observation) | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:45 | 10 | Down | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:45 | 11 | Down | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:45 | 12 | Up | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:45 | 13 | Up | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:45 | 14 | Down | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:45 | 15 | 1/2 Up | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:50 | 2 | Reached out and grabbed at reeds | Forage | 1 | |

| 12:53 | 2 | Walked out in water | 4m north 2m east of original position | Walk | 1 |

| 12:55 | 2 | Reached out neck and hovered head above water surface then struck with beak | Forage | 1 | |

| 12:55 | 3 | Flew over lagoon to ground near original log | 15m north of 4 | Fly | 1 |

| 1:05 | 3 | Flew over lagoon in long arc with call | Original position of 7 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 1:05 | 7 | Flew over lagoon in long arc with call doing a kind of spiral with 3 | Into trees on west side of lagoon | Fly with call | 1 |

| 1:20 | 3 | Defecated while flying west across lagoon | Into trees on west side of lagoon | ||

3:30pm West Bay Olympia WA (small lagoon on west side) 47.045N 122.911W

Weather: 45°F Calm, mostly cloudy

Looking over the lagoon and West bay from the 4th avenue bridge and saw GBH and then went down under the bridge to the same elevation as the lagoon. Watched it for about 35mins. It preened its chest and underwing. It was perched on the west side of the bank on a log 1m over the water. It looked around when there was another GBH that flew north to south over the bay calling. A flock of Canada Geese flew over and it also looked around. I went over to the east side of the bank and watched what I think was the same GBH that called fly north to south over the 4th avenue bridge. I noticed at 4:17 another GBH on some rocks between the very south end of the bay and Capitol Lake. It walked only a few steps within the 20 minutes I watched it.

11/19/14

4:02pm West Bay Olympia WA (small lagoon on west side) 47.045N 122.911W

Weather: 43°F 5mph wind, clear

Spotted one GBH, with white coloring on breast and nape, looks like #1 I saw on the 10th, because of all the white. Watched for 1.75 hours.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

10:35am Nisqually Refuge 47.079N 122.70917W On path near observatory

Weather: 44°F No wind, ½ cloud cover

I again listed individuals with numbers according to when I saw them, but I am not sure of overlap in this case. (aka, 1 could be 4) Watched for 2 hours.

| Time | Individual | Action (if any) | Position (if changed) | Category | Location |

| 10:30 | 1 | 40m north of path in grasses, neck outstreatched | 2 | ||

| 10:36 | 2 (juvenile) | 10m north of path, 50m west of 1, eye facing me | 2 | ||

| 10:37 | Caroline | played GBH call | 10m south of 2 | 2 | |

| 10:37 | 2 | Stretched out neck, opened wings and body tipped forward onto grass, rose up with rodent the size of beak in beak | Forage | 2 | |

| 10:38 | 2 | Opened and closed beak about 5 times on rodent and swallowed within 5 seconds | 2 | ||

| 10:40 | 2 | Walked west on side of trail, followed by us | Walk | 2 | |

| 10:43 | 2 | When we got closer neck went all the way down and body tipped forward with walking, feathers on back raised | 2 | ||

| 10:50 | Caroline | played GBH call | 10m south of 2 | 2 | |

| 10:51 | 2 | Stretched out neck, swiveled head, then flew south east and called | 50m south of trail, 50m east of us | Fly with call | 2 |

| 10:54 | 3 (juvenile) | 5m east of 2 original location, 30-50m south of trail, neck outstretched, in grasses | 2 | ||

| 10:55 | 4 | 20m west of 3, 2m north of trail, neck scrunched | 2 | ||

| 10:58 | 4 | walked south | Few inches north of trail | Walk | 2 |

| 11:00 | 4 | flew south east with call | Fly with call | 2 | |

| 12:20 | 5 | 2m north of trail | 2 | ||

| 12:28 | 5 | had rodent size of beak in beak, closed beak 3 times then swallow | Forage | 2 | |

2:00pm Nisqually Refuge 47.079N 122.70917W On path looking over pond

Weather: 45°F 15mph wind, drizzling

I again listed individuals with numbers according to when I saw them, but I am not sure of overlap in this case. (aka, 1 could be 4) Watched for 1.5 hours.

| Time | Individual | Action (if any) | Position (if changed) | Category | Location |

| 1:20 | 1 | On log on pond | Rest | 2 | |

| 1:25 | 1 | Put neck down | 2 | ||

| 1:45 | 2 | Flew in arc over reeds east of observation area | Fly | 2 | |

| 2:00 | 3 | Flew in arc over reeds east of observation area and called | Landed over 100m east of observation area in grass | Fly | 2 |

| 2:20 | 4 | In reeds 35m south of trail | 2 | ||

| 2:25 | 5 | Fly | |||

| 2:25 | 5 | Flew towards 4 | Interact | 2 | |

| 2:25 | 4 | Fly | |||

| 2:25 | 4 | Flew up and circled around with 5, both called | Disappeared in grasses South east of original position | Interact | 2 |

| 2:26 | 5 | Landed in grasses | In orginal position of 4 | 2 | |

| 2:30 | 5 | Took step west into thicker grass | Walk | 2 | |

| 2:35 | 5 | Raised neck, swiveled head | 2 | ||

| 2:40 | 6 | Perched on top 20m tall snag, 50m north of trail | Rest | 2 | |

| 2:46 | 7 | Flew up from reeds in arc anded disappeared back into reeds | 40m NE of 6 then 40m W of 6 | Fly | 2 |

| 2:50 | 7 | Flew up from reeds in arc anded disappeared back into reeds | 100m W of 6 | Fly | 2 |

12:45pm West Bay Olympia WA (small lagoon on west side) 47.045N 122.911W

Weather: 35°F 5mph wind, sunny

Individuals listed in order seen. Watched for 1 hour.

| Time | Individual | Action (if any) | Position (if changed) | Category | Location |

| 12:45 | 1 (adult) | On bridge | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:47 | 2 (juvenile) | 30m north of 1 on bank | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:48 | 3 (adult) | 1m ne of 2 | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:48 | 4 | 3m north of 2 | Rest | 1 | |

| 12:49 | 5 | resting | far north side of lagoon | Rest | 1 |

| 12:49 | 6 | resting | 2m west of 5 | Rest | 1 |

| 1:00 | 1 | neck curled | 1 | ||

| 1:00 | 2 | neck curled | 1 | ||

| 1:00 | 3 | neck curled | 1 | ||

| 1:00 | 4 | neck curled | 1 | ||

| 1:00 | 5 | neck curled | 1 | ||

| 1:00 | 6 | neck curled | 1 | ||

| 1:02 | 2 | facing 3 neck outstretched | Interact | 1 | |

| 1:02 | 3 | facing 2 neck less outstretched | Interact | 1 | |

| 1:05 | 1 | preening breast, side, neck | Preen | 1 | |

| 1:07 | 2 | neck outstretched | 1 | ||

| 1:07 | 3 | neck outstretched | 1 | ||

| 1:07 | 4 | neck outstretched | 1 | ||

| 1:09 | 1 | stretching wing and preening | 1 | ||

| 1:10 | 1 | flew with call | 2 m south of 2 | Fly with call | 1 |

| 1:11 | 1 | walking slowly south | Walk | 1 | |

| 1:11 | 1 | preening breast, side, neck | Preen | 1 | |

| 1:15 | 7 | flew high over 4th ave bridge and lagoon with call | Fly with call | 1 | |

| 1:17 | 3 | neck outstretched over water | 1 | ||

| 1:17 | 3 | lunged into water, front of body in water | Forage | 1 | |

| 1:17 | 3 | standing back on land, can’t see anything in beak, rustled feathers | 1 | ||

| 1:19 | 2 | walked east towards reeds then walked back | Walk | 1 | |

| 1:19 | 2 | nipped at water | Forage | 1 | |

| 1:20 | 2 | walked east towards reeds nipped at reeds | Forage | 1 | |

| 1:20 | 2 | step towards 4 neck half up | Interact | 1 | |

| 1:20 | 4 | neck down | Interact | 1 | |

| 1:22 | 1 | preening sides | 1 | ||

| 1:22 | 2 | flew onto log in water | 2ft from bank | Flew | 1 |

| 1:22 | 2 | scratching head | Preen | 1 | |

| 1:25 | 2 | reached into water with beak | Forage | 1 | |

| 1:30 | 1 | resting | Rest | 1 | |

| 1:30 | 4 | resting | Rest | 1 | |

| 1:30 | 3 | resting | 1 | ||

| 1:33 | 2 | nipped at water | Forage | 1 | |

| 1:35 | 1 | preening breast | Preen | 1 | |

2:25pm West Bay Olympia WA (small lagoon on west side) 47.045N 122.911W

Weather: 34°F 5mph wind, sunny

Individuals listed in order seen. Watched for 1 hour.

| Time | Individual | Action (if any) | Position (if changed) | Category | Location | ||

| 2:25 | 1 (adult) | west side of lagoon 2m above water on dead branch | 1 | ||||

| 2:25 | 2 (juvenile) | 10m north of 2, 2m above water on dead branch | 1 | ||||

| 2:25 | 3 (adult) | 2m above 2 on dead branch | 1 | ||||

| 2:25 | 4 (adult) | 4m from 2 and 3, 4m above water on dead branch | 1 | ||||

| 2:25 | 5 | 7m from 4, 3m above water on dead branch | 1 | ||||

| 2:35 | 5 | Flew over water | 2 m north of 1 | Fly | 1 | ||

| 2:37 | 4 | Stretcing legs | Preen | 1 | |||

| 2:37 | 4 | Preening chest on one leg | 1 | ||||

| 2:38 | 1 | Beak pointing SE | Rest | 1 | |||

| 2:38 | 5 | Beak pointing S | Rest | 1 | |||

| 2:38 | 2 | Back to me (beak W) | Rest | 1 | |||

| 2:38 | 3 | Beak pointing S | Rest | 1 | |||

| 2:38 | 4 | Beak pointing S | Rest | 1 | |||

| 2:40 | 5 | Flew over water landed by keeping legs straight pointing towards perch and flapped to land steady on perch | Log sticking out of water | Flew | 1 | ||

| 2:41 | 4 | Flew over water | Below 2 on dead branch <1ft above water | Flew | 1 | ||

| 2:42 | 4 | Walking on branch towards bank | Walk | 1 | |||

| 2:46 | 6 (adult) | 4m north of 3 on dead branch, concealed by cedar branches | Rest | 1 | |||

| 2:46 | 7 (juvenile) | 5m north of 3 on dead branch concealed by cedar branches | Rest | 1 | |||

| 2:47 | 6 | Moving beak stretching neck | Preen | 1 | |||

| 2:49 | 5 | Lifting legs up, stretching, preening breast | Preen | 1 | |||

| 2:51 | 8 | 30 m N of 7 on dead branch 1.5m above water | 1 | ||||

| 2:52 | 8 | Preening sides and chest | Preen | 1 | |||

| 2:54 | 5 | Preening | 1 | ||||

| 2:54 | 4 | Sitting beak S | Rest | 1 | |||

| 2:54 | 2 | Sleeping | 1 | ||||

| 2:54 | 3 | Sitting | 1 | ||||

| 2:54 | 6 | Intermittent preening | 1 | ||||

| 2:54 | 7 | Sitting | 1 | ||||

| 2:54 | 8 | Preening | Preen | 1 | |||

| 3:15 | 5 | Beak pointing S | 1 | ||||

| 3:15 | 1 | Beak pointing S | 1 | ||||

| 3:15 | 4 | head down under wing | 1 | ||||

| 3:15 | 2 | head down under wing | 1 | ||||

| 3:15 | 3 | Beak pointing E | 1 | ||||

| 3:15 | 6 | Beak pointing S | 1 | ||||

| 3:15 | 7 | Beak pointing N | 1 | ||||

| 3:15 | 8 | Beak pointing S | 1 | ||||

| 3:25 | 2 | preening side | Preen | 1 | |||

| 3:25 | 4 | moving head and beak, back towards me | 1 | ||||

2:45pm Nisqually Refuge 47.079N 122.70917W On path looking over tide pools

Weather: 43°F 5mph wind, partly cloudy

Numbered in order seen. Watched for 1.75 hours.

| Time | Individual | Action (if any) | Position (if changed) | Category | Location |

| 2:45 | 1 (juvenile) | Walking slowly down path | 2m L of path | Walk | 2 |

| 2:47 | 1 | Walking with head down towards ground | 2 | ||

| 2:49 | 2 | Flying over path in large arc back to landing R side of path | Somewhere R of path | Fly | 2 |

| 2:53 | 1 | Moving grasses aside with beak, walking into denser grasses, away from people walking down path | 2 | ||

| 3:00 | 1 | Still slowly walking, head bobbing with each step | 2 | ||

| 3:03 | pedestrian | Walked up past 1 | 2 | ||

| 3:03 | 1 | Walked slightly faster then slowed down | 2 | ||

| 3:20 | 3 (adult) | Neck outstretched walking further from bank | In tide pool on right of path, knee deep | Walk | 2 |

| 3:24 | Truck | drives down path | 2 | ||

| 3:24 | 3 | Neck curled | 2 | ||

| 3:25 | 3 | Stuck tip of beak into water then shook head | Forage | 2 | |

| 3:26 | 3 | Continues walking into water beak facing down | Walk | 2 | |

| 3:28 | 3 | Walking into deeper water, head moves back and forth quickly | 2 | ||

| 3:38 | 4 (adult) | Flys over from east to tide pool | 30m E of 3 | Fly with call | 2 |

| 3:38 | 3 | Looked over towards 4 | 2 | ||

| 3:41 | 3 | Stuck tip of beak into water then shook head | Forage | 2 | |

| 3:48 | 3 | Walked backwards a few steps | Walk | 2 | |

| 3:55 | 5 | Flew in distance north | Fly | 2 | |

| 4:05 | 6 | Flew low over water | Fly | 2 | |

| 4:07 | 3 | Stuck tip of beak into water then shook head | Forage | 2 | |

| 4:10 | 3 | Standing still with neck down | 2 | ||

| 4:15 | 3 | Stalking towards water head forward | Walk | 2 | |

| 4:20 | 2 | Same place as before taking slow steps | Walk | 2 | |

| 4:25 | 2 | Stopped walking | 2 | ||

| 4:25 | me | walked past 2 | 2 | ||

| 4:26 | 2 | Started walking again | 2 | ||

5pm West Bay Olympia WA East side under 4th ave bridge 47.045N 122.911W

Weather: 45°F 5mph wind, dark partly cloudy

Watched and listened for sounds for from 5-8pm. Saw none foraging and heard calls 4 times. One at 5:30, one at 6:02, another at 6:10, and another at 7:10. All calls were while they were flying overhead from west to east and the third call from north to south.

Watched one GBH for 30mins foraging below Bayview Thriftway dock.

| Time | Individual | Action (if any) | Position (if changed) | Category | Location |

| 9:30 | 1 | <1m from bank on east side of Budd inlet | 1 | ||

| 9:35 | 1 | Head poised over water | 1 | ||

| 9:40 | 1 | Took step into water | Walk | 1 | |

| 9:43 | 1 | Reached with beak and quickly stabbed water | Forage | 1 | |

| 9:43 | 1 | Walked back onto bank with beak poised up | 1m east of original position | Walk | 1 |

| 9:44 | 1 | Swallowed | 1 | ||

| 9:48 | 1 | Walked back into water | Back to original position | Walk | 1 |

| 9:51 | people | Walked onto dock above 1 while talking | 1 | ||

| 9:51 | 1 | Flew with call south | Landed below bridge on rocks at base 1m from water | Fly with call | 1 |

| 9:53 | 1 | Took a couple steps on rocks | Walk | 1 | |

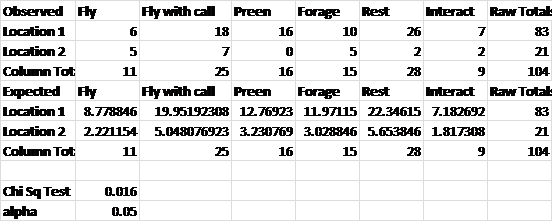

I noticed some differences in the activity I observed at the two sites so I ran a chi square test to see if it was a statistically significant value. The results are in the below table.

Location 1 is the West Bay site and Location 2 is Nisqually Wildlife Refuge. A Chi Square test found that the difference between the observed behavior of Great Blue Herons at the two sites is statistically significant.

My possible explanations for the differences observed are the type of habitat I observed, and the human disturbance. At Nisqually there were open fields and shallower water. There was a lot more land I was looking at as well around Nisqually. At the West Bay site I could see the birds resting because there were less good hiding places, especially those with good foraging possibilities, where at Nisqually herons could easily be foraging or just resting in the tall grasses and I wouldn’t have seen them.

The human disturbance I propose as a factor is that I often saw herons that were reacting to me or other humans at Nisqually, but at West Bay behavior didn’t seem to change as I approached my observation area.

I also noticed that foraging behavior at Nisqually was higher at low tide, but at West Bay, tide didn’t seem to be a large factor. At the West Bay site the water was affected largely by the opening and closing of the dam at Capitol Lake, which created current, and that was when I often saw foraging. If I had more time I would have looked into the dam and times when it opens and closes to test out this hypothesis.

Ajemian, M. J., Dolan, D., Graham, W. M., & Powers, S. P. (2011). First Evidence of Elasmobranch Predation by a Waterbird: Stingray Attack and Consumption by the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias). Waterbirds, 34(1), 117-120.

Audubon, J. J. (1827). The Birds of America; from original drawings by John James Audubon. London, England: Self-published. Retrieved from http://web4.audubon.org/bird/BOA/F38_G1g.html

Azerrad, J. M. 2012. Management recommendations for Washington’s priority species: Great Blue Heron. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia, Washington.

Baker, S., & Sepúlveda, M. (2008). An evaluation of the effects of persistent environmental contaminants on the reproductive success of Great Blue Herons (Ardea herodias) in Indiana. Ecotoxicology, 18(3), 271-280.

Bancroft, G. T. 1989. Status and conservation of wading birds in the Everglades. American Birds, 43, 1258-1265.

Black, B., & Collopy, M. (1982). Nocturnal Activity of Great Blue Herons in a North Florida Salt Marsh. Journal of Field Ornithology, 53(4), 403-406.

Crozier, G. E., & Gawlik, D. E. 2003. Wading bird nesting effort as an index to wetland ecosystem integrity. Waterbirds, 303-324.

Custer, T., Dummer, P., & Custer, C. (2013). Perfluorinated compound concentrations in great blue heron eggs near St. Paul, Minnesota, USA, in 1993 and 2010-2011. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 32(5), 1077-1083.

Elliott, J. E., Wilson, L. K., & Wakeford, B. 2005. Polybrominated diphenyl ether trends in eggs of marine and freshwater birds from British Columbia, Canada, 1979-2002. Environmental science & technology, 39(15), 5584-5591.

Eissinger, A.M. 2007. Great Blue Herons in Puget Sound. Puget Sound Nearshore Partnership Report No. 2007-06. Published by Seattle District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle, Washington.

Fauquier, D., Flewelling, J., Maucher, J., & Keller, M. (2013). Brevetoxicosis in seabirds naturally exposed to Karenia brevis blooms along the central west coast of Florida. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 49(2), 246-60.

Fox, A. G., & Young, R. F. 2012. Foraging interactions between wading birds and strand-feeding bottlenose dolphins ( Tursiops truncatus) in a coastal salt marsh. Canadian Journal Of Zoology, 90(6), 744-752. doi:10.1139/z2012-043

“Great Blue Heron.” All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Web. 6 Nov 2012. <http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Great_Blue_Heron/id>.

Hansell, M. 2000. Bird nests and construction behavior. (Hardback edition ed.). Cambridge: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Jones, I., Butler, R., & Ydenberg, R. (2013). Recent switch by the Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias fannini in the Pacific northwest to associative nesting with Bald Eagles ( Haliaeetus leucocephalus) to gain predator protection. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 91(7), 489-489.

Kelly, J., Stralberg, D., Etienne, K., & McCaustland, M. (2008). Landscape influence on the quality of heron and egret colony sites. Wetlands, 28(2), 257-275.

Kelly, J.P. and Condeso, T.E. 2014. Rainfall Effects on Heron and Egret Nest Abundance in the San Francisco Bay Area. Wetlands: 1-11.

Kerlinger, P. 2002. Out of the Blue. Birder’s World, 16(6), 86.

Niemela, S. A., & Bury, R. 2012. Hatchlings of the western pond turtle (Actinemys marmorata) in diet of Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias). Northwestern Naturalist, 93(1), 84-85.

Pyle, P., & Howell, S. (2004). Ornamental Plume Development and the “Prealternate Molts” of Herons and Egrets. The Wilson Bulletin, 116(4), 287-292.

Rivers, J. W., & Kuehn, M. J. 2006. Predation of Eared Grebe by Great Blue Heron. Wilson Journal Of Ornithology, 118(1), 112-113.

Rodgers, J. A., & Schwikert, S. T. 2002. Buffer-Zone Distances to Protect Foraging and Loafing Waterbirds from Disturbance by Personal Watercraft and Outboard-Powered Boats. Conservation Biology, 16(1), 216-224. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00316.x

Seston, R. M., Fredricks, T. B., Tazelaar, D. L., Coefield, S. J., Bradley, P. W., Newsted, J. L., & … Zwiernik, M. J. 2010. Tissue-based risk assessment of great blue heron (Ardea herodias) exposed to PCDD/DF in the Tittabawassee River floodplain, Michigan, USA. Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry, 29(11), 2544-2558. doi:10.1002/etc.319

Seston, R., Zwiernik, M., Fredricks, T., Coefield, S., Tazelaar, D., Hamman, D., & … Giesy, J. 2009. Utilizing the great blue heron ( Ardea herodias) in ecological risk assessments of bioaccumulative contaminants. Environmental Monitoring & Assessment, 157(1-4), 199-210. doi:10.1007/s10661-008-0528-7

Sibley, David Allen. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. 1st edition 3rd printing. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003. Print.

Sibley, David Allen. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior. 1st Flexbind edition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001. Print.

Stabins, A., Raedeke, K., & Manuwal, D. (2006). Productivity of Great Blue Herons in King County, Washington. Northwest Science, 80(2), 116-118.

Tenney, B., & Pellegrini, S. 1995. Fishing for dinner. Conservationist, 49(6), 32.

Thomas, C. M., & Anthony, R. G. 1999. Environmental contaminants in great blue herons (Ardea herodias) from the lower Columbia and Willamette Rivers, Oregon and Washington, USA. Environmental toxicology and chemistry, 18(12), 2804-2816.

Vennesland, R., & Butler, R. (2004). Factors Influencing Great Blue Heron Nesting Productivity on the Pacific Coast of Canada from 1998 to 1999. Waterbirds, 27(3), 289-296.

Vennesland, R.G. and Butler, R.W. 2008. COSEWIC Assessment and update status report on the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias fannini) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada , Ottawa, Ontario.

Vennesland, R.G. 2010. Risk perception of nesting Great Blue Herons: experimental evidence of habituation. Canadian Journal of Zoology 88:81-89.

Vennesland, Ross G. and Robert W. Butler. 2011. Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/025

Webb, S. M., Boyce, M. S., & Found, C. C. 2008. Selection of lake habitats by waterbirds in the boreal transition zone of northeastern Alberta. Canadian Journal Of Zoology, 86(4), 277-285. doi:10.1139/Z07-137

Like the birds, Miles Micheletti is very awkward and has legs that are quite long, which would certainly give him an advantage foraging in water if he did, in fact, forage in water, which he usually doesn’t.

Field notes and edits by Annie Cantrell in Fall 2014. She likes watching the herons.

A Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) taking flight in the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge in Washington State on November 15th, 2012.

Great Blue Heron by Miles Micheletti is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Leave a Reply