Pigeon guillemot

Order:Charadriiformes

Family:Alcidae

Genus:Cepphus

Ready for take off, photo by Barry Troutman

Species:Cepphus columba

Introduction

The pigeon guillemot, Cepphus columba (pronounced, SEP-fus) is a seabird in the Alcidae family which includes auklets, puffins, murres, murrelets, and guillemots and referred to as alcids or auks. Members of the family can dive up to 200 meters and breed in colonies along the coast or on small islands. Pigeon guillemots are social birds but never form large flocks and stay relatively dispersed even on land. Based on BirdLife International data, the global distribution in 1993 accounted for 235,000 individuals and population trends consider the population stable and categorized as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List (2019). Factors that are likely to affect pigeon guillemot populations include oil spills, mammalian predators, habitat loss, and climate change (Ewens, 1992).

Unlike other members of this family, the pigeon guillemot maintains its presence in nearshore waters and in fact are a resident species in the Puget Sound and the only bird in the Alcidae family that breeds in the South Puget Sound (Lee & Green, 2017). In 2013, the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve Citizen Stewardship Committee put together a Quality Assurance Project Plan to begin surveying breeding colonies in South Puget Sound. The Nisqually Reach Nature Center (NRNC) is going into their 6th year monitoring pigeon guillemot breeding populations in the South Puget Sound contributing more data to assess populations in the Puget Sound. We know a lot about breeding colonies but there are still questions left unanswered. Since 2009 studies are focusing on using foraging ecology to tell us more about the community as a whole and monitor changes over time.

Pigeon guillemots commonly nest in colonies on rocky coast from Northern California up to Alaska (red line), but are less likely breeding in the lower portion of California (yellow line). They also breed in Japan, traveling down to the Kurile Islands in the Russian far east (Bixler, Roby, Irons, Fleming, & Cook, 2010; Seher, 2016). During the winter they stay near shore, from South California to parts of the Aleutian islands in Alaska (purple line).

Breeding adults are most recognizable by their striking black plumage, with bright red webbed feet and fiery red inner mouth, photo by Barry Troutman

Pigeon guillemot are medium sized birds with its body totalling about 30-35 cm and weighs 450-550 grams (Ewens, 1992). Similar to the black guillemot, they have round bodies, short-tails, small-heads, but have differing bill and neck lengths (Stokes, 2013). Pigeon guillemots instead have shorter necks, a steeper angled forehead, and short straight bill with its maxilla longer than with a slight hook. The feet are situated far enough back on the body allowing pigeon guillemots to come on land and with their webbed feet they can stabilize themselves. They also have claws that can be used to excavate burrows on sandy cliffs where they nest.

Winter plumage at Moss Landing (Elkhorn Slough), California, USA, photo from Wikipedia commons photographed by Derek Keats 10 30, 2016

Breeding adults are most recognizable by their striking black plumage, with bright red webbed feet and fiery red inner mouth.They have a distinctive white wing patch with slits that is very noticeable in flight. During the winter juveniles and adults alike sport a white lower belly and throat with a mottled black and gray upper, which extends to the forehead. During the winter they roam solo and are more elusive due to their dull winter coloration.

Egg shells are pale blue-green with grayaish brown speckled grayish brown, photos taken at Mill Bight, photo by Laura Milleville NRNC

They have a distinctive white wing patch with slits that is very noticeable in flight. During the winter juveniles and adults alike sport a white lower belly and throat with a mottled black and gray upper, which extends to the forehead. During the winter they roam solo and are more elusive due to their dull winter coloration. It has been documented that they molt soon after breeding season, shedding their remiges all at once, leaving the birds flightless (Thoresen,1958).

Pigeon Guillemots will breed on sand-clay bluffs, rocky shores, under rock crevices, but can also nest in man-made structures such as bird boxes and in pipes (Bishop, Rosling, Kind, Wood, 2016). During the winter they are often dispersed at sea and typically in front of breeding colony sites.

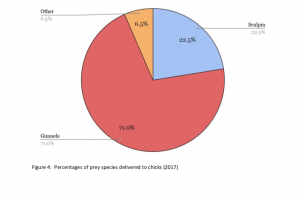

Pigeon guillemots diets consist of small fish, mainly gunnel, sand lance, sculpin, and rockfish, but also eat other.

Many studies have been conducted in conjunction with breeding surveys to monitor diet and increase our understanding why pigeon guillemots choose certain fish to serve their chicks. For example, a study that took place from 1979 to 1997 in the Prince William Sound, Alaska documenting diet preferences of pigeon guillemots to connect forage ecology concepts with reproductive success and chick growth. On a population level a correlation was discovered between specializing on high lipid fish and size of prey and effecting fledgling success (Golet, Kuletz, Roby, & Irons, 2015; Kreamer, 2012).

Pigeon guillemot courtship display vocals, recorded by Meena Haribal and uploaded to xeno-canto. Recorded in Sequim, a city in Clallam County Washington June 4, 2018. Observer noted two pairs bill clapping, nuzzling and circling one another each other. High pitch whistles can be heard close and from the distance, often repeated at different rates.

Pigeon guillemot song and call in the form of high and low whistles, recorded by Ed Pandolfino and uploaded to xeno-canto. Recorded in Mendocino California on July 11, 2015.

James Link, XC582547. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/582547.

(Recording by James Link for Evergreen’s SURF project summer 2020. Image cropped from Xeno-canto Sonogram provided on above webpage)

Social Behavior

Pigeon guillemots are sociable and semi-colonial, hanging out on land or in the water. Vocalizations range from trills and whistles to screaming. When threatened by others they use displays such as a hunch-whistle or lunge at their enemies. During the hunch-whistle display they send their head backwards making a whistle sound, also with bill open exposing their red lined mouth, and carpals completely open (Ewins, Peter, 1992). They’ve also been documented making hissing noises when lifted from their eggs (Thoresen and Booth, 1958).

Sexual Behavior

Pigeon guillemot birds are polyandry, sticking with one female year after year unless something happens to one of them over the winter. They are faithful to their breeding locations, returning to the same burrow unless it is deemed unsuitable for nesting. A detailed account of copulation was observed by Asa Clifford Thoresen and Ernest Booth while doing by surveys on Fidalgo Island, Skagit County Washington in 1958. When a female calls out to her male, she attracts him with her bright red mouth, while others chased and dodged one another as if playing some sort of water sport. When the pair then shows courting displays by billing and twittering, and finally the male circles the female before mounting on her rear. The entire copulation was reported as lasting 90 seconds.

The majority of alcids produce one egg, but the pigeon guillemot is unique by having a clutch size of two. Juveniles will reach sexual maturity between ages 3-5. It is still unclear what role juveniles contribute to the population.

Swimming and Flight

Pigeon guillemots are specialized divers, diving as deep as 10-30 meters, paddling with their wings and using their feet as rudders (Lovette & Fitzpatrick, 2016; Ewins, 1992). Their ability to dive sacrifices flight efficiency, causing the birds to flap their wings more energetically in order to stay up. Under water its been speculated that mating couples will swim together, chasing each other before surfacing to continue mating activities (Thoresen and Booth, 1958). Adults will perform synchronized flight patterns.

Pigeon guillemot populations are highly impacted by factors such as oil spills, impacts to nearshore habitats (direct or indirectly), shifting climate regimes causing a shift in available prey, and predation by introduced species (Kreamer, 2012). The Prince William Sound (PWS) in Alaska once had a historically significant population of Pigeon guillemot until the 1989 Exxon Valdezoil spill, killing many of them and decades later their populations have not recovered, therefore a restoration plan was established to address limiting factors associated with their decline and devise a course of action.

Prince William Sound, area highly impacted by the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill (photo from Wikipedia commons)

At the time of the spill the Prince William Sound (PWS) had approximately 4,000 pigeon guillemots nesting here and after the spill killed initially 500-1000 birds and has since been declining. The Naked Island groups, which includes three small islands in central PWS, has only 2% of shoreline in the PWS, nesting populations make up a quarter of the nesting population making it a desirable place to study.

By 2010, a report collected two years of data from the Naked Island group to investigate other limiting factors to declining populations (Bixler, Roby, Irons, Fleming, & Cook, 2010). It’s also been an established survey site since 1978 and after the EVOS spill nesting populations at the Naked Islands have declined by 47%. After oil was no longer a factor, new limiting factors were recognized, which included nest predation and availability of high quality prey (schooling forage fish) and predation by introduced species (American mink). Restoration for the Naked island group would potentially recover the population to 45%.

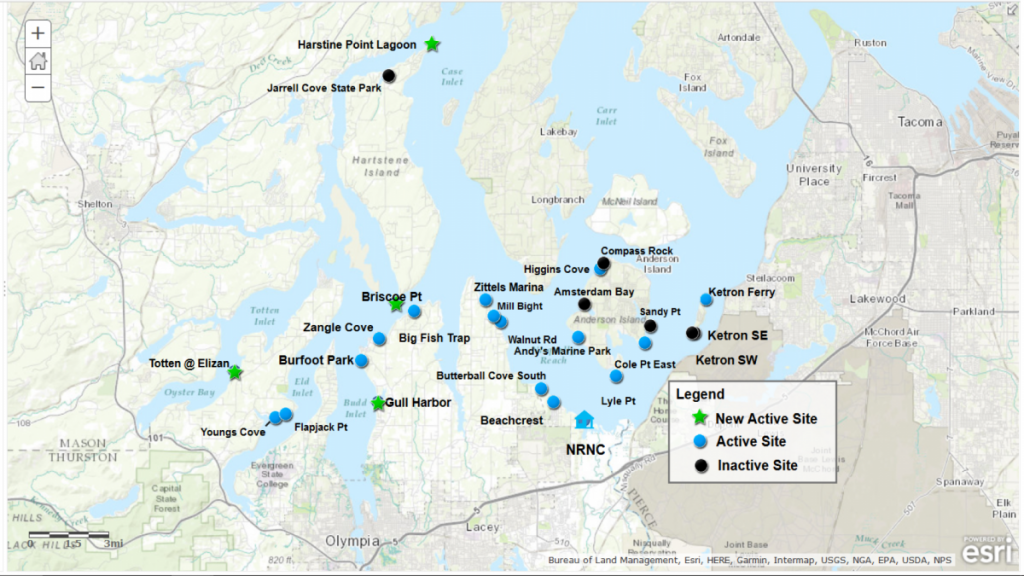

To gather more information about the presence of Pigeon Guillemots in the South Puget Sound, the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve Citizen Stewardship Committee (NRARCSC), assisted by the Washington Environmental Council (WEC) and the Washington Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) to initiate a monitoring pilot program in 2013 (Lee and Green, 2017). This is the first advancement of baseline data for pigeon guillemot breeding and nesting data for the South Puget Sound region. The Washington Department of Natural Resources manages the area and can use this data to help establish management objectives for the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve. The work will contribute to the mission to keep Puget Sound healthy.

To gather more information about the presence of Pigeon Guillemots in the South Puget Sound, the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve Citizen Stewardship Committee (NRARCSC), assisted by the Washington Environmental Council (WEC) and the Washington Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) to initiate a monitoring pilot program in 2013 (Lee and Green, 2017). This is the first advancement of baseline data for pigeon guillemot breeding and nesting data for the South Puget Sound region. The Washington Department of Natural Resources manages the area and can use this data to help establish management objectives for the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve. The work will contribute to the mission to keep Puget Sound healthy.

Goals for the Nisqually Reach Nature Center Pigeon Guillemot Breeding Surveys

- Contribute to the larger population database by including the Southern Puget Sound region and de-mask annual population trends (Lee & Green, 2017).

- Connect citizens with concepts in environmental and scientific research on accessible aquatic lands for education purposes as part of the Washington Department of Natural Resource Aquatic Reserve program (Mills, Lee & Joyce 2014; Lee & Green, 2017).

Data Tracking

In the South Puget Sound sites are found within the Nisqually Reach and scattered in Budd, Eld, Totten inlet. Volunteers go out early enough to get surveys done by 9am, collecting the number of adults seen within site limits, number of active burrows, number of visits to active burrows, fish delivery and type of species caught, and disturbance (e.g. boat traffic, beach walkers, other birds).

Here is a sample method to track weekly surveys.

Weekly surveys tracking method example June 2018 (handwritten version)

This is an example of an extended survey that was handwritten and later transferred to the online data tracking website.

Example of an extended survey at Walnut Road with schematic, 7-21-2018

A schematic is important to have with every survey to give the person reviewing the data a chance to observe what volunteers see on their visit. A schematic helps track active burrows and document changes in burrow activity.

Example schematic of Totten colonies 7-27-18

When surveys are completed volunteers enter data into the online database that also includes pigeon guillemot data from other parts of Washington. At a glance weekly surveys display how many pigeon guillemots are observed per visit, the tide and below that is observed activity including prey deliveries, type of prey, and a detailed view of each survey. To skip to a specific week, click the hyperlinked number and it will display other information observed during the survey period. To check out the online version click here >> http://www.pigeonguillemotdata.org/

Results

*Results are based on the 2017 Pigeon Guillemot Foraging and Breeding Survey in and near the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve monitoring report.

- In 2017 the percentage of prey species delivered to chicks accounted for 71% gunnel, 22.5% sculpin, and 6.5% were unidentified.

- 37 sites monitored in 2017 (6 more than the previous year)

- ~337 bird accounts (estimated to account for overlap)

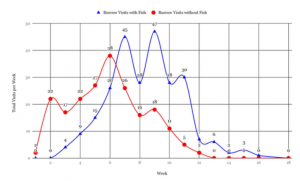

- Based on fig. 1 below, Peak burrow visits with prey occurred between week 7 and 9

- Based on fig. 1 below, by week 11 and 18 birds are beginning to move farther out to sea

BirdLife International 2018. Cepphus columba. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018:e.T22694864A132578338. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22694864A132578338.en. Downloaded on 13 March 2019.

Bishop, E., Rosling, G., Kind, P., & Wood, F. (2016). Pigeon Guillemots on Whidbey Island, Washington: A six-year monitoring study. Northwestern naturalist, 97(3), 237-246.Bixler, K. S., Roby, D. D., Irons, D. B., Fleming, M. A., & Cook, J. A. (2010). Pigeon guillemot restoration research in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Exxon Valdez, 6.

Cushing, D. A., Roby, D. D., & Irons, D. B. (2018). Patterns of distribution, abundance, and change over time in a subarctic marine bird community. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 147, 148-163.

Ewins, Peter, 1992. Pigeon Guillemot (Cepphus columba), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.).

Link:https://birdsna-org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/Species-Account/bna/species/piggui/introduction

Golet, G. H., Kuletz, K. J., Roby, D. D., & Irons, D. B. (2015). Adult prey choice affects chick growth and reproductive success in pigeon guillemots. The Auk; Jan 2000; 117, 1; ProQuest pg. 82

Green, A., Lee, T., & Center, N. R. N. (2018). Pigeon Guillemot Foraging and Breeding Survey in and Near the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve. The Nisqually Reach Nature Center. Olympia, Washington: Washington Department of Natural Resources Aquatic Reserves Program

Kreamer, K. A. (2012). Factors affecting the success of Pigeon Guillemots on Whidbey Island, Puget Sound, Washington, during the 2009 breeding season (Doctoral dissertation, Evergreen State College).

Lederer, R., & Burr, Carol. (2014). Latin for bird lovers : Over 3,000 bird names explored and explained. Portland, Oregon ; London: Timber Press.

Lovette, I., & Cornell University. Laboratory of Ornithology. (2016). Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s handbook of bird biology.(Third edition / edited by Irby Lovette, John W. Fitzpatrick. ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Mills, A., Joyce, J., & Council, W. E. (2014). Pigeon Guillemot Foraging and Breeding Survey in and Near the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve 2013 Monitoring Report.

Mills, A., Lee, T., Center, N. R. N., Joyce, J., & Council, W. E. (2014). Pigeon Guillemot Foraging and Breeding Survey in and Near the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve. Olympia, Washington: Washington Department of Natural Resources Aquatic Reserves Program

ROBINETTE, D. P., NUR, N., BROWN, A., & HOWAR, J. (2012). Spatial distribution of nearshore foraging seabirds in relation to a coastal marine reserve. Marine Ornithology, 40, 111-116.Seher, V. L. (2016). Breeding ecology of Pigeon Guillemots (Cepphus columba) on Alcatraz Island, California (Doctoral dissertation, San Francisco State University).

Stokes, D., & Stokes, Lillian Q. (2013). The new Stokes field guide to birds. Western region (1st ed., Stokes, Donald W. Stokes field guides). New York: Little, Brown &.

Vilchis, L. I., Johnson, C. K., Evenson, J. R., Pearson, S. F., Barry, K. L., Davidson, P., … & Gaydos, J. K. (2015). Assessing ecological correlates of marine bird declines to inform marine conservation. Conservation Biology, 29(1), 154-163.

Ward, E. J., Marshall, K. N., Ross, T., Sedgley, A., Hass, T., Pearson, S. F., … & Faucett, R. (2015). Using citizen-science data to identify local hotspots of seabird occurrence. PeerJ, 3, e704.

Wikipedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:North_America_blank_map_with_state_and_province_boundaries.png

Alison Flury is a student at the Evergreen State College, studying botany and integrated science programs. She enjoys volunteering with local organizations like Capitol Land Trust and the Nisqually Reach Nature Center. During the summer she enjoys bird watching, hiking, and volunteering in Olympia. Her favorite volunteer activity to do is collect wild flower phenology data on trails at Mount Rainier National Park with the Meadowatch Citizen Science program. Out on the hood canal she can be found spending time with partner and their dog Butters and cats Fiona, Boots, and lil boots. When she graduates from the Evergreen State College Winter 2019, she will go on to work with the City of Olympia to maintain park trails.

Alison Flury is a student at the Evergreen State College, studying botany and integrated science programs. She enjoys volunteering with local organizations like Capitol Land Trust and the Nisqually Reach Nature Center. During the summer she enjoys bird watching, hiking, and volunteering in Olympia. Her favorite volunteer activity to do is collect wild flower phenology data on trails at Mount Rainier National Park with the Meadowatch Citizen Science program. Out on the hood canal she can be found spending time with partner and their dog Butters and cats Fiona, Boots, and lil boots. When she graduates from the Evergreen State College Winter 2019, she will go on to work with the City of Olympia to maintain park trails.

Page edited 8/22/2020 by James Link to add a sound file

Leave a Reply