By Ken Thomas (KenThomas.us(personal website of photographer)) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Family: Emberizidae

Genus: Melospiza

Species: Melospiza melodia

Introduction

The Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) is a common and widespread bird. Although they are small, only about 6.25 inches long with a 8.25 inch wingspan and weigh only about 0.7 ounces, their prominent streaking pattern makes them standout (Sibley 2003). The Song Sparrow has numerous subspecies that vary in appearance considerably across its expansive range. This is due to divergent genetic characteristics developed by the subspecies’ in order to adapt to their assorted environments (Proctor and Lynch, 1993). Song sparrows can be relatively long lived song birds, as one individual survived for eleven years and four months in Colorado (Pwrc.usgs.gov 2014).

As its name implies, the Song Sparrow is best known for its complex and melodious songs. It learns these songs from other sparrows, and uses them to secure territories and mates (Arcese et al. 2002). It is usually easier to hear Song Sparrows than see them. Fortunately they are equally as pleasing to listen to as they are to watch (Mudge Pers. Obs.).

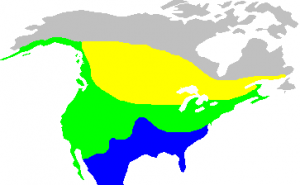

Song Sparrows are common and widely distributed throughout most of North America. They summer on their breeding grounds in Canada, then migrate south to winter in the southern U.S. and Mexico. Some Song Sparrows are year-round residents of their region (Arcese et al. 2002).

By Surachit [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Yellow = Summer (Breeding)

Blue = Winter (Non-breeding)

Green = Year Round

Across their very extensive range Song Sparrows take on many different appearances. For example, Song Sparrows of the South Western deserts are much paler than their counterparts that dwell in the Pacific Northwest (Sibley 2003). In general, song sparrows in wet coastal climates have a much darker plumage (Allaboutbirds.org). Alaskan Song Sparrows are not only darker, but also much larger than their Southern neighbors. This is due to Bergmann’s rule that states that within a species individuals residing in colder climates will be larger than those in warmer climates (Proctor & Lynch, 1993).

By Alan Vernon (Flickr: Song Sparrow in tree) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Song Sparrows are widespread and can be found in many of the North American habitats. Arctic grassland, desert shrub, Pacific rainforest, deciduous woodlands and suburbs are only a few of the places in North America that Song Sparrows inhabit (Arcese et al. 2002). Song Sparrows are not afraid of human habitation, often establishing territories and foraging in very close proximity to humans (Pinnow Pers. Obs.).

By D. Gordon E. Robertson (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

Song Sparrows walk or hop while foraging on the ground or in low vegetation for their diet of seeds, fruits, and invertebrates such as worms, spiders, dragonflies, and caterpillars. (Allaboutbirds.org). When foraging for seeds Song Sparrows will scratch at the ground with both feet and do a short hop forward immediately followed by a short hop back to the original position. This effectively pries lose any dirt and debris (Pinnow Pers. Obs.) Plants that Song Sparrows regularly consume include sunflowers, buckwheat, berries, clover, ragweed, rice, and wheat (Allaboutbirds.org).

Song Sparrows sing to defend their territory or nest; or raise an alarm call to warn of a danger or potential predator (Hatch 1997). The ability of males to learn songs is very important. They can have repertoires of 4-13 distinctly different types of songs (Reid et al. 2004). These songs vary greatly over their range, and tend to have lower notes in populations with territories near roads and other urban areas (Wood and Yezerinac, 2006). Studies have shown that males with larger repertoires are more likely to be able to find a mate than those with smaller repertoires (Reid et al. 2004).

Although repertoire size is a good indicator of reproductive success, it may not be as good at predicting territorial success. Studies indicate that song sharing is a much more critical element for acquiring and holding territory (Reid et al. 2004). In general, the greater the number of songs a bird shares with his neighbors, the greater his territorial success is (Beecher et al. 2000). Juveniles will often eavesdrop on adult males, learning songs and how to interact with neighbors, or “counter sing” (Templeton et al. 2010). Song sharing also helps increase repertoire size, so the two are closely linked (Beecher et al. 2000). Song sharing among Song Sparrows occurs in populations throughout their range (Foote & Barber, 2007).

Male song sparrows are very territorial and it seems that their songs can be used as territory defense (Nowicki et al. 1998). If a male sings and his neighbor replies with the same song, or type match, was thought to be perceived as a challenge (Burt et al. 2001). In another, more recent study, it type match seems to be an early threat signal (Akay et al. 2013).

While watching song sparrows, look out for their threat displays. One display, “Ballooning”, is exclusive to territorial males or persistent intruders. The bird puffs up and repeats a quiet song. Another display is the “Puff-sing-wave”. The feathers are puff out, the wings vibrate and in song, the bird flies slowly toward challenger or mate (Wise 1943).

It was originally thought that song sparrows could not tell the difference between neighbors or strangers by listening to their songs (Stoddard et al. 1991). However, these sparrows actually do associate certain songs with certain territories, thus the whether the bird is a neighbor or stranger (Stoddard et al. 1991). Females can also tell the difference between neighbors and strangers by song, and can even distinguish their mate’s song (O’Loghlen and Beecher 1999). Furthermore, adult male song sparrows tolerate juveniles during their song learning and memorization period (Templeton et al. 2012).

By Basar (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

Call 2:Song Sparrow Call 2

Song 1:Song Sparrow Song 1

Song 2:Song Sparrow Song 2

Song 3:Song Sparrow Song 3 (whisper)

Song 4:Song Sparrow Song 4 (San Juan Island)

Song 5:Song Sparrow Song 5 (Grays Harbor NWR)

(All sounds were recorded by the author at The Evergreen State College campus behind the Lab 2 building on November 14, 2012, at Seminar II on November 16, 2014, at Kanaka Bay, San Juan Island on November 23, 2014, or by Megan Lewis at the Grays Harbor NWR on October 22, 2014)

By Tony Alter from Newport News, USA (Song Sparrows Nest) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

By Tony Alter from Newport News, USA (Freshly Hatched) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Song sparrows are predominantly monogamous, but some song sparrows produce offspring with numerous mates each year (Sardell et al. 2012). Some twenty eight percent of all chicks are fathered by males other than a female’s mate, while thirty three percent of broods have chicks that are fathered by multiple males (Sardell et al. 2012) After their female begins laying eggs, the non-monogamous males will journey into neighboring territories in quest of fertile females that will welcome his advances (Akay et al. 2012). In these situations males must choose between taking care of his mate and young at home or pursuing extra-pair copulations (Akay et al. 2012).

By Tony Alter from Newport News, USA (Crowded Nest) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Date: November 12

Climate: 43°, sunny, light wind (5-10 mph)

Latitude: 42°04’21.66” N

Longitude: 122°58’34.34” W

Observation time: 2:16 PM – 2:26 PM

After two hours of searching around the Evergreen Campus, I finally found a pair of song sparrows near the Seminar II bird feeder. Though the observation time was short I did witness some interesting behavior. One of the two was much more upset then the other by the song I played to find them with, and I do believe now that it was male. He constantly wing flipped and darted around within some ferns, making close passes by my feet multiple times. The other individual, who I believe was a female, would often stay put for long periods of time, seemingly calm and uninterested.

The two then flew over to the ground below the feeder where they foraged, occasionally pecking and scratching at the dirt with their feet. The possible male then began pursuing the other bird. The possible female would hop or fly a few feet, the male would follow and land right where the female was perched (usually in a snow berry bush), which would make her take off and move a short distance again right before he touched down. This went on for a few minutes and at one point, I even thought I saw a display. The bird lowered itself a little, slightly outstretched its wings and fluttered them quickly. After more recent observations, I have seen this behavior a few times while a male is singing quietly, and it is possible that I missed the song. The birds then left the feeder and disappeared past some ferns, were I was unable to relocate them, even with song callbacks.

Date: November 13

Climate: 43°, overcast, light wind (5-10 mph)

Latitude: 47°04’21.26” N

Longitude: 122°58’44.94” W

Observation time: 11:10 AM – 12:00 PM

Early in my observations I played the songs and calls of the sparrow to find the birds on campus. While I only play calls or songs if it’s incredibly necessary now, it was interesting then to see how the sparrows responded to the sounds. In my experiences, it does not matter what song or call you play, a feisty male will always appear and reply if he heard the sounds. It actually really seems to upset them.

During this observation near the Seminar I bird feeders, I noticed for the first time how the sparrow reacted to the sounds of other birds too. Knowing that the two yellow flowered bushes across ftom the Seminar I feeders were often a hot spot for a male song sparrow, I headed over, stood in front of the bush #1 and played the song. This of course made the bird erupt out of the bush, perch and dart around on the top branches, wing flipping aggressively and emitting sharp to quiet chirps while scanning for that “bird” that was making the song. There are times when it takes a sparrow awhile to calm down after hearing the “ghost calls”, while there are times when the bird goes back to doing it business within a minute or two. This time, the bird calmed down quickly from the “ghost song” and quietly chirped periodically without wing flips while perched on a branch near the top of the bush. However, the sparrow sped up its chirps when a few black-capped chickadees arrived nearby, as well as when a man dragging a garbage can walked past. After a few more minutes of quiet chirps, the bird flew to yellow flowered bush #2 and fell silent. I soon got up from sitting next to bush #1, and stood silently about five feet away from bush #2.

After a few minutes, he re-emerged from the bush #2 when some dark-eyed juncos started chattering. He then flew to a branch about six feet off the ground in a paper birch tree that grows out of the bush, joining the juncos, which were higher up. From there he chirped lightly and a spotted towhee flew up and perched on a branch next to him. Then the sparrow’s wing flips began when a Steller’s jay began its raspy calls from a tree above, to which the sparrow called back with chirps, tilted its head to the side, and scanned the sky. The song sparrow then yawned. The Steller’s jay soon took off so everyone calmed down and sat quietly in the tree, the towhee and sparrow at eye level with me just five feet away. They all seemed fine with being so close to me, even when I would write in my journal or turn my head. They would occasionally look at me but more time was spent looking at other things. There were even no wing flips from sparrow, which is like a compliment now.

After a few awesome minutes of standing with the birds, the sparrow flew across the path and under the ferns beside the bird feeder, calling rapidly then falling silent. I stayed where I was. He soon hopped out from under the ferns and began eating seeds on the ground beneath the feeder, then headed right back under the ferns. It wasn’t long before he hopped back out to the feeder and this time he stayed longer, scanning and wing flipping while scratching and pecking at the ground and breaking seeds in his bill. Wing flips increased when a pair of Anna’s hummingbirds darted quite close past him as they chased each other. A pair of spotted towhees then joined the sparrow at the feeder and one of the individuals went after the sparrow, who had a seed in his bill. Soon after, the sparrow flew back to yellow flowered bush #1, one of the towhees followed only a few feet behind him and perched on a branch at the top of the bush, while the sparrow hopped deep inside, near the base, where I could hear him shuffling dead leaves.

Date: November 15

Climate: 46°, sunny, slight wind (5 mph)

Latitude: 47°04’21.26” N

Longitude: 122°58’44.94” W

Observation time: 3:20 PM – 4:20 PM

When I arrived at Seminar I, I spotted the sparrow as it foraged on the ground below the feeders but he then flew to his favorite yellow flowered bush #1 straight across the path (followed by a towhee), perched at one of the top branches, and wing flipped away. His wing flips increased in occurrence and speed when a dog and two people walked past, and again when another person passed. He then hopped down the ground deep within the bush where I lost sight of him and could only listen for him shuffle around in the dead leaves. About twenty minutes later, he flew over to yellow flowered bush #2 for a few minutes before he headed back to the top of bush #1. He then wing flipped and rushed at a dark-eyed junco when it landed in the bush, which displaced the junco. The sparrow then returned to the top of the bush and scanned, occasionally wing flipping and cleaning his bill by scraping it across the bark of the branch he was perched on. After a while he went back into the depths of the bush but soon re-emerged and rushed another junco, which made the bird fly away. After some more scanning, he flew over the ferns beside the feeder, and periodically popped out and foraged on the ground at the bottom of the feeders before hopping back into the ferns.

Date: November 16

Climate: 43°, sunny, slight wind (5 mph)

Latitude: 47°04’22.39” N

Longitude: 122°58’34.70” W

Observation time: 2:09 PM – 4:09 PM

I was struggling to find a song sparrow this day but while playing the song in the Seminar II garden, I was surprised to hear a quiet reply nearby. The sparrow was perched on top of a skinny stump about four feet off the ground as it scanned around and slightly wing flipped. It then flew across a path and landed on the ground between some ferns and a young (pine?) tree where it began to sing quietly for a bit, then just stood there and looked at me from about five or six feet away, quietly chirping to itself at times. No wing flips. I could see the quick rise and fall of his chest as he breathed and his little black eyes as they blinked. Eventually he fell silent, but for some reason continued to stand close to me and scan around, up at me at times. Still no wings flips. He was a pretty calm bird.

After a while he began to forage along the ground in the wood chips, scratching with his feet and pecking. He hopped in and out of the ferns and nearby bushes until I lost track of him. I didn’t want to loose him so after a few minutes, I played the song again and he flew up on a nearby handrail and sang quietly back again. That’s when I noticed that when he sang he often opened up his wings slightly and fluttered them extremely fast. Again he hopped over to me on the ground, this time about three feet, his neck outstretched as he looked at me. He then flew on to a branch of the young pine tree and continued to sing quietly for another estimated twenty times in a row, with some variations, before he flew over to a huckleberry bush and ate a few berries from the branches of the bush and along the ground below it. When startled it seemed that the bird always flew into a nearby holly bush, maybe for protection?

While the sparrow was in the holly bush, I discovered two more song sparrows at the feeder. One of them was singing while the other actually fed from the feeder, not on the ground beneath it. Feeding from the feeder does not go without excessive wing flips. Both individuals often flew up over the short wall across from the feeder and into some snow berry bushes. Soon after, the original sparrow joined the other two. After a few minutes the singing stopped and I lost track of all but one of the birds, which was foraging along the ground beneath and around the feeder, scratching with its feet and pecking. A spotted towhee, which are always around the sparrows, made a charge at the foraging bird, which lept about a foot away from the towhee. Then another one of the sparrows returned and fed directly from the feeder again, which is something that seems rare for the song sparrows on campus. He then dropped back down to the ground, sang and pursued the other individual. The third bird soon appeared again too and it was this reoccurring scenario of one bird (a female?) trying to forage or escape the singing male who was chasing her around (no physical contact made) and the third bird would just seem to follow slowly behind and watch, sometimes staying to forage under the feeder while the other two flew over the wall. Towards the end of the observation, a towhee made another charge at one of the sparrows which lept away again.

Date: November 17

Climate: 46°, sunny, slight wind (5 mph)

Latitude: 47°04’19.89” N

Longitude: 122°58’33.76” W

Observation time: 1:20 PM – 3:20 PM

While I was headed over to check the Seminar II feeder, I overheard an upset song sparrow towards the library loop. I investigated and found the bird behind the Seminar II building, on a wall at the stairwell the leads down to the pathway the runs along the back of the building. Something had really upset the bird, as it was wing flipping, but also doing what I call “body flipping”, which is when the body is also flipping around, side to side, back and forth, around and around, while also wing flipping. The bird was also emitting some really loud and constant calls. After a few minutes, the bird hopped down from the wall, flew into a young (fir?) tree, and darted to the ground where it disappeared from view into the forest. He chirped for a bit more before going silent.

I did not want to lose the bird so I played a call. He appeared on a low branch of another young (fir?) tree and sang quietly. He then flew past me and landed in a tree near the stairwell again where he scanned around and wing flipped. He soon calmed down, stopped wing flipping, and began preening, working the breast, belly, scapular, and primary feathers. The wing flips picked up again before he took off back into the forest. Lost it again so after while I played the song again. He came out from under more young (fir?) trees and quietly sang again. He then flew across the path and sang a few more times before darting under some ferns, huckleberry, and holly bushes. I believe he was foraging underneath all the growth as I could hear him shuffling around and possibly scratching with his feet. When he does come into view, he is pecking through the dirt. He then hopped on to the concrete stairwell and began pecking in the little grooves on each step that I assume help for traction when we walk on them. The grooves held seeds needles that the sparrow was sorting through. He often cracked and crushed the seeds and needles in his bill, letting the unwanted material drop from his bill or it was tossed. He made a quick trip to the ground underneath the huckleberry bushes and ferns before returning to some different steps and sorting through the grooves again. Another short trip over to the berry bush before he flew off into the forest.

Date: November 19 Part 1

Climate: 43°, partly sunny, slight wind (5 mph)

Latitude: 47°04’21.28” N

Longitude: 122°58’46.68” W

Observation time: 10:55 AM – 12:55 PM

I could not find a song sparrow at the Seminar I feeders so I headed over to the Long House garden I looked for any movement and listened for any rustling. Where were the sparrows? I played the song and calls and heard the unmistakable sound of an upset song sparrow. He was well hidden inside a (fir?) tree and he wing flipped, body flipped, scanned, and chirped for five minutes after I played the sounds. He then fell silent and flew off but after a while he was back in the same tree, occasionally chirping. This was interesting; he then flew to a possible paper birch tree a few feet away from the presumed fir tree and hopped up until he was about twenty feet off the ground. I had never seen a song sparrow more than six or seven feet off the ground until this moment. A pair of spotted towhees soon joined the sparrow and perched just a few feet away from him. A man rolling a loud cart passed slowly by and the birds were eyeing him. They then all fell silent as soon as he was gone.

As the sparrow took off and dropped back down towards some bushes below, one of the towhees followed and seemed to tackle/bash the sparrow just as they both entered the bush. They made a pretty big crash sound into the bushes. The towhee then chased the sparrow momentarily in the bush before the sparrow hopped out onto a rock. He began to forage through dead leaves on the ground but constantly wing flipped, body flipped, and chirped as he scratched and pecked. He then headed into some tall marshy grass and fell silent.

I played the song to find the sparrow again after a while. He sang back a whisper of a song and outstretched his wings slightly, fluttering them at an amazing speed. He also preened his chest feathers multiple times, body popped, chirped, and then descended to the ground to forage through the tall grass. When I observe the birds I sit or stand still and am very quiet. However, I finally decided to move to a different position in the garden to get a better look at the bird. I’m not sure if the bird heard me move but he seemed really upset when he emerged from foraging the long grass and saw that I was sitting like statue on the bridge instead of up on the gravel hill because he got upset. Body popping, wing flipping, loud chirping, darting around, the whole thing. I had not encountered a sparrow that got so overly upset at things until this guy. Suddenly, he went abruptly silent. It took me a bit to figure out that he had headed to the yellow flowered bushes across from the Seminar I feeders. Another sparrow was there too, mostly feeding along the ground below the feeder, but both sparrows did end up in bush #1 at one point and there was some momentary flirtatious chasing like I had seen at Seminar II. At one point the sparrow that was at the feeders went into the ferns and then hopped backed out and rushed at a junco, which flew away. Then a towhee arrived and chased the sparrow out from under the feeders. The bird then headed over to a rhododendron bush and a pair of towhees followed.

Date: November 19 Part 2

Climate: 50°, overcast, slight wind (5 mph)

Latitude: 47°04’21.18” N

Longitude: 122°58’44.55” W

Observation time: 1:30 PM – 3:30 PM

After a lunch break, I returned to the area around the Seminar I bird feeders. A sparrow was foraging at the bottom of the yellow flowered bush #1, which is across the path from the feeders. Soon, another sparrow appeared and actually stood on top of and fed from the hanging caged feeder. The other sparrow hopped to the top of bush #1 and seemed to be looking over at the other bird feeding. He wing flipped, shook himself, and increasingly chirped before he flew over to the ferns next to the feeder. The other sparrow then joined him in the ferns and they both foraged along the ground in the ferns and below the feeders, wing flipping away. A few spotted towhees also joined the sparrows to forage.

Based on his behavior, the one I believe to be a male flew back over to the bushes and was upset over something. He constantly wing flipped and chirped for a bit and then flew over to the Long House garden. Of course, a towhee followed right after him. The other song sparrow (a female?) continued to feed along the ground underneath the feeders and ferns, splitting seeds with its bill and discarding the unwanted parts before eating it. After a while, the bird headed over to the adjacent bushes, hopped down to the bottom, and disappeared from view. Maybe she was resting?

To make sure the bird was still there after some time passed by, I played the song and call, which she did not call or sing back to but simply hopped out onto a lower branch of the bush and scanned around. There were no wing flips to be seen. Over in the longhouse garden, I found the male in the young fir tree, he or some other male had been in hours before. He was extremely upset by my presence and was body pooping, wing popping, chirping, and started darting around to different bushes and trees. I let him be soon after.

Date: December 2

Climate: 37°, sunny, some wind (5 to 10 mph)

Latitude: 47°04’21.18” N

Longitude: 122°58’44.55” W

Observation time: 12:20 PM – 3:20 PM

I found a song sparrow right away over in yellow flowered bush #1 at the Seminar I building by playing its song and call. The bird perched at the top of the bush, chirped a few times, and then hopped back down within the bush and out of sight. Two spotted towhees were also in the bush, and seemed to be more alert when the song sparrow was down at the bottom. The sparrow would often come back up to the top of the bush, wing/body flip, and look around when loud people walked by, some examples being loud steps (like heels, stomping, scuffing), talking (laughing or yelling), or dragging noisy objects (garbage can). The towhees eventually headed over to feeders, and the sparrow soon followed. As always, the sparrow flew over and landed inside the ferns, and then made its way over to the feeders via the ground under the ferns. After pecking for a few seconds under the feeders, it quickly dove back under the ferns. The sparrow soon started spending long periods of time under the ferns.

A pair of Steller’s jays arrived after a while and began to eat from the feeders. A few minutes later, a bald eagle circled overheard, and the jays started rattling of their scratchy calls, and some dark eyed juncos joined in the alarm calls. Seemingly in response to the other birds, the song sparrow came out from under the ferns and stood amongst some dead leaves, wing flipping and quietly chirping. I could hear another song sparrow over in the long house garden and it seemed pretty upset, constantly calling and I’m sure it was wing flipping too for quite an extended period of time. The other song sparrow remained on the ground outside the ferns, just scanning and turning its head from side to side for quite a while until it finally began to forage amongst the dead leaves, then under the feeders, then back under the ferns, and I never heard any movement so it is possible that the bird taking a break to preen or rest.

Another sparrow arrived on scene, possibly the one from the Long House and dove under the ferns. All was silent for a bit and one of the sparrows finally emerged from the ferns and headed over to a feeder that was hung from a window, where it foraged underneath it. The other sparrow flew up onto another feeder that was hung on a window and hung nearly upside down on it for a few seconds before it flew back down into the ferns to eat the seeds. One of the birds then headed over to yellow flowered bush #2 and perched about six feet off the ground in the paper birch tree, where it constantly chirped and slightly body popped for bit, then flew over to yellow flowered bush #1. It then hopped down and foraged in the dead leaves beside the bush and then possibly chased another song sparrow out of bush #2. The bird then headed back to bush #1 then to the rhododendron bush.

At 1:40, I headed over to the Seminar II feeder and fond a song sparrow in the snow berry bushes on the other side of the wall from the feeder. The bird soon hopped up and perched on a snow berry branch about five feet away from where I was standing and looked at me before it took off and I lost it. I headed down to the garden soon after to see if I could find another sparrow and played their song. As I played, I felt like I was being watched. I turned around and spotted a song sparrow perched on top of a tall, skinny tree stump. After I stopped the song, the bird sang back quietly a few times and then flew under a young pine tree, where he foraged amongst the wood chips, scratching with his feet and pecking. After a few minutes, he hopped up in an unidentified bush, and began to preen himself, first his breast, then belly and underwing. He also inched himself and stretched out his wings and legs. He then flew under some nearby huckleberry bushes.

I headed back to the feeder and found a song sparrow actually perched on the feeder. It then dropped down below the feeder into the snow berry bushes where it finished eating its seeds. The bird then flew over the wall and sat on a branch in the snow berry bushes for about ten minutes, while a second one foraged for seeds underneath the feeder. The other bird flew back below the feeder and back over the wall a few more times before it stayed perched for ten minutes in the snow berry bushes again, where it was joined by the second song sparrow. It wasn’t long before one of them decided to go back below the feeder to forage but this time, a towhee chased it up into up into the red alder tree that holds the feeder. The sparrow then took seeds from it and dropped down into the snow berry bushes to eat them. Another sparrow soon appeared near the feeder, but it was chased away by the other individual. It wasn’t long before one of the sparrows was back foraging below the feeder and through the dead leaves nearby.

Date: December 3

Climate: 43°, overcast, no wind

Latitude: 47°04’22.39” N

Longitude: 122°58’34.70” W

Observation time: 1:05 PM – 4:05 PM

I checked the yellow flowered bushes and feeders at Seminar I for song sparrows but had no luck so I headed over to the Long House garden. Still no song sparrow. As a last resort I played calls and could hear a song sparrow way off behind the Long House. It soon came over and brought three spotted towhees with it. It perched ten feet off the ground in a possible paper birch then eventually flew back to its original location.

I headed over to the Seminar II feeder area and found a sparrow over in the snow berry bushes below the feeder. It soon hopped up about four feet into a nearby paper birch tree and flew over the wall and into the snowberry bushes beyond it where another sparrow came into view and started flirting with the other, wings out and fluttering quickly, and bowing the probable male followed the other bird around. Shortly after, one of the birds disappeared while the other continued to hop around the snow berry bushes. It then flew over to the ground below the feeder and foraged in the dirt and dead leaves, scratching and pecking away. Two more sparrows appeared and headed to the snow berry bushes below the feeder. One eventually worked up the courage to grab some seeds from the feeder and bring them back down to the cover of the snow berry bushes and eat them.

The bird returned a few minutes later and actually fed from the feeder for an extended period of time. It did not leave to eat the seeds elsewhere but ate them while perched at the feeder. After ten minutes over the wall in the snow berry bushes over there, the bird was back on the feeder three more times and did not take the seeds to eat them elsewhere again. The brave feeder sparrow then flew to some ferns own the path while another hopped around in the snow berry bushes at the wall. That bird then flew over the wall and dove under snow berry bushes below the feeder and foraged in the dirt and dead leaves. Another individual joined the first and came out onto the path to forage, searching for and pecking in the cracks on the pavement.

A flurry of bird activity began with the arrival of juncos, chickadees, towhees, and nuthatches. One of the song sparrows responded by hopping about four feet off the ground in a snow berry bush, scanning around, and wing flipping. The bird then took off and started flirting with another sparrow that took off towards the ferns, and the other bird followed. Then all three song sparrows were back in the snow berry bushes next to the feeder. There was some flirting going on and a lot of wing flipping. The birds flew back and forth over the wall as the flirting continued. They then separated, as one fed for the feeder multiple times, another hopped around in the snow berry bushes the other side of the wall, and another foraged around on the ground beneath the feeder. The one at the wall stretched out its left wing while perched momentarily.

Awhile after, all three were back in the snow berry bushes at the feeder and more flirting took place. However, it wasn’t long before they separated again. One individual took to foraging to along the path again, while another was perched in the snow berry bushes next to the feeder. The second bird then fed from the feeder without leaving to eat the seeds elsewhere. Again, flirting took place in the snow berry bushes at the feeder and over the wall. They split up again, flew back and forth over the wall to forage below or at the feeder or hopped around the snow berry bushes, flirted again, and repeated the whole a few more times.

Date: December 7

Climate: 45°, foggy/overcast, no wind

Latitude: 47°04’22.39” N

Longitude: 122°58’34.70” W

Observation time: 12:00 PM – 4:00 PM

I went straight to the Seminar II feeder and immediately spotted a song sparrow perched atop the feeder. The bird stayed there for an extended period of time as it tried to reach a few sunflower seeds crumbs that were down at the bottom. The sparrow then dropped down to the ground below, where it continued to hop and run around under the snow berry bushes. A little while later, the bird climbed up a snow berry bush by hopping upward from branch to branch until it was at the top. It then scanned around and at the time there was a Steller’s jay calling off in the distance. It then flew back down to the ground below where it dug around in dead leaves and dirt. When song sparrows dig, they hop into the air just enough to get their feet off the ground and when they land, they pull both feet back. The hop is an incredibly quick motion and I had to watch it a few times to see just how the birds were digging. Digging can be noisy. It creates a rustling sound, as both dirt and leaves are thrown back behind the birds. Digging does not go without wing flipping at times.

After a while of uninterrupted foraging, a man talking loudly on his phone came walking up the path. The sparrow got high up into a snow berry bush and scanned around before it dropped back down under the bush to hide as the man passed. Soon after, the bird flew over the wall that stands across from the feeder and started to preen in the snow berry bushes. It preened its breast, underwings and back feathers first. It then worked on its tail feathers, first the right side, then left. It puffed up its entire body, then preened its throat feathers and shook its body. A few hundred feet away, another song sparrow made a high pitched chirp. My song sparrow matched the call with another high pitch chirp. The other bird matched the call in return. My song sparrow began to get upset and started body popping, then went back to preening but it was a more violent preening.

I soon spotted another song sparrow, who was silent, foraging along the ground under the snow berry bushes near the preening bird. It hopped past the other bird, who either did not notice or did not care and continued preening. The other bird flew up over the wall and down below the feeder. The other preening bird followed soon after and began perusing the other. No physical contact was made but there was a lot of chasing and it only lasted for a few minutes. One of the sparrows then took to foraging on the path for a few minutes, pecking at the cracks in the pavement. I then notice that there are actually three song sparrows. As they run around underneath the snow berry bushes near the feeder, I realize how humorous and speedy their running is. It is hard to tell if they run by quick hops or strides, but these birds are very fast on their feet when they want to be, though their body bounces around quite a bit.

One of the song sparrows gets upset and starts calling loudly before flying back over wall and hopping around in the snow berry bushes. Lots of junco’s, both types of chickadees, and a nuthatch had arrived at the feeder but left after a about minute or two. One song sparrow was still visible as it foraged in the dead leaves and dirt underneath the snow berry bushes. The other sparrow soon flew back over the wall and started foraging among the dead leaves and dirt too. Then more pursuing began but this time it lasted for quite a while. However, there was still no physical contact being made. One ran down the path wing flipping, then abruptly turned around and wing flipped some more before hopping under some ferns that are also below the feeder. Another took off and flew into a nearby fir tree. The two or three spotted towhees that had also been hanging around in the snow berry bushes started chasing each other around too.

The chasing continued, and the song sparrow that was chasing the other was wing flipping while it was chasing the other around. When not being chased, the other song sparrow would dig in the dead leaves and dirt. At one point, at least two of the song sparrows and spotted towhees were chasing each other around a fern bush, literally running around and around. It was pretty chaotic. Then the towhees went back under the snow berry bushes, and it was just two song sparrows at the fern bush. The sparrow that was being chased used the bush as a barrier and stayed on the opposite side that the other bird was on. If the chaser peaked around the corner of one side, the other sparrow would head to the opposite corner and stay out of view. The one being chased also hid behind the base of a snow berry bush where all the stems poked out and provided cover.

Eventually, one of the sparrows came back out of the bushes and pecked around on the path for a bit. It then stood motionless on the path and gazed up into the sky a few times before it headed back under the bushes. One of the sparrows then flew back over the wall and into the snow berry bushes, while the other continued to dig in the dead leaves and dirt under and around the feeder for a long time. The sparrow that had flown over the wall stayed there for about thirty minutes before it flew back over and foraged again around the feeder. One of the sparrows then rushed at a black-capped chickadee, which took off. Again, one of the sparrows flew back over the wall and dug amongst the rocks and snow berry bushes over there.

Back at the snow berry bushes at the feeder, one of the sparrows (maybe the chaser) started to sing quietly. He repeated his songs a few times, and there was much variation to the sound of the songs. He then climbed about three feet up into one of the snow berry bushes and continued to sing. I only recognized the ending to some of his songs, while others were more familiar. He sings about twenty songs in a row with spaces in between each song. After he finished his last song, he made two quiet chirps. He then sang about another twenty three songs, with another two quiet chirps at the end of his last song. The some new patterns: two more chirps, one song, two more chirps, one song, five to ten chirps, one song, five to ten chips, partial song, about five chirps, and two songs.

Another sparrow soon appeared and stood on the wall, made one high pitched chirp, and flew into the ferns near the feeder. The singer continued to sing a few more times, then made a few loud chirps before going silent for a bit. Both foraged amongst the dead leaves and dirt. Then, more quiet singing: fourteen songs in a row, one chirp, two more songs, one chirp, five songs, four chirps, three songs, two chirps, and six songs. The other sparrow did not react and continued to forage throughout the singing. The male then flew over the wall and sang twenty more songs in a row while he foraged below the snow berry bushes over there. Then sang about another twenty quiet songs, and even another batch of twenty. The other sparrow back at the feeder still did not react and kept feeding. The male sang another four songs, two chirps, one song, two chirps, one song, two chirps, one song, two chirps, and four more songs while he foraged. I could now see two song sparrows back at the feeder on the ground, digging and pecking on repeat. I could even hear one of them breaking seeds with its bill. They continued to forage for the rest of the encounter.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the Song Sparrow in the category of “Least Concern” and reports the population trends are stable (iucnredlist.org).

Habitat loss (particularly in riparian areas) is a concern for Song Sparrows (Larison et al. 2000). Due to the high diversity of plants and animals that these habitats maintain, conservationists have made restoring them a priority. However, the restored riparian habitats tend to offer fewer acceptable nest site as well as inferior protection from predators (Larison et al. 2000). Therefore, Song Sparrow populations tend to be less dense in the restored habitats in comparison to the mature habitats (Larison et al. 2001).

By DickDaniels (http://carolinabirds.org/) (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

The Song Sparrow also falls victim to the parasitic practices of the brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater). The female cowbird will lay her eggs in a Song Sparrow’s nest leaving her young to be raised by the Song Sparrow mother. Cowbirds are also one of the most frequent nest predators of the Song Sparrow. All this can greatly reduce the number of Song Sparrow fledglings produced (Rogers et al. 1997).

Some populations of Song Sparrows are also threatened by behavioral patterns of inbreeding (Reid et al 2007). Due to this inbreeding, the immune system’s ability to aid in defending against parasites is significantly lowered, leading to a lower survival rate among these populations (Reid et al 2007). This lowered immune response is present in all offspring that are the product of inbreeding, regardless of age (Reid et al. 2007).

Climate change is now a factor for song sparrows. However, it effects each life stage differently. Warmer, a drier winter increases survivability in adults, who are sensitive to cold temperatures, and for juveniles, a warmer, drier winter increases food availability the following summer (Dybala et al. 2013). Climate change, as well as El Nino years, also effect the timing of when song sparrows breed (Wilson et al. 2003).

-

- Song Sparrow near the Seminar II feeder at the Evergreen State College on December 3, 2014. Taken by Melisa Pinnow.

-

- Song Sparrow near the Seminar II feeder at the Evergreen State College on December 3, 2014. Taken by Melisa Pinnow.

-

- Song Sparrow near the Seminar II feeder at the Evergreen State College on December 3, 2014. Taken by Melisa Pinnow.

-

- Male Song Sparrow at the Long House garden at the Evergreen State College on November 19, 2014. Taken by Melisa Pinnow.

-

- Song Sparrow wing flips near the Seminar I feeder at the Evergreen State College on November 19, 2014. Taken by Melisa Pinnow.

-

- Song Sparrow near the Seminar I feeder at the Evergreen State College on November 19, 2014. Taken by Melisa Pinnow.

-

- Male Song Sparrow at the Long House garden at the Evergreen State College on November 9, 2014. Taken by Melisa Pinnow.

Akay, C., Searcy, W.A., Campbell, S., Reed, V.A., Templeton, C.N., Hardwick, K.M., & Beecher, M.D. (2012). Who initiates extrapair mating in song sparrows? Behavioral Ecology, 23(1): 44-45.

Akay, C., M. Tom, E. Campbell, and M. Beecher. 2013. Song type matching is an honest early threat signal in a hierarchical animal communication system. rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org, 280: 2-6.

Arcese, P. (1989). Intrasexual Competitioin and the Mating System in Primariously Monogamous Birds the Case of the Song Sparrow. Animal Behavior, 38(1): 96-111

Arcese, Peter, Mark K. Sogge, Amy B. Marr and Michael A. Patten. 2002. Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://0bna.birds.cornell.edu.cals.evergreen.edu/bna/species/704doi:10.2173/bna.704

Beecher, M.D., Campbell, S., & Nordby, J. (2000). Territory tenure in song sparrows is related to song sharing with neighbors, but not repertoire size. Animal Behavior, 59(1): 29-37.

BirdLife International 2012. Melospiza melodia. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. Retrieved From: www.iucnredlist.org

Burt, J., S. Campbell, and M. Beecher. (2001). Song type matching as threat: a test using interactive playback. Animal Behavior, 62(6): 6.

Chase, M. (2002). Nest Site Selection And Nest Site Success In Song Sparrow Population: The Significance Of Spatial Variation. Condor. 104(1).

Chase, M., N. Nur, and G. Geupel. (2005). Effects Of Weather And Population Density On Reproductive Success And Population Dynamics In A Song Sparrow (Melospiza Melodia) Population: A Long-Term Study. BioOne, 122(6): 588.

Dybala, K., J. Eadie, T. Gardali, N. Seavy, and M. Herzog. (2013). Projecting demographic responses to climate change: adult and juvenile survival respond differently to direct and indirect effects of weather in a passerine population. Global Change Biology, 19: 8.

Foote, J., Barber, C. (2007). High level of song sharing in an eastern population of song sparrow. The Auk, 124(1): 53-62.

Hatch, M.I. (1997). Variation in song sparrow nest defense: Individual consistency and relationship to nest success. Condor, 99(2): 282-289.

LaDeau, S., A. Kilpatrick, and P. Marra. (2007). West Nile virus emergence and large-scale declines of North American bird populations. Nature. 447.

Larison, B., Laymon, S.A., Williams, P.L., & Smith, T.B. (2001). Avian responses to restoration: Nest-site selection and reproductive success in Song Sparrows. Auk, 118(2): 432-442.

National Audubon Society (2010). The christmas bird count historical results [online]. Available http://christmasbirdcount.org [Jan 14, 2014].

Nice, M. (1943). Behavior of the Song Sparrow and other Passerines. The Birds of North America Online. [Online.] Retrieved at http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/704/articles/behavior.

Nordlund, C.A., & Barber, C.A. (2005). Parental provisioning in Melospiza melodia (Song Sparrows). Northeastern Naturalist, 12(4): 425-432.

Nowicki, S., W. Searcy, and M. Hughes. (1998). JSTOR: Behavior, 135(5): 615-628.

O’Loghlen, A., and M. Beecher. (1999). Mate, neighbor and stranger songs: a female song sparrow perspective. Animal Behavior. 58(1): 6-7.

Proctor, N.S. & Lynch, P.J. (1993). Manual of Ornithology: Avian Structure and Function. Yale University Press.

Pwrc.usgs.gov,. 2014. Bird Banding Laboratory. [Online.] Available at http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bbl/longevity/longevity_main.cfm.

Reed, J. (1981). Song Sparrow “Rules” for Feeding Nestlings. The Auk, 98(4): 831.

Reid, J.M., Arcese, P., Cassidy, A.V., Hiebert, S.M., Smith, J.M., Stoddard, P.K. &Keller, L.F. (2004). Song repertoire size predicts initial mating success in male song sparrows, Melospiza melodia. Animal Behavior, 68(5): 1055-1063.

Reid, J.M., Arcese, P., Keller, L., Elliot, K., Sampson, L., & Hasselquist, D. (2007). Inbreeding effects on immune response in free-living song sparrows (Melospiza melodia). Proceedings: Biological Sciences, 274(1610): 697-706.

Rogers, C.M., Taitt, M.J., Smith, J.M., & Jongejan, G. (1997). Nest predation and cowbird parasitism create a demographic sink in wetland-breeding song sparrows. Condor, 99(3): 622-633.

Sardell, R.J., Arcese, P., Keller, L.F., & Reid J.M. (2012). Are There Indirect Fitness Benefits of Female Extra-Pair Reproduction? Lifetime Reproductive Success or Within-Pair and Extra-Pair Offspring. American Naturalist, 179(6): 779-793.

Sibley, David Allen. (2003). Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Allfred A. Knopf Inc., NewYork.

Song Sparrow: Life History. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds. Retrieved From http//www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/song_sparrow/lifehistory

Stoddard, P., M. Beecher, C. Horning, and S. Campbell. (1991). Recognition of individual neighbors by song in the song sparrow, a species with song repertoires. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 29: 211-215.

Templeton, C., Akcay, C., Campbell, E., Beecher, M. (2010). Juvenile sparrows preferentially eavesdrop on adult song interactions. Proceedings: Biological Sciences, 277(1680): 447-453.

Templeton, C., S. Campbell, and M. Beecher. (2012). Territorial song sparrows tolerate juveniles during the early song-learning phase. Behavioral Ecology 23: 916-923.

Turner, W., Barber, C. (2004). Male song sparrows Melospiza melodia do not announce their female’s fertility. Journal of Avian Biology, 35(6): 483-486.

Wilson, S., Arcese, P. (2003). El Nino Drives Timing In Breeding But Not In Population Growth In The Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia). PNAS. 100(19).

Wood, W., Yezerinac, S. (2006). Song sparrow (Melospiza melodia) song varies with urban noise. The Auk, 123(3): 650-659.

Melisa Pinnow took Ornithology (taught by Alison Styring) in Fall Quarter of 2014 during her a sophomore year at The Evergreen State College. Despite having a majority of her experience centered around cetaceans, she found learning about the fascinating avian world very enjoyable, and has made birding one of her hobbies now.

Leave a Reply