By tgreyfox [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Family: Passeridae

Genus: Passer

Species: Passer domesticus

Introduction

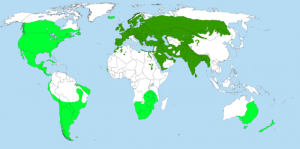

The House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) is an Old World sparrow that was introduced to North America and took rapidly to the continent becoming known as somewhat of a pest.

Although also called sparrows, Old World Sparrows belong to a different family than our native sparrows (family Emberizidae). They are seemingly similar to emberizid sparrows but are larger and chunkier with stouter bills and short legs and tails. Their markings consist of a rufous back and wings with black streaking and a broad white wing bar, males have a gray crown with a rufous nape and supercilium or eyebrow. They have white cheeks and a distinctive black bib. Females have a gray-brown crown and postocular line, a pale buff supercilium, a black throat and unmarked breast.

Widely distributed across most all of North America, excluding Alaska and northern latitudes of Canada, House Sparrows are abundant in human inhabited areas.They are permanent residents throughout North America and do not migrate.

By User:Cactus26 [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

On the Evergreen Campus I have seen them at the Organic Farm looking for forgotten seeds in the beds, foraging in the gravel driveway and perched in bushes and along the fences. I also saw them occasionally looking for crumbs on the bricks by Police Services and at the feeders by the side of the Sem I building.

House Sparrows inhabit human-developed areas from cities and towns to rural agricultural farms (Sibley, 2001). They have co-existed with humans for so long that they are not found in areas that are not populated by humans. They avoid extensive woodlands, grasslands and deserts and are not seen in areas that are not cultivated. When driving through the desert House sparrows will be seen in most small roadside towns but not in the space between them. They are non migratory so there habitat stays the same throughout the year. The House Sparrow is a very sedentary species so once they develop a nest site they will spend the majority of their lives in close proximity to it (Lowther and Cink, 2006).

By Ernst Vikne [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The House Sparrow can be easily distinguished from other Passerines by their simple song, a monotonous series of chirps lacking in rhythm or beginning and end. Their call is a husky fillip or a low rattling series while their flight call consists of a soft husky pido and a descending piirv (Sibley, 2003). Females cheep little except when they have lost their mates and want to attract new ones (Lowther and Cink, 2006).

They inherit their songs rather than having to learn them so even when raised in isolation they are still able to develop a perfect song.

Observation

Their usual mode of terrestrial locomotion is hopping. When detecting a threat they flit their tail up and down numerous times. They preen often while they are perching. When trying to assert dominance over one another males will hop at each other with their chests kind of puffed out. Often observed in small flocks.

House Sparrows, being non migratory birds, have to be able to endure more extreme temperature changes from season to season. To cope with this they enhance their insulation during cold seasons by molting into fresh, thick plumage, thus increasing their plumage weight 70 percent, from 0.9 grams of plumage per bird in August to 1.5 grams of fresh plumage in September (Gill, 2007).

House sparrows participate in something called conspecific brood parasitism, meaning that females of the same species will occasionally lay their eggs in another females nest for her to take care of. This has lead to the ability of females to recognize parasitic eggs (eggs that do not belong to them) in their nest. Results from a study conducted on captive birds showed that egg rejection is not affected by relative egg size or overall color, but changes in the spot pattern on the eggs resulted in significantly higher rates of rejection from the nest. Therefore suggesting that brood parasitism may, over time, be favoring the maintenance of spotted eggs (López et al, 2010).

House sparrows will nest in any sheltered cavity from birdhouses to nooks in crevices in buildings or build closed nests among tree branches (Sibly, 2003). They will also forcibly evict previously established cavity nesters from their nest and take it over. They are usually monogamous, with a low rate of extra-pair copulations (López et al, 2010). Both the male and female will work to protect their territory that surrounds their nest site. The male will also defend his paternity opportunities against other males that are showing interest in his mate. They use two alternative strategies, frequent copulation to increase the chances of paternity of the offspring, and mate-guarding in which he guards his mate as if she is part of his territory. Male House Sparrows will adjust their strategies based on the breeding density. They will also modify their strategy according to their individual abilities: mate-guarding intensity was shown to positively correlate with the black breast badge size (Hoi et al, 2011).

First-year survival of young is 20%; annual survival for adults 45-65%.

North American population grew from 50 pairs in 1853 to an estimated 150,000,000 birds in 1943. The population has been declining since 1966.

Due to the monoculture crops of modern industrial agricultural practices paired with heavy use of chemical pesticides, the population of the ever so abundant House Sparrow is actually in decline. The population has been declining since 1966. Despite the decreasing populations, the species is still one of the most common birds on the continent (Sibly, behavior). Because it is an introduced species the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, as well as U.S. and Canadian federal, state and provincial regulations exclude them from protection.

Competition for nest sites can be reduced by placing nest boxes intended for other species at a great distant from areas populated by House Sparrows (Lowther and Cink, 2006).

By Wilhelm von Wright (1810–1887) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Anon. House Sparrow. Seattle Audubon Society; Retrieved from BirdWeb: http://www.birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/house_sparrow Gill, Frank B. 2007. Ornithology. Third Edition. W. H. Freeman and Company. New York Hoi, H, Tost, H, & Griggio, M 2011, ‘The effect of breeding density and male quality on paternity-assurance behaviours in the house sparrow, Passer domesticus’, Journal Of Ethology, 29, 1, pp. 31-38, Wildlife & Ecology Studies Worldwide, EBSCOhost, viewed 15 November 2012. López-de-Hierro, M. Dolores G., and Gregorio Moreno-Rueda. “Egg-Spot Pattern Rather Than Egg Colour Affects Conspecific Egg Rejection In The House Sparrow ( Passer Domesticus).” Behavioral Ecology & Sociobiology 64.3 (2010): 317-324. Wildlife & Ecology Studies Worldwide. Web. 30 Nov. 2012. Lowther, Peter E. and Calvin L. Cink. 2006. House Sparrow (Passer domesticus), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://0-bna.birds.cornell.edu.cals.evergreen.edu/bna/species/012doi:10.2173/bna.12 Sibley, D.A. 2001. The Sibley Guide To Bird Life and Behavior. Alfred A. Knopf. New York. Sibley, D.A. 2003. The Sibley Guide To Birds of Western North America. Alfred A. Knopf. New York. Tomás Pérez-Contreras, et al. “House Sparrows Selectively Eject Parasitic Conspecific Eggs And Incur Very Low Rejection Costs.” Behavioral Ecology & Sociobiology 65.10 (2011): 1997-2005. Wildlife & Ecology Studies Worldwide. Web. 15 Nov. 2012.

Leave a Reply