Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

Genus: Aythya

Species: A. collaris

Picture taken by: Stephanie Shipp in Nisqually Wildlife Refuge

The ring-necked duck is a medium sized duck in which both sexes have a distinctive bill that has white ring at its base followed by a gray stretch followed by another white ring and a black tip. The males have a black head that has a faint iridescent sheen on it when seen the right way, with golden eyes and a brown ring around their necks. They have light gray to white on their sides, flanks, and bellies. Females are not as strikingly colored as the males. They are generally a brown gray with a dark brown cap on their heads running from the supercillium to the crown to the back of the neck with a pale eye ring and a white chin. The juveniles are similar in coloration to their adult sexes, they just tend to be lighter colored (Hohman et. al. 2012, Ring-Necked Duck. 2016)

Picture taken by: Stephanie Shipp at the Nisqually Wildlife Refuge

Males are only slightly larger than the females, with males weighing 542 to 910 grams, and being anywhere from 40 to 46 cm in length. The the females on the other hand can weigh from 490 to 894 grams and are typically 39 to 43 cm long (Hohman, et. al. 2012).

Distribution

Ring-necked ducks are found throughout North America ranging from Alaska to as far south a Mexico. Though there have been sightings in other locations there has not been anything concrete (Hohman et. al. 2012, Kaufman, K 2016).

To view a map of the distributions visit All About Birds or Birds of North America or Audubon (Ring-Necked Duck. 2016, Kaufman K., 2016, and Hohman, et. al. 2012).

Habitat

Ring-necked ducks dwell primarily in freshwater marshes at all of their life stages but will rest, during migration, in smaller and shallower ponds such as those found on cattle farms (Roy, 2018, Mason, et. al. 2013, Hohman, et. al. 2012).

Food Habits

Both sexes are generally herbivorous, but the males will on occasion consume macro-invertebrates. However, during breeding season the females will consume more macro-invertebrates, while the males will, generally, not increase their macro-invertebrate consumption (Eberhardt and Riggs, 1995). The females increase the number of macro-invertebrates they consume to help with the production of the eggs.

In general, paired males and females will lose weight during the breeding season, but the females will lose a lot more than the males due to the fact that the females almost exclusively use their lipid reserves, while males use those reserves as well as forage for themselves (Hohman, 1986).

Ring-necked ducks are diving ducks. Because of this, according to Reynolds et. al., 2015, they help transport Echinochloa colonum which is an invasive grass like weed.

Sounds

The ring-necked duck tends to make a quiet quacking sound that is higher pitched than a Mallard. They also can make a quiet high pitched peeping. Unfortunately there is not much else to say about the sounds that ring-necked ducks make (Hohman et. al. 2012, Ring-Necked Duck. 2016).

To listen to ring-necked duck vocalizations visit All About Birds and Birds of North America and Audubon (Ring-Necked Duck. 2016, Kaufman K., 2016, and Hohman, et. al. 2012).

Behavior

For the early stages of their lives ring-necked ducks will follow their mothers until they become independent. It was noted in a study that females in an area of Minnesota tend to nest within 500 meter of a road in a freshwater marsh, and will move the chicks as soon as they hatch to areas of more open water where the brood tends to remain until the ducklings fledge. After this stage they tend to follow other members of their species for migrations and foraging (Roy, 2018, Roy and Herwig, et. al. 2014).

Their molting ecology is variable by sex and time of year, though it is specifically different between the sexes during May and April for both the adults and juveniles (Hohman and Crawford, 1995).

Field Notes

Date: Feb. 24 2019

Location: Nisqually Wildlife Refuge

Coordinates: 47.07456, -122.71330

Weather: Mostly cloudy with a strong wind coming from the Northwest.

Observed 4 male ring-necked ducks foraging/diving in the central pond in the Nisqually Wildlife Refuge. They were observed for about 10 minutes with a total of 19 dives. The duration of the diving was on average 13 seconds.

Picture taken by: Stephanie Shipp in Nisqually Wildlife Refuge

Date: Feb. 25 2019

Location: Nisqually Wildlife Refuge

Coordinates: 47.07301, -122.71269

Weather: Partly cloudy with a strong wind blowing from the Northwest

Observed 5 male ring necked ducks diving/foraging. I was not able to observe them for long so I didn’t make note of diving duration, but I did notice that one of the males had green on the white and gray feathers on his wing, possibly due to algae growth, but it was hard to tell.

Population Trends and Conservation Issues

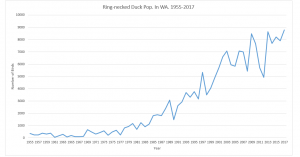

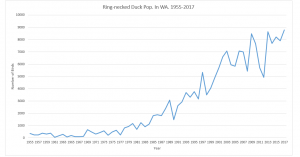

According to several studies conducted in Minnesota and Maine the number ring-necked duck breeding pairs and the survival rates of the broods are on the decline (Schummer, et. al. 2011, Zicus et. al., 2013). However according to the numbers from the Audubon Societies Christmas Bird Counts the ring-necked duck populations have been on the increase both in Washington State and in the U.S.A as a whole (National Audubon Society, 2010). (The files for the entire USA for the years of 2016 and 2017 were too large to be downloaded from the National Audubon Society.) This is backed up by Zimpfer et. al. 2009 that found there was a one percent increase in the breeding population of the ring-necked duck in North America from 2008 to 2009.

A graph of the number of observed Ring-Necked Ducks in Washington State during Christmas Bird Counts from 1955 to 2017, data collected online from the National Audubon Society, 2010.

A graph of the number of observed Ring-Necked Ducks for the USA during Christmas Bird Counts from 1955 to 2015, data collected online from the National Audubon Society, 2010.

However, even in the areas where the ring-necked duck population seems to be on the decline it is still unknown as to what could mitigate it. A study by Haugen et. al. 2015 predicted that cutting the hunting bag limit of ring-necked duck by fifty percent results in only a one percent reduction in ducks harvested.

In regards to refuge use, ring-necked ducks seem to use them as a way to escape hunting pressure, often staying in refuges during hunting hours. According to Roy and Fieberg et. al. 2014, ring-necked ducks are more likely to use a refuge during the day and to leave a refuge at night.

Literature Cited

Eberhardt, R. T., & Riggs, M. (1995). Effects of sex and reproductive status on the diets of breeding ring-necked ducks (Aythya collaris) in north-central Minnesota. Canadian journal of zoology, 73(2), 392-399.

Haugen, M. T., Vrtiska, M. P., & Powell, L. A. (2015). Duck species co‐occurrence in hunter daily bags. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 39(1), 70-78.

Hohman, W. L., & Crawford, R. D. (1995). Molt in the annual cycle of Ring-necked Ducks. The Condor, 97(2), 473-483.

Hohman, W. L., Eberhardt, R. T., Herwig, C. M., & Roy, C. L. (2012). Ring-necked Duck (Aythya collaris) (A. F. Poole, Ed.). The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.329 Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Hohman, W. L. (1986). DUCKS (AYTHYA COLLARIS). The Auk, 103, 181-188.

Kaufman, K. (2016, March 04). Ring-necked Duck. Retrieved March 5, 2019, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/ring-necked-duck

Mason, C. D., Whiting, R. M., & Conway, W. C. (2013). Time-activity budgets of waterfowl wintering on livestock ponds in Northeast Texas. Southeastern naturalist, 12(4), 757-769.

National Audubon Society (2010). The Christmas Bird Count Historical Results [Online]. Available http://www.christmasbirdcount.org [March, 3, 2019]

Reynolds, C., Miranda, N. A., & Cumming, G. S. (2015). The role of waterbirds in the dispersal of aquatic alien and invasive species. Diversity and Distributions, 21(7), 744-754.

Ring-necked Duck. (2016, March 04). Retrieved March 5, 2019, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/ring-necked-duck

Roy, C. (2018). Nest and brood survival of Ring-necked Ducks in relation to anthropogenic development and wetland attributes. Avian Conservation and Ecology, 13(1).

Roy, C. L., Fieberg, J., Scharenbroich, C., & Herwig, C. M. (2014). Thinking like a duck: fall lake use and movement patterns of juvenile ring-necked ducks before migration. PloS one, 9(2), e88597.

Roy, C. L., Herwig, C. M., Zicus, M. C., Rave, D. P., Brininger Jr, W. L., & McDowell, M. K. (2014). Refuge use by hatching‐year ring‐necked ducks: An individual‐based telemetry approach. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 78(7), 1310-1317.

Schummer, M. L., Allen, R. B., & Wang, G. (2011). Sizes and Long-Term Trends of Duck Broods in Maine, 1955–2007. Northeastern Naturalist, 18(1), 73-87.

Zicus, M. C., Rave, D. P., Fieberg, J. R., Giudice, J. H., & Wright, R. G. (2013). Distribution and abundance of Minnesota-breeding Ring-necked Ducks Aythya collaris. Wildfowl, 58(58), 31-45.

Zimpfer, N., Rhodes, W., Silverman, E. D., Zimmerman, G., & Koneff, M. D. (2009). Trends in duck breeding populations, 1955-2009.

Leave a Reply