Order: Podicipediformes

Family: Podicipedidae

Genus: Podiceps

Species: Podiceps auritus

Introduction

Podiceps auritus, or the Horned Grebe, is a small migratory waterbird that averages around 13 inches in length and weighs around 1lb (Konter 2001). It has a long neck and a darkly colored, short, thin, pointed bill with a light-colored tip (Stedman 2000). This grebe is most familiar to the people of the Pacific Northwest while in its winter plumage (pictured above), at which time it can be identified by its bright white throat, cheeks, chest, and underbelly with contrasting dark brownish black sides, back, and crown area. The flashes of white make the bird very visible against the water, but due to the fact that they spend most of the day so far from shore binoculars are almost always necessary in order to make a positive identification (Pers. Obs; Stedman 2000).

By Mark Medcalf (Red Eye Uploaded by snowmanradio) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

- © NatureServe

Supplier: Birds of DC, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

Source: NatureServe

Editor: Birds of DC

Ridgely, R. S., T. F. Allnutt, T. Brooks, D. K. McNicol, D. W. Mehlman, B. E. Young, and J. R. Zook. 2007. Digital Distribution Maps of the Birds of the Western Hemisphere, version 3.0. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia, USA.

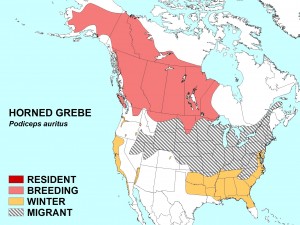

The Horned Grebe has what is called a northern Holarctic distribution, this means that their range extends throughout the Northern hemisphere, primarily in the boreal climatic zone and occasional in the tundra, temperate, and steppe areas (Fjeldsa 1973). They are a migratory waterfowl, so the distribution varies throughout the year depending on the season. In North America, the breeding range extends from southern to central Alaska and throughout most of Canada. Small populations have been found to breed elsewhere in North America as far south as Oregon, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Minnesota. The Horned Grebe’s winter range is mostly along the coasts, but there are some populations that can be found inland on large lakes, rivers, or resevoirs. On the Pacific coast, its winter range stretches from Aleutian Bays, Alaska to the Gulf of California (Stedman 2000). It is during the winter season that they can be found in the Puget Sound Estuary and will then become a part-time resident on the Evergreen campus. They can be found off the shoreline of the Evergreen beach in Eld Inlet, and although common, they are not an overly abundant visitor (Pers. Obs.). On the Atlantic coast, the winter range will stretch from southern Novia Scotia all the way to southern Florida, some smaller numbers can even be found farther west through the gulf into Texas (Stedman 2000).

Breeding Habitat

The Primary breeding habitats for Horned Grebes in North America are small to mid-sized freshwater marshes and ponds, ranging in size from smaller-0.05 hectares to mid-sized 1-10 hectares, ideally with large mats of floating vegetation (Stedman 2000). The floating vegetation is an important aspect in their chosen breeding habitat because those areas are used as mating and nest building sites due to Grebe’s lack of mobility on land. They arrive on their breeding grounds in late-April to early-May, after which mated pairs will quickly establish territories. There are certain abiotic factors that are important for creating the ideal habitat for the Horned Grebes during their mating season; they tend to prefer larger, permanent wetlands rather than ephemeral (or non-permanent) with deeper water, and more densely vegetated surroundings. Biotic factors such as competition come into play with habitat selection as well, and can often result in pairs being forced into less than ideal territories for a particular season. Competition occurs within the species as Horned Grebes fight amongst each-other for the best nesting sites, and they also compete with other grebes, such as the Pied-billed. The two species of Grebe, (Horned and Pied-bill), have the same physiological constraints limiting the locations that can be utilized for nesting. They are both very territorial and exploit similar food resources, which is why they won’t coexist too closely during the breeding season .When intra-species competition occurs for territories, most often it is the Horned Grebe that ends up having to relocate (Osnas 2003).

Pre-Winter Molt Habitat

After the mating season the exciting plumage of the spring and summer is no longer necessary for the Horned Grebe, and at this time a molt occurs. The winter molt and replacement in Grebes can last from anywhere from17-35 days (most often around 20). During this period they will replace all flight feathers simultaneously and this can severely affect their mobility (flight), and ability to evade predators. During this wing molt and regrowth period the Grebe will find a larger body of water to temporarily different from where the breeding grounds where located; it may still be within the breeding or winter range, but it is an alternate habitat. This habitat is separate from that of the breeding and wintering grounds and is important for their survival, since molting so many flight feathers leaves them temporarily unable to fly (Stout & Cook 2002).

Winter Habitat

Horned Grebes prefer to winter on deep open water unlike the territories used during the mating seasons. Primarily their choice is to winter in the ocean or bays but they will also inhabit large lakes (Sibley 2003). Near-shore, ice-free, sheltered waters such as those found in Puget Sound are perfect winter habitats because of the rich resources found here (Holm & Burger 2002).

During periods of foraging, the Horned Grebe will be on the surface of the water one second and then shoot beneath the surface and disappear with barely a ripple in the water the next. After a period of submersion of anywhere from 10-30 seconds the bird will appear in some other location, sometimes quite far from where it originally disappeared, often paddling around the same area for a bit longer before diving under again to hunt. The grebes have been observed partaking in these foraging sessions alone, in pairs, or even in a group of three on one occasion. After each foraging session they would immediately begin to preen themselves for periods of time afterward (Pers. Obs.).

Since the Horned Grebes swallow their food whole, some of the things they are ingesting are not completely digestible. As a result of this, the Grebe is known to at times ‘cough up’ pellets. The pellets that are regurgitated are small, ovular clumps that have been found to be a mixture of things the bird was possibly unable to digest: hairs, feathers, animal bones etc (Storer 1969).

Horned Grebes eating their feathers has been observed by many but is understood by few. It seems to play such an important role in the life of Grebes that parents will even feed feathers to their young chicks. Upon inspection of the stomachs of Horned Grebes one section of their stomach is nearly always plugged with feathers; the Grebes with the larger feather plugs are found to have more remains of hard-bodies invertebrates and fishes inside them than birds with little to no feather plugs in their stomachs. These findings have lead to the belief that feathers are ingested as a way to prevent bones and chitin from entering the intestinal tract, which could possibly cause a puncture (Storer 1969).

The advertising call is a one syllable vocalization. It is believed to be the first step in pair formations and is then later used as a contact call and as a warning. It is a single note with a nasally sound, descending in pitch and then rattling in the end: aaanrrh (Storer 1969; Stedman 2000).

Trilling vocalizations have a number of purposes and variations, and are used in duets of triumph after a mated pair chases off a territory usurper or after successful copulation (Storer 1969; Stedman 2000).

The softer ga ga sounding calls vary in loudness and are heard during nest building, as alarm calls, and sometimes pre-dive (Storer 1969: Stedman 2000).

During the Horned Grebe’s stay on the Evergreen Campus I found that they are a very quiet bird. They made no vocalizations on any day of my observations, at least none that are audible from shore. I never observed them fly and therefore never heard the sound of wing-beats or the sound of their feet slapping the surface of the water as they try and get airborne. Even when diving to foraging, they don’t make a splash that is audible from shore (Pers. Obs.). Due to this quiet nature of the migrant Horned Grebes at Evergreen I do not have an example of any of their vocalizations.

Locomotion

Terrestrial: Grebes have lobed feet and legs that are set far back on their bodies. This makes walking on land quiet awkward and slow, which is why majority of their time is spent on the water (Proctor & Lynch 1993; Stedman 2000). No matter the time of day, or the weather situation while I observed the Horned Grebes on the Evergreen campus I never once saw them on shore (Pers. Obs.).

Flight: Flight is a tool used often in the mating grounds of Horned Grebes for a number of different circumstances: approaching a mate after being separated for a period of time, when attacking another bird (generally intruders on their territory), flying from one habitat to another in the evening, and upwind flight (Storer 1969). Migration flight occurs at night with an average flight speed of 34 mph recorded during migration with no tail wind present (Binford & Youngman 2010).

Swimming and Diving: When swimming on the surface they will alternate strokes of the

feet, treading water, when swimming underwater simultaneous foot strokes are used for faster propulsion (Storer 1969). Wings are generally not used underwater to assist with swimming, but they may change the position of the wings to make turns etc. Underwater swimming speed averages around 3.28ft/sec (Stedman 2000). Prior to diving underwater to forage, the feathers of the body will be slicked down by contracting the abdominal muscles, reducing friction an allowing for more speed under the surface (Sibley 2003; Stedman 2000; Storer 1969).

There does not appear to be any pattern or method behind the diving. At times a pair or a group will seem to all dive simultaneously to forage for a bit, but on other occasions one bird will forage away from the others to be followed later. Length in time spent under the surface varied quite a bit from a quick 10 second dive to almost an entire minute going by before I’d see one come up for air (Pers. Obs.).

Self Maintenance

Preening: Taking care of the feathers is an essential part of bird life and behavior because the feathers themselves do not have any kind of internal maintenance system. After a while without care they would age and become brittle and damaged from the elements. The preen gland is located in the rump and secretes an oil which the birds apply to their feathers with their bill to clean and preserve them. Grebes have some of the largest preen glands of any bird. The more oil they apply, the dryer their feathers will stay while on the water and the warmer they will stay (Gill 2007). Immediately after diving and foraging activities, preening takes place (Pers. Obs.).

Resting: When the Horned Grebe isn’t foraging or preening it seems to be resting on top of the water not actively swimming but lightly treading water (Pers. Obs.). Typically when resting or sleeping the Horned Grebe will take on the pork-pie position when one foot is tucked up under the wing and the neck turned around so the head can rest on the back (Stedman 2000; Storer 1969).

Stretching: After preening for a bit, the grebes will open their wings to ‘stretch’ and flap their feathers for a couple seconds (Pers. Obs.).

Agonistic Behavior

During the mating season Horned Grebes become extremely territorial and defensive and fighting is common. Threatening birds will swim quickly towards a rival, sometimes half flying in an attempt to chase away the rival. If the threatened male doesn’t back down, fighting will occur. This results in breast to breast combat, wings open wide with each trying to get at the others neck. To stop the fight one of the males will often dive underwater, but the other will follow suit to continue the fight below the surface (Stedman 2000; Storer 1969).

On wintering grounds no fighting is recorded between grebes or amongst the small flocks of other water fowl. They seem to avoid conflict, swimming away when some of the other species come to close (Pers. Obs).

Sexual Behavior

Displays:Grebes are known to have some of the most elaborate courtship displays of any birds. Displays are used for many different aspects throughout the breeding season: pair formation, selection of nest sites, establishing territories, copulation, incubation, and chick-rearing (Sibley 2001). One example of these elaborate displays is the famous weed dance that occurs after the initial discovery of a possible mate is made. During this display mutual diving occurs and the two birds surface with some type of water vegetation clasped in their bills. They then come together breast to breast with head feathers standing on end for the ‘dance’. Immediately following the dance they turn parallel to one another and move quickly together across the water’s surface. The weed dance is repeated a few times and then the pair bond is formed (Konter 2001; Stedman 2000).

Nesting: With the lack of mobility, nesting sites are never more than 3 meters away from the main water habitat. The nests are constructed by both the male and female and can take as little as 3 hours or up to a couple of days. There are four different nest types constructed by Horned Grebes: nests connected to the stalks of floating vegetation (floating nest), built in shallow water from the bottom up so as to be affixed, built on top of a rock within the water, and onshore nests near the edge of the water. They are opportunistic when choosing nesting material, but in past studies no pattern has been found for which type of nest is built for the particular season (Sibley 2001;Storer 1969).

Parenting: Eggs are laid on alternate days with incubation starting with the laying of the first egg and lasting 24 day. Average clutch size is between 3-7 eggs, but most often 4 eggs weighing 20 grams. Nest failure is common amongst Horned Grebes. At some breeding locations only half of the breeding pairs actually hatch chicks. Common causes of nest failure are predation, wave damage, flooding of nests, and desertion of parents. The average brood size at fledging is 1.2, with most chick mortality generally occurring within the first 3 weeks and is most often due to starvation (Konter 2001; Summers, Mavor & Hancock 2009). Chicks are precocial: when hatched they are covered with dense, very short, straight down and their feet are lobed and partially webbed exactly like the adults. When newly hatched, the chicks can swim and dive as needed but do not spend much time in the water because the down is not the best insulation. Most of the early weeks are spent on one of the parents backs huddled under the feathers with the other parent bringing back food. By 1-2 weeks the parents will have each chosen a favorite chick which they give feeding priority and allow to dominate the other chicks. After the carrying and feeding phase the pair of parents will usually part ways (Fjeldsa 1977).

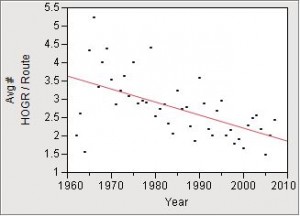

In North America the estimated population of Horned Grebes is >100,000 individuals however, in the last 100 years considerable declines in abundance have been noted (Anderson, Bower, Nysewander, Evenson & Lavorn 2009; O’donnel & Fjeldsa 1997; Sauer 2011). Although studies are showing a declining trend throughout nearly the entire range of the Horned Grebe, they are still considered low risk and of low priority from a conservation standpoint in the United States (O’donnel & Fjeldsa 1997). The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) lists their western population status as “special concern”, meaning they are in danger of becoming threatened or endangered. This is of interest because the population in Western Canada comprises 92% of the breeding range for North American Horned Grebe (COSEWIC, 2014). Below are some population trend estimates showing Horned Grebe decline from North American Breeding Bird Survey data.

Avg # HOGR / Route BBS Entire 1962-2012

Fig. 3 The number of Horned Grebe sighted during Breeding Bird Surveys over the entire range has been in decline over the past 50 years. A p value of >0.0001 shows statistical significance. Data from BBS https://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/

Horned Grebes are habitat specialists. They are perfectly adapted for life on the water but due to their lack of mobility on land and other habitat specific life history traits this makes adapting to environmental changes very difficult (O’donnel & Fjeldsa 1997). Loss and alteration of key habitats is the number one cause for concern for conservationists. Most of the habitat changes affecting the Horned Grebes are from anthropogenic sources: sequestering of wetlands for agricultural uses, changes in the water level, pollution and water contamination, introduced species, increase in use of water habitats for recreational purposes, impacts of fisheries, and any other way that human interaction interferes with natural physical processes (Andersen et al. 2009; Bouffard & Hanson 1997; O’donnel & Fjeldsa 1997; Summers et al. 2009). The preservation of existing wetlands and construction of new wetland habitat is key to stabilizing Horned Grebe and other waterfowl populations. Studies done on “borrow pits”, >3 ha ponds created when extracting soil for road building, have shown them to provide productive habitat for many waterfowl, including Horned Grebe (Kuczinski and Pazkowski 2012). Borrow pits surveyed at Peace Parkland in Alberta, Canada were actually more productive in grebe numbers and chick production than natural wetlands in the same area (Kuczinski et. al. 2012). The preference of Horned Grebe to small ponds for breeding makes construction of new habitat a viable conservation option when natural habitat has been destroyed or degraded.

Anderson, E. M., Bower, J. L., Nysewander, D. R., Evenson, J. R. and Lovvorn, J. R. 2009. Changes in Avifaunal Abundance in a Heavily Used Wintering and Migration Site in Puget Sound, Washington, During 1966-2007. Marine Ornithology 37: 19-27

Arnold, T. W. 1989. Variation in Size and Composition of Horned and Pied-billed Grebe Eggs. The Condor 91: 987-989. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1368085

Binford, L. C. and Youngman, J. A. 2010. Flight Speed of Migrating Red-necked and Horned Grebes. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 122: 374-378. http://dx.doi.org/10.1676/08-060.1

Bouffard, S. H., & Hanson, M.A. (1997). Fish in Waterfowl Marshes: Waterfowl Managers’ Perspective. Wildlife Society Bulletin 25: 146-157. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3783297

Council on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2014. http://www.cosewic.gc.ca/

Fjeldsa, J. 1973. Distribution and Geographical Variation of the Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus (Linnaeus, 1758). Ornis Scandinavica 4: 55-86. http://jstor.org/stable/3676290

Fjeldsa, J. 1977. Guide to the Young of European Precocial Birds. Tisvildeleje, Denmark: Skarv Nature Publications.

Fraabord, J.1976. Habitat Selection and Territorial Behavior of the Small Grebes of North Dakota. The Wilson Bulletin 88: 390-399. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4160778

Gill, F. B. 2007. Ornithology. (3rd ed.) New York, NY: W. H. Freeman and Company

Hammer, K. M. 2012. Personal field observations made for Ornithology class at The Evergreen State College. Faculty: Alison Styring & Dina Roberts. 09 October 2012-26 November 2012.

Holm, K. J. and Burger, A. E. 2002. Foraging Behavior and Resource Partitioning by Diving Birds During Winter in Areas of Strong Tidal Currents. Waterbirds 25: 312-325. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1921973

Konter, A. 2001. Grebes of Our World. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions.

O’Donnel, C. and Fjeldsa, J. 1997. Grebes- Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Grebe Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. Vii + 59 pp.

Osnos, E. E. 2003.The Role of Competition and Local Habitat Conditions for Determining Occupancy Patterns in Grebes. Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology 26: 209-216. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1522554

Proctor, N. S. and Lynch, P. J. 1993. Manual of Ornithology Avian Structure and Function. Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Brothers Inc.

Sauer, J. R., J. E. Hines, J. E. Fallon, K. L. Pardieck, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W. A. Link. 2011. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2010. Version 12.07.2011 USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD

Sibley, D. A. 2003. The Sibley Guide to Birds of Western North America. New York, NY.:Alfred A Knopf Inc.

Sibley, D.A. 2001. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf Inc.

Speich, S. M., Manuwal, D. A. and Wahl, T. R. 1991. In my Experience: The Bird/Habitat Oil Index: A Habitat Vulnerability Index Based on Avian Utilization. Wildlife Society Bulletin 19: 216-221. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3782334

Stedman, S. J. 2000. Horned Grebe Grebe (Podiceps auritus), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online http://0-bna.birds.cornell.edu.cals.evergreen.edu/bna/species/505doi:10.2173/bna.505

Stout, B. E. and Cook, F. 2003.Timing and Location of Wing Molt in Horned, Red-Necked and Western Grebes in North American. Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology 26: 88-93 http://0-www.jstor.org.cals.evergreen.edu/stable/1522471

Storer, R. W. 1969. Behavior of the Horned Grebe in Spring. The Condor 71: 180-205. Article DOI: 10.2307/1366078

Summers, R. W., Mavor, R. A. and Hancock, M. H. 2009. Correlates of Breeding Success of Horned Grebes in Scotland. The Waterbird Society 32: 265-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1675/063.032.0206

Leave a Reply