Order: Columbiformes

Family: Columbidae

Genus: Zenaida

Species: Zenaida macroura

Introduction

The mourning dove is a bird most known for its somber call. However, with its wide range and its rank as the eleventh most abundant bird in its breeding range, the mourning dove’s outlook is anything but somber (Otis et al., 2008.) The mourning dove’s plumage is a pale gray-blue-brown with gray flight feathers, black spots on its wings, and one black spot beneath each eye. Males and females are easy to confuse by sight, though males tend to have a rosier tinge on their breasts. Both sexes have dainty black beaks suited for gathering seeds from the ground, pale red feet, and pale blue rings of skin around their eyes. Males weigh in at about 130g, while females tend to be a bit smaller at 123g (Poling and Hayslette, 2006.)

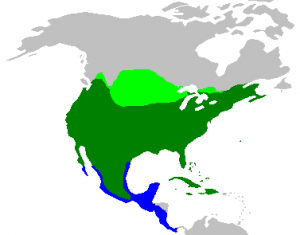

The mourning dove enjoys a large range across North and Central America. It has actually been called “one of the most widely distributed and popular game birds in North America” (Poling and Hayslette, 2006.) The mourning dove’s range spans from central Canada to as far south as Panama, wintering in Canada, living year-round mostly in the United States and Mexico, and summering in much of Central America. The doves breed in much of the range, and only the northernmost birds migrate south for the winter (Hernandez-Garcia and Mellink, 2018.) Of the doves that do migrate, some unlucky birds don’t make the journey and have been found to be important food sources for scavengers like coyotes in the deserts of the American Southwest (Rogers et al., 2014.)

As expected for a bird with such a wide range, the mourning dove can be found in a variety of habitats. However, the birds do have a preference for open habitats that often tend to be maintained by disturbance (Van Vuren, 2013.) This is due to their feeding habit of pecking seeds from the ground. Cropland in particular is attractive to mourning doves, as it holds a high concentration of food in one place (Collins et al., 2010.) The doves do like to have cover near, for roosting and nesting but they tend to avoid swamps and dense forests (Otis et al., 2008) (Collins et al., 2010) (Block and Morrison, 2010.) It’s important to note that while mourning doves prefer to nest in trees, they are very flexible and can nest on the ground, on man made structures, and in the southwest, on cacti (Otis et al., 2008.)

Mourning doves are granivorous birds that feed almost exclusively on the ground (Otis et al., 2008.) Due to their wide range mourning doves eat a wide variety of seeds and grains, though in captive studies they do seem to have a preference for white proso millet (Ploing and Hayslette, 2006.) These doves can be found at feedlots, picking up dropped grain from cattle (Meyers et al., 2006) as well as in agricultural fields, harvesting the seeds and grains there.

As mourning doves consume many seeds not all of them get digested and as a result, the doves can serve as important agents of seed spreading for plants. This can serve as an issue for farmers when the doves get ahold of noxious weed seeds. This happened in the case of the Benghal dayflower in Georgia, where the weed has spread out of control and in places where it thrives, mourning doves consume large amounts of the seeds and spread them (Goddard et al., 2009.)

Mourning doves are best known for their mournful coos often heard in the spring and summer. These coos are the advertising call from unpaired males to females during mating season (Otis et al., 2008.)

“Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura)” from xeno-canto by Thomas Beverly.

Breeding

Mourning doves tend to only live a year (Otis et al., 2008.) Making up for this shortened lifespan, mourning doves mate multiple times per season. If the weather is good, with average temperatures being around 53°F, hatching can begin mid February and continue through late September (Braun and Tomlinson, 2015) (Becker and Weisberg, 2015.) Mourning doves in the lower latitudes can nest up to five times in a season and lay two eggs per nest (Braun and Tomlinson, 2015) (Otis et al., 2008.) These birds also molt their feathers during breeding season, and the combined demands of producing and raising young and the growing of new feathers leads to lower body mass in the summer than in winter (Braun et al., 2015.)

Migration

Not all mourning doves migrate, but those living in the northernmost latitudes of their range (in southern Canada) do. When they migrate in the fall, those birds fly down into Central America, with many ending up in Mexico for the winter before heading back north in the spring (Hernandez-Garcia and Mellink, 2018.) As noted before, some of the doves don’t make the whole journey and in the Sonoran Desert, for example, scavengers (especially those who are injured) rely on fallen migratory birds for easy food (Rogers et al., 2014.)

Mourning doves aren’t a threatened species, being one of the most abundant bird species in North America (Otis et al., 2008.) They are also a very popular bird with hunters, with over 20 million killed by hunters annually for both subsistence and sport (Miller and Otis, 2010.) While mourning doves don’t appear to be in danger at this time, there are some concerns about hunters’ use of lead-containing ammunition causing unintended death in mourning doves and other animals in heavily-hunted areas. Lead shot has been banned in the hunting of waterfowl since 1991 in the US and 1999 in Canada, but it is still legal in many places for use against upland game birds such as mourning doves (Haig et al., 2014.) This is a problem because mourning doves feed on seeds on the ground and lead shot looks a lot like the seeds and grit that are important to a mourning dove’s diet. While the percentage of doves killed from lead ingestion are 0.2%-6.5% depending on location, these deaths are entirely preventable though the use of non-toxic shot (Schulz et al., 2007) (Plautz et al., 2011.) However, 84.8% of upland hunters opposed restrictions of lead shot in a 1999-2000 survey, so those advocating for lead shot bans have a ways to go (Schulz, 2007.)

Becker, M. E., & Weisberg, P. J. (2015). Synergistic effects of spring temperatures and land cover on nest survival of urban birds. The Condor, 117(1), 18-30. doi:10.1650/condor-14-1.1

Block, G., & Morrison, M. L. (2010). Large-scale effects on bird assemblages in desert grasslands. Western North American Naturalist, 70(1), 19-25. doi:10.3398/064.070.0103

Braun, C. E., Tomlinson, R. E., & Wann, G. T. (2015). Seasonal dynamics of mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) body mass and primary molt. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 127(4), 630-638. doi:10.1676/14-158.1

Braun, C. E., & Tomlinson, R. E. (2015). Timing of hatching in a mourning dove population in Tucson, Arizona. The Southwestern Naturalist, 60(1), 80-84. doi:10.1894/ekl-10.1

Collins, M. L., Small, M. F., Veech, J. A., Baccus, J. T., & Benn, S. J. (2010). Dove Habitat Association Based on Remotely Sensed Land Cover Types in South Texas. Journal of Wildlife Management, 74(7), 1568-1574. doi:10.2193/2009-465

Goddard, R. H., Webster, T. M., Carter, R., & Grey, T. L. (2009). Resistance of Benghal Dayflower (Commelina benghalensis) Seeds to Harsh Environments and the Implications for Dispersal by Mourning Doves (Zenaida macroura) in Georgia, U.S.A. Weed Science, 57(06), 603-612. doi:10.1614/ws-09-046.1

Haig, S. M., Delia, J., Eagles-Smith, C., Fair, J. M., Gervais, J., Herring, G., . . . Schulz, J. H. (2014). The persistent problem of lead poisoning in birds from ammunition and fishing tackle. The Condor,116(3), 408-428. doi:10.1650/condor-14-36.1

Hernández-García, R. D., & Mellink, E. (2018). Population fluctuations of mourning doves (Zenaida macroura) in the state of Jalisco, Mexico, during 2004–2017. The American Midland Naturalist,180(1), 87-97. doi:10.1674/0003-0031-180.1.87

Meyers, P. M., Ostrand, W. D., Conover, M. R., & Bissonette, J. A. (2006). Assessing differences in mourning dove Zenaida macroura marginella nesting activity after 40 years. Wildlife Biology, 12(2), 171-178. doi:10.2981/0909-6396(2006)12[171:adimdz]2.0.co;2

Miller, D. A., & Otis, D. L. (2010). Calibrating recruitment estimates for Mourning Doves from harvest age ratios. Journal of Wildlife Management, 74(5), 1070-1079. doi:10.2193/2009-409

Otis, D. L., J. H. Schulz, D. Miller, R. E. Mirarchi, and T. S. Baskett (2008). Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi-org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/10.2173/bna.117

Plautz, S. C., Halbrook, R. S., & Sparling, D. W. (2011). Lead shot ingestion by mourning doves on a disked field. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 75(4), 779-785. doi:10.1002/jwmg.105

Poling, T. D., & Hayslette, S. E. (2006). Dietary overlap and foraging competition between mourning doves and eurasian collared-doves. Journal of Wildlife Management, 70(4), 998-1004. doi:10.2193/0022-541x(2006)70[998:doafcb]2.0.co;2

Rogers, A. M., Gibson, M. R., Pockette, T., Alexander, J. L., & Dwyer, J. F. (2014). Scavenging of migratory bird carcasses in the Sonoran Desert. The Southwestern Naturalist, 59(4), 544-549. doi:10.1894/mcg-08.1

Schulz, J. H., Gao, X., Millspaugh, J. J., & Bermudez, A. J. (2007). Experimental lead pellet ingestion in mourning doves (Zenaida macroura). The American Midland Naturalist, 158(1), 177-190. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2007)158[177:elpiim]2.0.co;2

Schulz, J. H., Reitz, R. A., Sheriff, S. L., & Millspaugh, J. J. (2007). Attitudes of Missouri small game hunters toward nontoxic-shot regulations. Journal of Wildlife Management, 71(2), 628-633. doi:10.2193/2006-352

Vuren, D. H. (2013). Avian response to removal of feral sheep on Santa Cruz Island, California. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 125(1), 134-139. doi:10.1676/12-102.1

At the time of this post, Kaitlyn Estep is a senior at the Evergreen State College. This post was made as a research project for the class Birds: Inside and Out in winter 2019.

Leave a Reply