Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

Genus: Cyanocitta

Species:Cyanocitta stelarri

Inroduction

Scientific Illustration of Steller’s Jay. Colored pencil and ink. Created by Jordan Marlor on 12/07/14.

The Steller ’s Jay is an easily recognizable medium to large songbird. The most distinguishable feature being its prominent triangular crest. It has a greyish black head, neck, breast, and back, with dark blue plumage elsewhere. It has a long tail and broad wings with narrow black barring on both. The bill is long, thick, and pointed, which is ideal for its foraging habits.

Adults have a blue supercilium or eyebrow, while the juveniles lack this distinguishing feature on their all black heads. It is difficult to differentiate which genderof jay you are looking at based off of plumage alone (Sibley 2003).

Steller’s Jays are common residents in coniferous and coniferous-deciduous forest and are well habituated to human environments where they inhabit neighborhoods, campgrounds, and parks. They will feed from bird feeders and have a reputation for stealing unattended food. The Steller’s Jay is a vociferous bird whose raucous call announces its presence often before it’s seen.

This jay is named after Georg Wilhelm Steller, a German botanist, zoologist, and explorer famous for his exploration of Alaska’s natural history during the 1740’s. Along with the jay, Stellar discovered five additional species of birds and mammals including the extant Steller ’s Sea Lion and Steller’s Eider (Greene et al. 1998).

There are 16 subspecies of Steller’s Jay currently recognized throughout their range from western North America to Central America (Greene et al. 1988). Notable variations in the subspecies include crest size (short- crested or long -crested) and crest color (black, gray, or blue).

Cyanocitta stellari stellari ranges from southern Alaska to northwest Oregon. It has a blackish to gray head, crest, and upper breast; a pale streaky throat; a deep blue overall plumage with an indigo tail; thin black barring on its wing and tail feathers. This subspecies varies in mass across its range, and individuals from the northern portion of its range tend to be larger compared to those seen in here Washington near the southern portion of its range (Greene et al. 1988).

- http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/21/Cyanocitta_stelleri_map.jpg/250px-Cyanocitta_stelleri_map.jpg

Steller’s Jays are generally resident or non-migratory birds (Morrison and Yoder-Williams 1984); however, populations whose breeding ranges are at high altitudes participate in short-distance migrations where they move to lower elevations for the winter. Birds that breed in the Cascade and Olympic mountains of Washington will migrate to lower elevations for the winter (Cassidy 2002). Occasionally irruptive migrations of young birds occur resulting in their appearance in habitats they don’t normally occupy (Green et al. 1988). Researchers Stewart and Shepard indicate a history of periodic invasions or rapid increase in the population of Steller’s Jays on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. They found that recent invasions included a significant proportion of adults; they theorize this suggests the irruptive migrations are related to food shortages not dispersal or wandering movements as often hypothesized (Stewart and Shepard 1994).

Steller’s Jays prefer to nest in trees (primarily coniferous), but they will nest on human structures in urban environments (Vigallon and Marzluff 2005a). While Steller’s Jays regularly nest in suburban and urban environments, fledgling success is highly reduced in these areas compared to those in forested areas with fragmented or edge structure. Reduced cover, human disturbance, and increased predator presence associated with urbanized environments contribute to a suboptimal habitat for the Steller’s Jay (Vigallon and Marzluff 2005a).

Steller’s Jays forage on the ground as well as in trees and bushes. They have excellent spatial memory, a trait common among Corvids, which allows them to successfully cache food by hiding it in trees, burying it under vegetation (Green et al. 1988), and scatter-hoarding seeds in the soil surface (Thayer and Vander Wall 2005). Their caches regularly consist of one or two seeds. Steller’s Jays will steal food from the caches of other birds (Burnell and Tomback 1985) and mammals (Thayer and Vander Wall 2005). Since Steller’s Jays rely on spatial memory not olfactory cues to locate caches, they’re more effective at robbing others when they observe the cache being made (Thayer and Vander Wall 2005). Some species have learned this attribute of the jays and will not cache food in the presence of a Steller’s Jay (Burnell and Tomback 1985, Thayer and Vander Wall 2005). Jays are able to hold large mast nuts such as acorns in their strong feet and use their bill to open and access the meat (Sibley 2001, Green et al. 1988).

Steller’s Jays can be observed on The Evergreen State College campus on the edges of forest and man-made landscapes (Latitude 47.02971, Longitude -122.978329). They can be observed carrying hazelnuts in their beaks during fall quarter. The City of Tumwater’s Pioneer Park (Latitude 46.996329, Longitude -122.885279) and Mima Mounds Natural Area Preserve (Latitude 46.904224, Longitude -123.047703), are additional places where Stellar’s Jays can be observed in fall where they can be seen flying with acorns in their bills (Perry per. obs.). Backyard habitats provide opportunities to observe jays; they can be observed foraging on sunflower seeds from gardens as well as feeders. In the fall, Steller’s Jay may be seen perched on a man-made structures (e.g. a roof apex) in order to use the structure to assist in opening mast nuts (e.g.hazelnut). The jay will hold the nut in its feet against the roof in order to stabilize the nut, and then pound it repetitively with its beak (Perry pers. obs). Jays can be observed flicking around leaf litter in search of food. They can be observed performing this ground foraging behavior in the fall at Pioneer Park under the landscaped oak trees searching for fallen acorns (Perry pers. obs.).

The calls of the Steller’s Jay can be heard on campus at The Evergreen State College. Steller’s Jays can be heard on the periphery of Red Square, in C parking lot, and in the vicinity of the Longhouse (Perry pers. obs.).

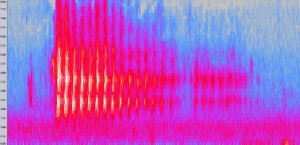

Spectrogram of Steller’s Jay call 1. Recorded at 0915 on 04 November 2012 by Kelly Perry at her backyard in east Olympia.

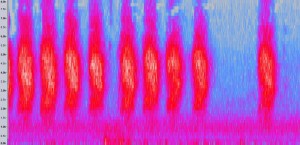

Spectrogram of Steller’s Jay call 2. Recorded at 1005 on 03 November 2012 by Kelly Perry at her backyard in east Olympia.

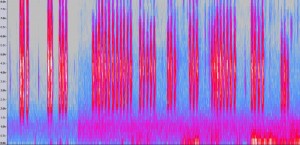

Spectrogram of Steller’s Jay call 3. Recorded at 1745 on 17 October 2012, by Kelly Perry at City of Olympia’s Mission Creek Nature Park (N47°03’23.5” W122°52’48.9”).

Spectrogram of Steller’s Jay call 4. Recorded at 1755 on 17 October by Kelly Perry at City of Olympia’s Mission Creek Nature Park (N47°03’23.5” W122°52’48.9”).

Steller’s Jay Call #1. Recorded at San Francisco St NE, Olympia on 11/24/2014. 47.056941, -122.882467

Steller’s Jay call #2. Recorded in the backyard of Jordan Marlor on 11/25/2014. 47.055033, -122.885096

The flight pattern of the Steller’s Jay is steady with downward glides (Sibley 2003). Steller’s Jays can also be spotted hopping along the ground as well as spiraling up trees from limb to limb usually close to the trunk (Green et al. 1988).

Social:

Mobbing is the act of several birds joining forces in attempt to encourage a threat to depart the area. Mobbing antics include chasing, dive-bombing, and surrounding the threat; these actions are paired with intense vocalizations. Mobbing will sometimes consist of mixed species flocks and is employed as an anti-predator response. Group mobs will incorporate the use of “wah” calls to produce a loud ruckus to help drive of threats (Sibley 2001).

M. Ficken reports spotting a Cooper’s Hawk’s (Accipiter cooperii) fall to the ground after being struck by a single Steller’s Jay in a mobbing event carried out by 5-6 jays. The Steller’s Jays were mobbing the hawk by flying close to its back and head while producing what she refers to as a chorus of “Wahs”. The hawk departed the area (Ficken 1989).

Steller’s Jays are social birds that pair their vocal repertoire with a variety of movements and postures including crest displays (Brown 1963a, Brown 1963b) to communicate their intentions. Their crests are generally depressed or flattened when they are resting, foraging, preening, and even during courtship. A reduced crest signals submission between rivals. The crest becomes erect during high-stress events that require more aggressive behavior, including alarming events such as mobbing and territorial defense in general. A raised crest is suggestive of willingness to attack rather than submit or flee during encounters with rivals (Brown 1963).

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/

thumb/8/89/Steller%27s_Jay_holding_

a_peanut.jpg

Intelligence:

Research on corvids investigating their cognitive ability demonstrates that not only do they have superior intelligence compared to most other birds (parrots are the known exception), their intelligence rivals that of non-human primates (Emory and Clayton 2004). Although the majority of this research used American Crows (Corvus brachyrhyncos) and Common Ravens (Corvus corax) as their study subjects, Steller’s Jays have demonstrated advanced cognitive skills. An example being their use of tools. Steller’s Jays were observed manufacturing a twig to be used in a spear like fashion to lunge at an American Crow when it refused to depart a feeding platform after unsuccessful lunging attempts without the twig (Balda 2007).

Nesting:

Steller’s Jays form long-term, year-round, monogamous pair bonds (BirdWeb). Both male and female Steller’s Jays choose their nest site and participate in the collection of construction materials. Stems, leaves, moss, and twigs are mortared together with mud to form a bulky nest cup ranging from 10 – 17 inches in diameter and about 6-7 inches in height (Greene et al 1998). The interior cup (2.5-3.5 inches deep) is lined with softer materials like pine needles, rootlets, and hair. They brood once a year with a clutch size ranging from 2-6 eggs. The incubation period and nestling period are 16 days (Greene et al 1998). Both members of the pair feed the young and will to provide some food to their young for approximately 30 days after they have fledged (BirdWeb).

Socially monogamous pairs of Steller’s Jays defend areas close to their nests and reduce defense efforts the further they venture from their nesting area or territorial center. The resulting effect is extensive overlapping of conspecific home ranges with unclear boundaries (Brown 1963). Research conducted in the redwood forests of northern California found that age had a consistent – although slight – influence on annual reproductive success for both male and female Steller’s Jays. The research also indicated that male jays who took fewer risks (e.g. were less exploratory) produced more offspring (Gabriel and Black 2012).

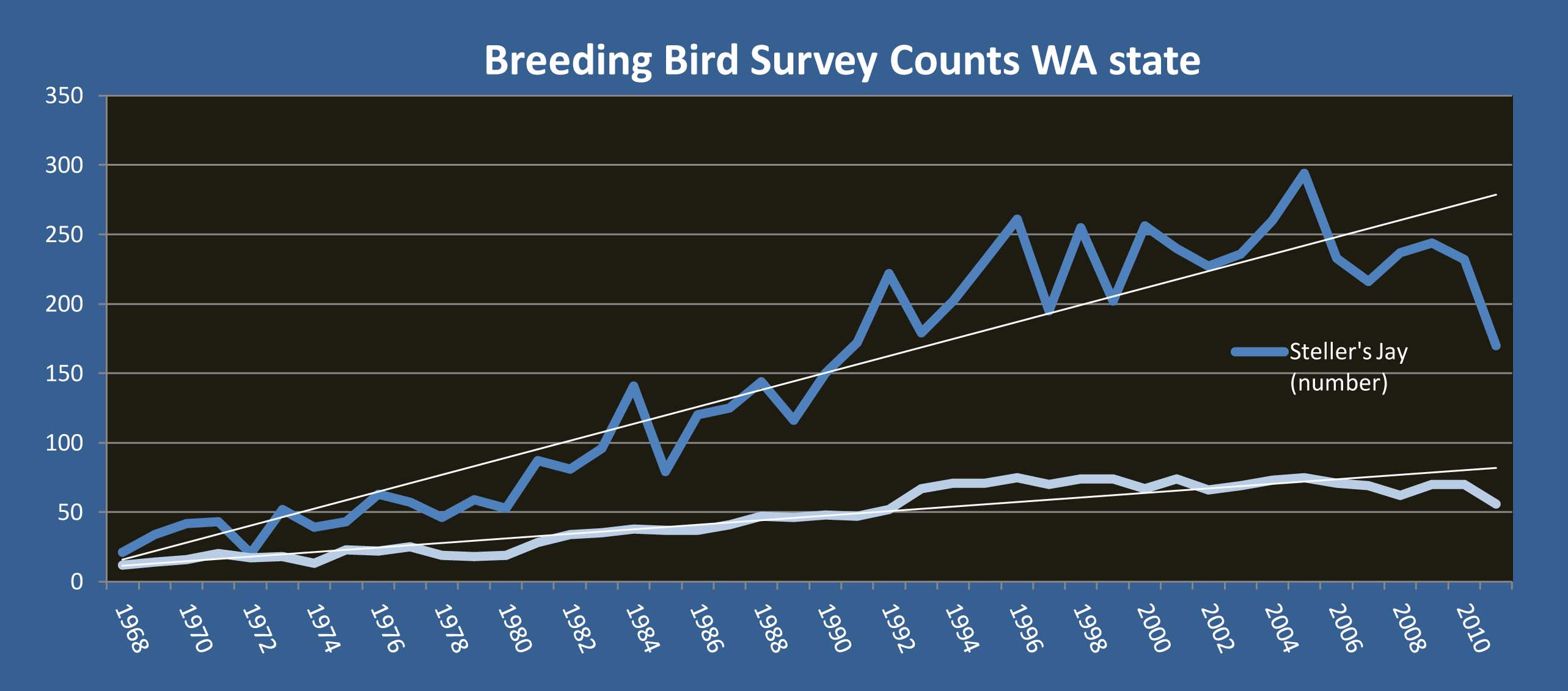

Graph data collected from Breeding Bird Survey raw data: U.S. Geological Survey

Department of the Interior/USGS, http://www.usgs.gov

Steller’s Jays have been increasing in abundance in Washington State based on annual North American Breeding Bird Survey counts conducted through the United States Geographical Survey. An increase in jay numbers can be partially attributed to increased survey efforts; ergo, the trend-line for number of jays observed is steeper than the trend-line for survey effort suggesting an increase in Steller’s Jay abundance. The population declined since 2009 after peaking in 2005; it will be interesting to see what happens over the next few years.

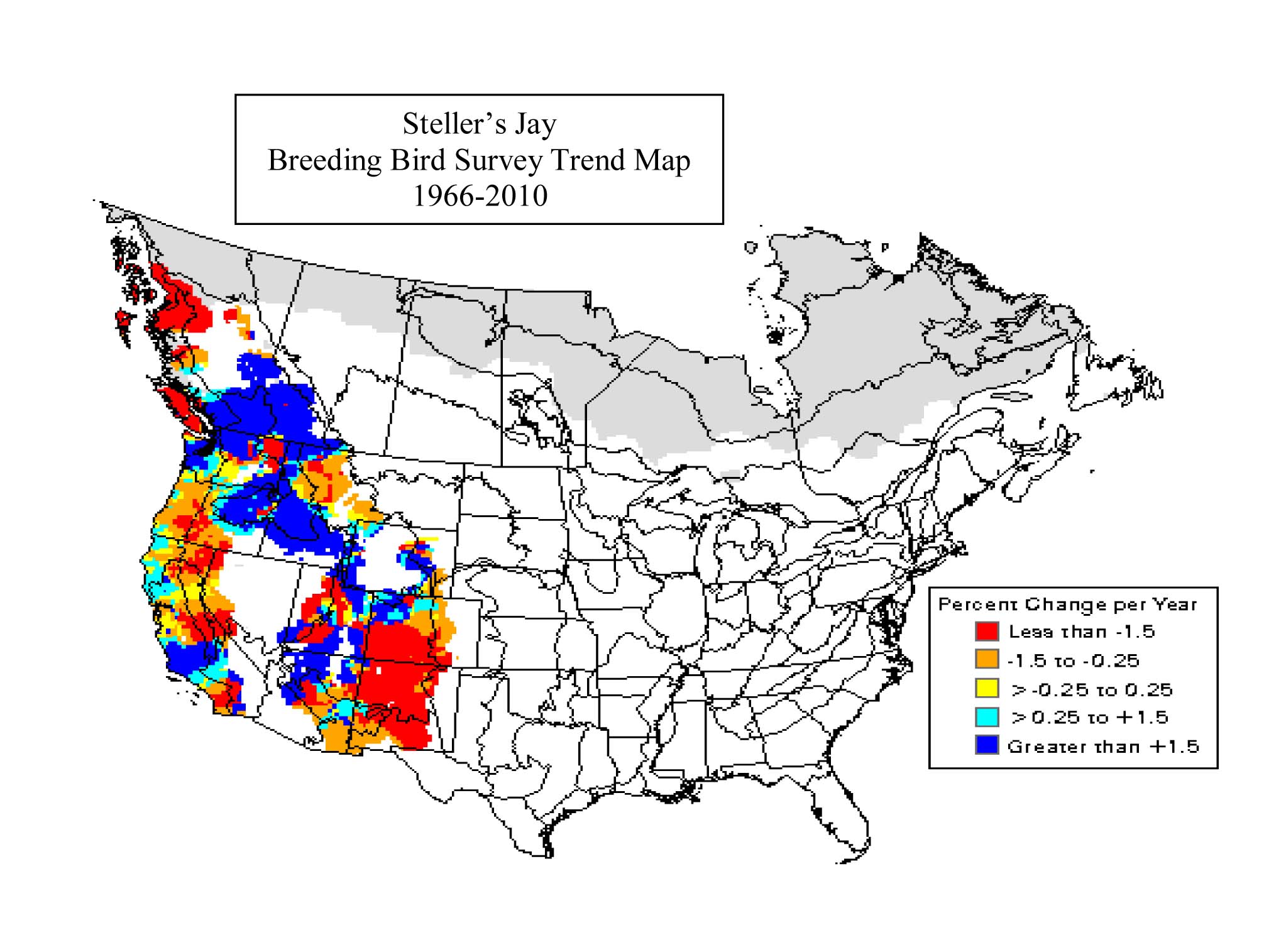

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey, Department of the Interior, http://www.usgs.govSurvey

Results indicate an increasing population trend for much of the Steller’s Jays range including the Pacific Northwest. The largest declines are primarily at the southeast and northern edge of their range.

Although not a species of concern themselves, Steller’s Jays negatively impact other bird species such as the Marbled Murrelet, (Brachyramphus marmoratus), listed under the Endangered Species Act as a threatened species in Washington, Oregon, and California (Raphael et al. 2001). Fragmented habitat and forest edges are preferred by Steller’s Jay, (Marzluff and Millspaugh 2004), this preference, paired with the increasing quantity of fragmented forests and an escalating rarity of contiguous old-growth forests (Roberts et al. 2005), has lead to an increase in nest predation by Steller’s Jay on the Marbled Murrelet (Hebert and Golightly 2007, Vigallon and Marzluff 2005b).

While they were more abundant in this area, trying to conduct field research in residential areas proved to be problematic. For some reason, people seem to be wary of a person wearing large binoculars asking to look in their backyard at a bird. This meant a majority of the research time was spent tracking the birds through residential areas compared to strictly observing the birds behavior.

Below is a graph representing the specific data collected pertaining to the foraging behaviors of the Steller’s Jay. From this information and from my observations, I was able to generalize that the Steller’s Jay was predominantly found in the high reaches of tall conifers but a majority of the its foraging behaviors occurred on smaller trees and on the ground. They consumed and cached a wide variety of types of food, and were opportunistic of other birds food stores. Most interestingly to the researcher, he observed with each specimen a definite ability to be selective in what they chose to take which implies a high level of reasoning skills for a bird.

Birds of Evergreen Terrestrial Species Foraging Spreadsheet (Steller’s Jay)

BirdWeb. Seattle Audubon Society. http://www.birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/stellers_jay

Brown, J. L. 1963a. Aggressiveness, dominance and social organization in the Steller Jay. Condor 65:460-484.

Brown, J. L. 1963b. Ecogeographic variation and introgression in an avian visual signal the crest of the Steller’s Jay, Cyanocitta stelleri. Evolution 17:23-39.

Burnell, K.L. and D.F. Tomback. 1985. Steller’s Jays steal Gray Jay caches in field and laboratory observations. Auk 102:417-419.

Carothers, S.W., N.J. Sharber, and R.P. Balda. 1972. Steller’s Jay prey on Gray-headed Juncos and a Pygmy Nuthatch during periods of heavy snow. The Wilson Bulletin. 84:204-205.

Cassidy, K. 2012. Washington range map for Steller’s Jay. BirdWeb. The Seattle Audubon Society. http://www.birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/stellers_jay

Emory, N.J., and N.S. Clayton. 2004. The mentality of crows: convergent evolution of intelligence in corvids and apes. Science. 306:1903-1907.

Flicken, M.S. 1989. Are mobbing calls of Steller’s Jays a “confusion chorus”? Journal of Field Ornithology. 60:52-55.

Gabriel, P.O. and J.M. Black. 2012. Reproduction in Steller’s Jays (Cyanocitta stelleri): Individual characteristics and behavioral strategies. The Auk. 129:377-386.

Greene, Erick, William Davison and Vincent R. Muehter. 1998. Steller’s Jay (Cyanocitta stelleri), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://0- bna.birds.cornell.edu.cals.evergreen.edu/bna/species/343doi:10.2173/bna.343

Herbert P.N. and R.T. Golightly. 2007. Observation of predation by corvids at a Marbled Murrelet nest. Journal of Field Ornithology. 78:221-224.

Hope, S. 1980. Call form in relation to function in the Steller’s Jay. The American Naturalist 116:788-820.

International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 07 November 2012. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/106005687/0

Luginbuhl, J.M., J.M. Marzluff, J.E. Bradley, M.G. Raphael, and D.E. Varland. 2001. Corvid survey techniques and the relationship between corvid relative abundance and nest predation. Journal of Field Ornithology 72, 556–572.

Marlor, W. 2014. Unpublished field journal. Ornithology. Fall 214. Allison Styring faculty.

Marzluff, J.M., J.J. Millspaugh, P. Hurvitz, and M.S. Handcock. 2004. Relating resources to a probabilistic measure of space use: forest fragments and Steller’s Jays. Ecology 85:1411–1427.

Marzluff, J.M., and E. Neatherlin. 2006. Corvid response to human settlements and campgrounds: Causes, consequences, and challenges for conservation. Biological Conservation 130: 301-314.

Morrison, M. L. and M. P. Yoder-Williams. 1984. Movements of Steller’s Jays in western North America. North American Bird Bander 9:12-15.

Perry, K. 2012. Unpublished nature journal. Ornithology. Fall 2012. Alisson Styring and Dina Roberts faculty. Pp. 6-89.

Raphael, M. G., J. Baldwin, G.A. Falxa, M.H. Huff, M. Lance, S.L. Miller, S. F. Pearson, C.J. Ralph,; C. Strong, C. Thompson. 2007. Regional population monitoring of the marbled murrelet: field and analytical methods. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-716. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 70 p. http://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/00118/

Roberts, L., G. Falxa, R.Brown, B. Tuerler, and J. D’Elia. 2009. Final 2009 5-year review for the Marbled Murrelet. U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife Service. Lacey WA.

Sibley, DA. 2001. Crows and jays in the Sibley guide to bird life and behavior. pp 408-415. C. Elphick, J.B. Dunning Jr., D.A. Sibley. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. New York.

Sibley, DA. 2003. The Sibley field guide to birds of western North America. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. New York.

Sieving K.E. and M.F. Wilson. 1999. A temporal shift in Steller’s Jay predation on bird eggs. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 77:1829-1834.

Stewart, A. C. and M. G. Shepard. 1994. Steller’s Jay invasion of Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. North American Bird Bander 19:90-95.

Thayer, T. C. and Vander Wall, S. B. (2005), Interactions between Steller’s jays and yellow pine chipmunks over scatter-hoarded sugar pine seeds. Journal of Animal Ecology, 74: 365–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00932.x

Vigallon, S.M., and J.M. Marzluff. 2005a. Abundance, nest sites, and nesting success of Steller’s Jay along a gradient of urbanization in Western Washington. Northwest Science 79:22-27.

Vigallon S. M. and J.M. Marzluff. 2005b. Is nest predation by Steller’s Jays (Cyanocitta stelleri) incidental or the Result of a specialized search strategy? The Auk 122:36-49.

Leave a Reply