Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

Genus: Sphyrapicus

Species: Sphyrapicus ruber

Introduction

The Red-breasted sapsucker is a robin-sized woodpecker that feeds on sap from trees. It is about 20-22 cm in length and 69-48 g in mass (Walters, Miller, & Lowther, 2014).The Red-Breasted Sapsucker can only be found in western north america. This sapsucker shares the common woodpecker trait of nesting in cavities, and prefers to make its nest in snags (Tomasevic, & Marzluff, 2017). The red-breasted sapsucker is closely related to two other distinct species, the Red-naped Sapsucker (S. nuchalis) and the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (S. varius) with which it forms a superspecies (Walters et al, 2014). These three sapsuckers come into contact and form hybrid zones occasionally hybridizing (Seneviratne, Davidson, Martin, & Irwin, 2016).

Its plumage is dynamic with a red head that drapes down to its nape, and on the front falls to midway down the breast. The lower half of its belly is pale yellow. It has black and white lores contrasting its red head. Its wings are mostly black with a bold white strip following the outer contour of the wing, as well as some horizontal dashes of white down the lower half of the primaries and secondaries. Its back is black with two vertical rows of pale yellow dashes. Its bill is short for a woodpecker, straight, and chisel-tipped.

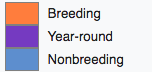

Found strictly on the west coast of North America. In the breeding season they are most commonly found from southeastern Alaska down the coastal ranges of B.C. Canada, west of the Cascade mountains in Washington and Oregon and into northern coast ranges of California. They are also found in the Cascades, and Sierra Nevada of CA (Shunk, 2016). Migratory populations largely breed east of the Cascades and winter in CA. Resident populations are found closer to the coast (Billerman, Murphy, & Carling, 2016). In their history they have expended their range greatly into the northeast of California and south-central Oregon (Billerman et al., 2016).

Range map:

Hybrid Zone:

Red-breasted and Red-naped Sapsuckers hybridize in a narrow contact zone that leads from B.C. Canada down into northern CA (Billerman et al., 2016). The Yellow-bellied and Red-breasted have a much more abbreviated hybrid zone in northern B.C. (Walters et al., 2014).

Habitat in breeding range is from sea level up to 9500 ft in mixed conifer forests containing white pine, Douglas-fir, spruce and western hemlock (Shuck, 2016). They are also found in deciduous and riparian habitat with quaking aspen, cottonwood, and red alder (Walters et al., 2014). Also further north in coastal mountains, they are found in old-growth Douglas-fir stands that are close to open areas caused by fire, logging or next to water (Shuck, 2016) In terms of the way deforestation affects their habitat, these sapsuckers benefit from partial cutting where forests contain both open areas and forested spaces due to their diverse foraging habits (Mahon, Steventon, & Martin, 2008).

Nests:

Red-breasted Sapsuckers are cavity nesters. They prefer to create their nests in snags (dead standing tress).When choosing a nest site, these birds find a balance between significant height to avoid predation of land animals and a lower point on the tree with a larger diameter, providing space for a larger cavity (Joy, 2000) These sapsuckers select large-diameter snags not only for space for larger nest cavities but greater insulation, especially for the birds at higher altitudes (Joy, 2000). Creating large nest cavities is necessary for the large clutch size of this species. They are also found to nest in aspen, alder and cottonwood. They typically lay a clutch of about 4-7 eggs (Bent, 1939). Nests generally are not re-used again in following breeding seasons (Joy, 2000).

Red-breasted Sapsuckers, as their name implies, feed on sap from trees. These birds’ diet are quite diverse though, as they feed on sap from a great many species of trees, as well as insects like ants, beetles and their larvae, spiders and flying insects that they catch on the wing, and occasionally fruit (Bent, 1939). These sapsuckers drill shallow holes (sap wells) to feed on xylem or phloem sap in many types of conifer and deciduous trees (Mahon et al., 2008). They usually drill many sap wells in one tree ordered in neatly spaced row. The bird will drill, leave, and return intermittently to feed on the sap that slowly oozes out (Kaufman, 2019). In breeding season they spend equal time drilling sap wells as foraging for insects in snags and live trees and flycatching (Shunk, 2016). They have been known to tap up to 2,000 wells per tree, and tend to tap the bottom portion of tree trunks in the winter to avoid freezing sap (Shunk, 2016).

Frank Lambert, XC408661. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/408661.

Drumming:

Frank Lambert, XC408658. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/408658.

Nesting:

The male and female of a pair share parenting responsibilities. Both sexes participate in incubation, the male taking the night shift and part of the day and the female taking the dayshift (Kaufman, n.d.). Both parents also collect food and feed young. The fledglings leave the nest around 23-28 days after hatching (Kaufman, n.d.).

For more info on nest type, see nests section under the “Habitat” tab.

Voice:

The Red-breasted sapsucker sound similar to the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, more like a “mewing”, and less drawn out than that of the yellow-bellied. (Winkler, Christie, & Nurney, 1995)

Both the males and females drum. The rhythm is an initial burst followed by irregular slower bursts of 2-3 strokes (Winkler et al, 1995)

Mating:

The mating behavior of the males is to erect the feathers on their head and have drooping wings (Winkler et al, 1995). Another courtship display is pointing bill into the air and swaying side to side (Kaufman, n.d.). Pair bonds are monogamous and persist through the breeding season, and usually as well as in following years. The loyalty of the pair may be at least in part due to nest site loyalty (Walters et al, 2014)

Agression:

Red-breasted Sapsuckers engage in acts of aggression towards threats vocally and physically. They use acoustic aggression (calling and drumming) but not as much as their relatives the Red-naped Sapsucker and may rely more on visual cues like head bobbing, tail flicking and spreading (Billerman, Carling, 2016)

January 18, 2019 11:20am

Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge

Olympia, WA

47.07821,-122.70891

I spotted a male Red-breasted Sapsucker about 100 ft up in a large broad-leaf maple tree. I found it by following a waterfall of moss that was dropping from the tree quite conspicuously. It was pecking at the mossy bark. I got an excellent view of its red head and black back with white bars. After a few minutes I heard a squak-like bird call and saw a second Red-breasted Sapsucker fly up and land on the same tree about 2 ft above the original one and this one began the same behavior. I watched for a few minutes and then they both flew off. Neither were drumming or making noise so I presume they were scavenging for insects as opposed to making a nest hole or digging a sap well.

Bent, A.C. (1939). Life Histories of North American Woodpeckers. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Billerman, S.M., & Carling, M.D. (2016). Differences in aggressive responses do not contribute to shifts in a sapsucker hybrid zone. The Auk, 134(1), 202-214. http://doi.org/10.1642/auk-16-142.1

Billerman, S. M., Murphy, M. A., & Carling, M. D. (2016). Changing climate mediates sapsucker (Aves: Sphyrapicus) hybrid zone movement. Ecology and Evolution, 6(22), 1-15. http://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2507

Joy, J.B. (2000). Characteristics of Nest Cavities and Nest Trees of the Red-Breasted Sapsucker in Coastal Montane Forests. Journal of Field Ornithology, 71(3), 525-530. http://www.jstor.org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/stable/4514517

Kaufman, K. (n.d.) Red-breasted Sapsucker. Audubon Guide to North American Birds. Retrieved from: http://audubon.org/fieldguide/bird/red-breasted-sapsucker

Mahon, C. L., Steventon, J.D., & Martin, K. (2008). Cavity and bark nesting bird response to partial cutting in Northern conifer forests. Forest Ecology and Management, (256), 2145-2153: doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2008.08.005

Seneviratne, S. S., Davidson, P., Martin, K., & Irwin, D. E. (2016). Low levels of hybridization across two contact zones among three species of woodpeckers ( Sphyrapicus sapsuckers). Journal of Avian Biology, 47(6), 887–898. https://doi-org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/jav.00946

Shunk, S.A. (2016). Peterson Reference Guide to Woodpeckers of North America. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Tomasevic, J., Marzluff, J. (2016). Cavity nesting birds along an urban-wildland gradient: is human facilitation structuring the bird community? Urban Ecosystems, 20(2), 435–448. https://doi-org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s11252-016-0605-6

Walters, E. L., E. H. Miller, and P. E. Lowther (2014). Red-breasted Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus ruber), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Retrieved from Birds of North America: https://birdsna-org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/Species-Account/bna/species/rebsap

Winkler, H., Christie, D.A. & Nurney, D. (1995). Woodpeckers: A Guide to the Woodpeckers of the World. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company.

It seems as though the Red-breasted Sapsucker is special in that predictions show that the changing climate may actually benefit them through expansion of their preferred habitat. These sapsuckers are found in a wide range of precipitation seasonality variables, and in moderate to warm winter temperatures (Billerman et al, 2016). A study found that in future climate scenarios the Red-breasted Sapsucker’s range will expand significantly further east than their current range (Billerman et al, 2016).

As a consequence of this changing habitat via climate change, the preferred habitat of their relatives the Red-naped Sapsucker is predicted to significantly decrease, isolating them to higher elevations. This impacts the hybrid zone of the two species, narrowing the overlap of range distribution significantly meaning in the future there will be far less opportunities for hybridization (Billerman et al, 2016).

Additionally, humans currently and will continue in the future to have an influence on the survival of the species. As a cavity nester, the sapsucker is reliant on the existence of snags, the habitat which it favors for nesting. Human encroachment upon such habit comes in forms of deforestation practices and urbanization. Studies have shown that clear cutting, and logging practices that do not leave behind standing dead trees greatly reduce population sizes of this sapsucker (Joy, 2000). Along with loss of mature forests, urbanization impacts this species. In a study looking at primary cavity nesters, the Red-breasted sapsucker was found to never use anthropogenic substrates or nesting opportunities (Tomasevic, Marzluff, 2016). In urban areas where forest cover is below 16% primary cavity nesters have been found to start disappearing. This also has a downstream affect on the secondary cavity nesters who although make more use of anthropogenic nesting, still heavily on the birds like the sapsuckers who excavate homes for them (Tomasevic, Marzluff, 2016).

Leave a Reply