Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Charadriidae

Genus: Charadrius

Species: Charadrius vociferus

Introduction

By ShutterGlow.com [CC-BY-2.5], via Wikimedia Commons

Another interesting feature is their colored eye rings, which are red. These eye rings are common in other shorebirds and in the family Charadriidae, in general (Sibley 2003). It’s hypothesized that this may help conceal their eye sockets (Graul 1973). In fact, most if not all of the black to white or gray to white markings of various plovers, are thought to provide protection and overall camouflage in its environment. These contrasting feather colors function as a “disruptive coloration”, which deters predation. This coloration is particularly useful during nesting season (Graul 1973). During mating season, male Killdeer’s double breast bands seem to enlarge, by holding an upright posture he may stretch and fluff up his plumage, reinforcing certain aggression displays (Mundahl 1982,Huxley 1958). Through different activities Killdeer may use their plumage accordingly.

Killdeer range all over the continental U.S., and are found as residents in Canada, Mexico, and the Western Caribbean (Sibley 2003). There are residential, transient and migratory killdeer all across these territories (Sanzenbacher 2002). Breeding range extends from Mexico all the way up the Lower Arctic Circle and throughout most of the United States, while the winter range includes British Columbia to Ontario and again most of the United States and South as far as the West Indies (Bent 1929).

The northern populations, such as those of the Evergreen campus, migrate; southern populations do not (Jackson 2000). It’s a known fact that climate highly influences migratory behaviors. If temperatures plummet to below 0°C., many if not all Killdeer will migrate (Chung 2001). Likewise, studies have shown that habitat needs and space use requirements are also significant factors influencing the migration of both wintering and year-round resident Killdeer (Sanzenbacher 2002).

Killdeer thrive in a wide variety of environments. Despite being considered a “shorebird”, the Killdeer inhabitate both coastal and inland areas (Sibley 2003). They can be found habitually in mudflats, short-grass meadows, and gravel bars; likewise, they are also commonly found in modern human landscapes, including pastures, golf courses, road shoulders, ball fields, mall parking lots, and construction sites (Francl 2002). It is not uncommon for a person to be pulling out of a gravel driveway only to find killdeer eggs nestled there!

Factors that play a role in choice of habitat for Killdeer include, food and water resources (i.e. the presence of short vegetation and standing water), predation pressures, presence of other animals that help reduce fatalities, and human influence (Taft 2004, 2005, Long 2001).

They can also be found in desert surrounding Great Basin wetlands (Sibley 2003). Killdeer are often one of the first birds to appear in newly planted restored tallgrass prairie habitat, along with other species such as horned larks and red-winged blackbirds (Olenchowski 2009). They thrive there for the first two years that the area is out of crop rotation, but as grass grows taller, the killdeer and other species are gradually replaced by such prairie specialists as the Henslow’s sparrow (Ammodramus henslowii) and the bobolink (Dolichonyx oryzivorus) (Olenchowski 2009 and Farmer 2006)

They also inhabit agricultural fields of low-tillage dryland crops, such as corn, soy, and wheat, but they don’t disturb the crops themselves (Sterner 2002). Killdeer, along with horned larks and other species that thrive in existing agricultural fields, exhibit a decline after the conversion, but then there is an increase in other, more threatened species such as dickcissel (Spiza americana) and grasshopper sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum) (Murray 2002).

Just as varied as is the environment in which Killdeer dwell, so is the food they eat (Smith 2012). They are carnivorous, eating mostly aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates, including grasshoppers, beetles, worms, and sod webworms (Taft 2004). Although, plant material is present, it is rarely part of their diet (Colwell 2010).

Killdeer will commonly forage for earthworms and other invertebrates in areas that use farming practices that expose soil (Taft 2005). This may be a reason why we commonly see Killdeer forage away from the water.

One unique feeding behavior Killdeer has developed is called the “foot stir” technique (Smith 1970). When the bird stands on one foot it vibrates the other in the water quickly, so as to stir and stimulate movement from prey. After about five to ten seconds, it will pause and sharply peck at the water. The feeding strategy is as follows: running, a few steps to a few yards, periodically stopping with head held high to scan for movement, then an abrupt peck (Chung 2001).

Like many other birds, Killdeer use complex vocal sequences to relate important information to neighboring birds. This information can be attributed to: resources, mate attraction, territorial advertisement, and predation/danger. Many if not all displays provide these characteristics (Sung 2005). Killdeer have vocal and non-vocal sounds that range from soft, short-range calls like those between adults and young, to loud nuptial aerial song that can carry for miles (Miller 1984). I noticed that most of the time you would hear Killdeer before seeing them (Masi pers.obs.) They are said to have “higher fundamental frequencies” than many other plovers (Sung 2005). This may explain why it is more common to hear them than witness behavior.

Displays are certain changes in Killdeer behavior which, depending on the type of activity the bird is engaged in, will show noticeable differences in vocal or wing patterns. During flight displays, they are known to alter their song vocalizations especially towards the very end of the display (Miller 1996). There are both vocal and wing variations in distraction displays. Compared to other plovers who also do the broken-wing distraction display, it was noticed that Killdeer have a more complex vocal display that vary in duration, are more complicated than the other displays, harsh-sounding, and repeated at the end (Sung 2005). Furthermore, during breeding displays, Killdeer exaggerate wing-beats with a lateral rocking motion (Miller 1996).

“K’dee…k’dee…k’dee-dee-dee” or “deet-deet-deet-deet”. Alarm calls. (Recorded on the Evergreen soccer field, 11/8/12)

Long stuttering trill, heard during courtship display, aggressive encounters, or as an alarm call. (Recorded on the Evergreen soccer field, 11/8/12)

Two Killdeer foraging and commencing near the shore during low-tide. (Recorded by Caroline Masi at Priest Point Park, Olympia, WA 11/19/2014)

Below a Killdeer flying by to catch up with the flock. (Recorded by Caroline Masi at William Cannon Trail, Olympia WA 11/22/2014)

Above, Killdeer calling an infrequent, uncertain, low “keeeee” call. (Recorded by Caroline Masi at William Cannon Trail, Olympia Wa 12/1/2014)

Killdeer are usually found in medium to large flocks, always performing their running-stopping-bobbing gait (Hancock 2010). The head-bobbing movement is considered to enhance vision for visual foragers (Hancock 2010). This conspicuous movement is only one thing that distinguishes Killdeer from other plovers.

In breeding season, flocks can be as many as 1,000 birds in some areas (Sanzenbacher 2002)! Killdeers are seasonally monogamous, and maintain individual breeding territories. They have been known to retain the same mate and the same nesting site for multiple breeding seasons (Lenington 1975). They nest almost anywhere on the ground, including gravel bars in streams, dune hollows on sandy beaches, tussocks on open tundra (Sibley 2003). They prefer habitats with short, sparse vegetation, including cornfields in the midwest (Best 2001).

Throughout the United States, Killdeer nesting and breeding begins in early spring, dependent on location (Chung 2001). Clutch size is usually two to four eggs, but four is the most common, with an incubation period of 22-28 days (Chung 2001). Males and females invest equally in territorial establishment and defense during pre-nesting and egg-laying period, and in nest building and incubation (Mudahl 1982). Males do, however, defend both eggs and chicks more intensely than females from human and animal predation (Brunton 1990).

An essential defense mechanism that Killdeer perform is the distinctive “broken-wing” display (Jackson 2000). This technique relies on deception and good acting to divert predators away from the nest or young. Adult killdeer will flop around, acting like they are injured, leading the predator away. Once the predator is far away, the adult suddenly “heals” from its injury and flies off. This technique works almost every time (Fisher 1996, Brunton 1990)!

By Audrey from Central Pennsylvania, USA (Mother Killdeer) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Andres, B.A., Smith, P.A., Morrison, R.I.G., Gratto-Trevor, C.L., Brown, S.C. & Friis, C.A. 2012. Population estimates of North American shorebirds. Wader Study Group Bull Vol. 119 Issue 3: 178–194.

Best, L.B. 2001. Temporal Patterns of Bird Abundance in Cornfield Edges During the Breeding Seasons. The American Midland Naturalist 146:94-104.

Brunton, D.H. 1990. The effects of nesting stage, sex, and type of predator on parental defense by killdeer (Charadrius vociferous): testing models of avian parental defense. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 26: 181-190

Boyle, A.W. 2006. Why do birds Migrate? The role of food, habitat, predation and competition. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona.

Burlock, B. Field notes taken for an Ornithology class at The Evergreen State College, Ornithology Field Journal, 10/2/2012 – 12/10/2012, The Evergreen State College.,

Colwell, M.A. 2010. Shorebird Ecology, Conservation and Management. University of California Press.

Chung, H. 2001. “Charadrius vociferus”. Animal Diversity Web Retrieved from http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Charadrius_vociferus/

Farmer, A. and Durbian, F. 2006. Estimating Shorebird Numbers at Migration Stopover Sites. The Condor Vol.108 No.4: 792-807.

Fisher, C.C. 1996. Birds of Seattle and Puget Sound. Lone Pine Publishing, Canada

Francl, K.E. and Schnell, G.D. 2002. Relationships of human disturbance, bird communities along the land-water interface of a large reservoir. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Vol. 73 Issue 1: 67-93

Graul W.D. 1973. Possible Functions of Head and Breast Markings in Charadriinae. The Wilson Bulletin Vol. 85, Issue 1: 60-70

Hancock, J.A. 2010. The mechanics of terrestrial locomotive and the function and evolutionary history of head-bobbing birds. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Ohio.

Haig, S.M., and Oring, L.W. 1998. Wetland connectivity and waterbird conservation in the Western Great Basin of the U.S. Wader Study Group Bulletin. Vol. 85 : 19-28

Huxley, J.S. 1958. Why two breast-band on the Killdeer? The Auk Vol. 75 Issue 1 : 98-99

Jackson, B.J. and J.A. Jackson. 2000. Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://0-bna.birds.cornell.edu.cals.evergreen.edu/bna/species/517 doi:10.2173/bna.517

Lenington, S. and Mace, T. 1975. Mate Fidelity and Nesting Sites Tenacity in the Killdeer. The Auk Vol. 92 Issue 1: 149-151

Long, L. L. and Ralph, C. J. 2001. Dynamics of habitat use by shorebirds in Estuarine and agricultural habitats in north western California. The Wilson Bulletin Vol. 113, Issue 1: 41-52

Masi, C.E. Field notes taken for an Ornithology class at The Evergreen State College, Ornithology Field Journal, 11/1/2014 – 12/10/2014, The Evergreen State College.,

Miller, E.H. 1984. Communication in breeding shorebirds. Pages 164-241 in Shorebirds: Breeding Behavior and Populations. (Burger, J. and Olla, B.L.) Plenum Press, New York.

Miller, E.H. 1996. Acoustic Differentiation and speciation in shorebirds. Pages 241-56 in Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds. Cornstock/Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

Mineau, P., Downes, C.M., Kirk, D.A., Kayne, E., and Csizy, M. 2005. Patterns of bird species abundance in relation to granular insecticide use in the Canadian prairies. EcoScience Vol. 12 Issue 2: 267-278

Mundahl, J.T. 1982. Role Specialization in the Parental and Territorial Behavior of the Killdeer Charadrius-Vociferus. Wilson Bulletin Vol. 94 No.4: 515-530.

Murray, L.D., Best, L.B., Jacobsen, T.J., et al. 2002. Potential effects on grassland birds of converting marginal cropland to switchgrass biomass production. Biomass and Bioenergy 25: 167-175.

Olechnowski, B.F.M., Debinski, D.M., Drobney, P., et al. 2009. Changes in Vegetation Structure through Time in a Restored Tallgrass Prairie Ecosystem and Implications for Avian Diversity and Community Composition. Ecological Restoration Vol.27 No.4: 449-457.

Sanzenbacher, P. M. and Haig S. M. 2002. Regional Fidelity and Movement Patterns of Wintering Killdeer in an Agricultural Landscape. The Waterbird Society Vol. 25, Issue 1: 16-25

Sibley, D. A. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. 1st ed. Andrew Steward Publishing, New York, NY.

Smith, S. M. 1970. Feeding Behavior by a Killdeer. The Condor Vol. 72, Issue 2: 245

Smith, R.V., Stafford, J.D., et al. 2012. Foraging Ecology of Fall-Migrating Shorebirds in the Illinois River Valley. PLOS ONE Vol. 7 Issue 9.

Sterner, R.T., Petersen, B.E., Gaddis, S.E., et al. 2002. Impacts of small mammals and birds on low-tillage, dryland crops. Crop Protection 22: 595-602.

Sung, H.C., and Miller, E.H. 2005. Breeding vocalizations of the Piping Plover: structure, diversity, and repertoire organization. Canadian Journal of Zoology Vol. 83 Issue 4

Taft, O.W. and Haig, S.M. 2006. Landscape context mediates influence of local food abundance on wetland use by wintering shorebirds in an agricultural valley. Biological Conservation Vol. 128 Issue 3: 298-307

Taft, O.W. and Haig, S.M. 2005. The value of agricultural wetlands as invertebrate resources for wintering shorebirds. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment Vol. 110 Issues 3-4: 249-256

Vogt, A. 2014. State of the Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology

This section includes observations I made of Killdeer around the Budd and Eld Inlet in Olympia, WA between November – December 2014. My method of observation was to watch individual Killdeer until an action occurred (usually 5-10 seconds), then would move on to another bird in the flock, I would rotate this cycle until every bird had flown away.

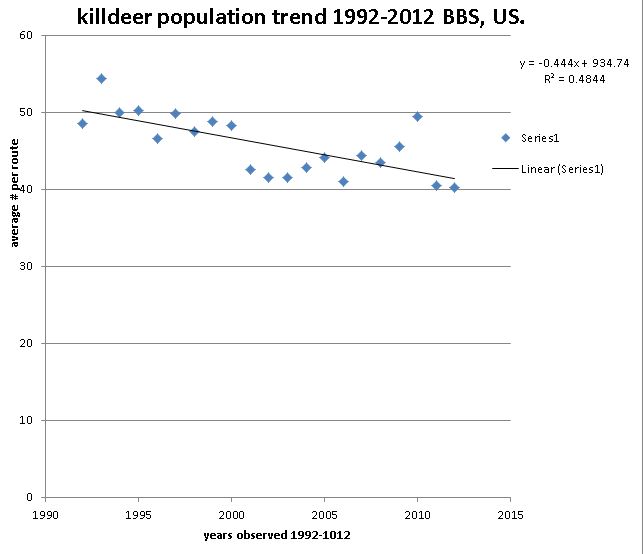

Population Trends

With a trend line R value of .4844 from the BBS, the data seems to show a population drop of Killdeer across the US, from 1992-2012.

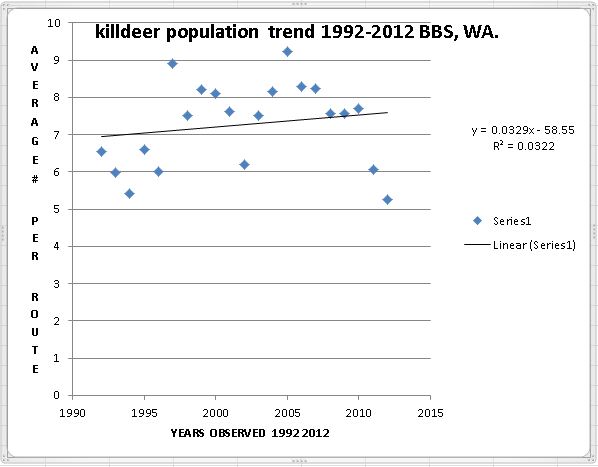

With a trend line R value of .0322, from the BBS, the trend line might seem that there is a slight rise in Killdeer population in WA State, from 1992-2012 but the data points are actually quite all over the place, and is not a strong trend line.

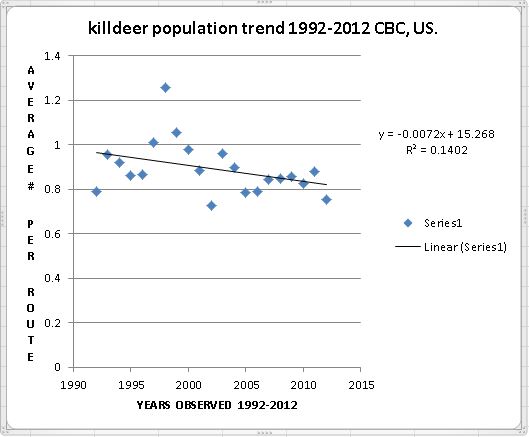

With a trend line R value from the CBC from 1992-2012 of .1402, again shows there is a drop in Killdeer population in the US, but is not a strong trend line.

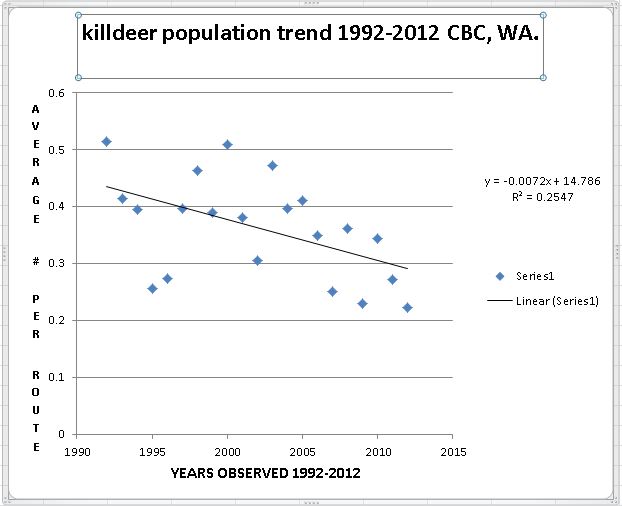

With a Trend line from the CBC in WA State again from 1992-2012, showing a drop in Killdeer population with a somewhat stronger Trend line of .2547, makes me believe that the trend line from the BBS in WA, is not reliable, and that there is at least somewhat of a drop in Killdeer population in the wintering population of Killdeer in WA State, from 1992-2012.

The breeding Bird Survey was designed to monitor the status of North American breeding birds; however 32 of the 50 North American shorebird species (64%) breed in northern regions of the continent not covered by the survey (Robbins 1986) . The Killdeer is one of the most widely distributed shorebird species in North America (Sanzenbacher 2001).

Since the killdeer seems to be abundant and common, this as led to a general lack of concern regarding potential population declines (Haig, Sanzenbacher 2001). Examination of Killdeer population trends has never progressed beyond a general recognition of increases and declines in North America (Haig, Sanzenbacher 2001).

THREATS

When Killdeer are in agricultural areas, roadsides, and other altered areas, they can be exposed to higher levels of disturbance including nest destruction and predation along with harmful toxins (Sanzenbacher 2002). A closer look into agricultural areas in Canada, specifically into insecticide usage, have determined that these chemicals are in fact lethal, and can have serious negative side effects on Killdeer and other such birds as the robin, horned lark, house sparrow and mourning dove (Mineau 2005).

The most prominent factor implicated in Killdeer declines has been the widespread loss and alteration of wetland and upland habitats of North America (Haig 1998, Vogt 2014). Humans have degraded wetland habitats through development of port facilities, pollution, over harvesting of bait and shellfish, and other activities; this disrupts Killdeer population sustainability (Colwell 2010).

Along with the Killdeer, other shorebirds that share the same habitat have suffered from wetland disturbance and habitat change. (Andres 2012, Vogt 2014) As a whole we can see a decline in the numbers of Mountain Plover, Piping Plover and Snowy Plover. Since these birds occupy threatened habitats, management and conservation of wetlands are imperative for population growth or sustainability. (Colwell 2010)

Human disturbance in the form of agriculture, industry, and urbanization can greatly influence the structure and development of bird communities. However, because Killdeer are attracted to, thrive and nest in human-modified environments and close to humans, their conservation status is of least concern (Francl 2002). It is estimated that there are at least 2 million Killdeer thriving in the U.S. and Canada (Andres 2012). Overall, there is a decline in population trends in the Killdeer across the US and survey wide.

Leave a Reply