Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

Latin Name: Melanitta deglandi

The White Winged Scoter is the largest Scoter in Washington (DOFAW, 2015)

They are 21 inches in length and are one of the largest ducks in the world. The females are dark brown and the males are black. Both the male and female have red legs and a white stripe on the top side of their wings. (PBS, n.d.)

The oldest recorded White Winged Scoter is a female who is at least 18 years old. (All About Birds, n.d.)

Migration patterns for the White Winged Scoter involve a trip from the Puget Sound Area to Alaska in the spring. They stick to the routes they take and rarely change them. (De La Cruz, 2009)

White Winged Scoters in Washington spend the winter in the Salish Sea area. White Winged Scoters also change habitat during breeding season. They move from salt water areas in the spring to inland areas like the boreal forests in Alberta and other areas in the northwest.(DOFAW, 2015) During the summer their breeding grounds include Alaska and Canada. They also prefer coastlines, freshwater lakes, rivers the wooded arctic tundra and alpine zones during this season. (PBS, n.d.)

The White Winged Scoter dives for its food. They eat mostly clams, mussels and mollusks however they will also eat small fish, amphipods, isopods and echinoderms. When they live in fresh water environments they will eat plant material and insects.(PBS, n.d.) Density and availability of clams in a habitat has a minor effect of the White Winged Scoters foraging behavior in healthy habitats. (Lewis, 2008) Adult males with the average body mass in a population has the highest survival chances through the winter (Uher-Koch, 2016) As bivalve populations decline so do Scoter populations in areas like the Chesapeake Bay. (Wells-Berlin, 2015) Surf Scoters a close relative to White Winged Scoters will eat sand in order to use it to grind food up in their gizzard. (Evens, 2017)

There are differences between Atlantic and Pacific White Winged Scoters. Pacific White Winged Scoters initiate nest creation at an earlier date.(Gurney, 2014) Surf Scoters a close relative to White Winged Scoters will travel about 4,000 meters from foraging areas to places further out from shore during nocturnal hours making them more vulnerable to shipping traffic. (Hamilton, 2015) During nocturnal hours White Winged Scoters also dove for there food much less. They spent 0.1 minutes underwater per half hour observation as apposed to during the day where they spent 7 minutes underwater per half hour observation. (Lewis, 2015) Regardless of breeding origin the migration routes of White Winged Scoters remains the same. (Meattey, 2018) Flock sizes of Scoters increased as bald eagle populations increased in the habitat of the Scoters. (Middleton, 2018)

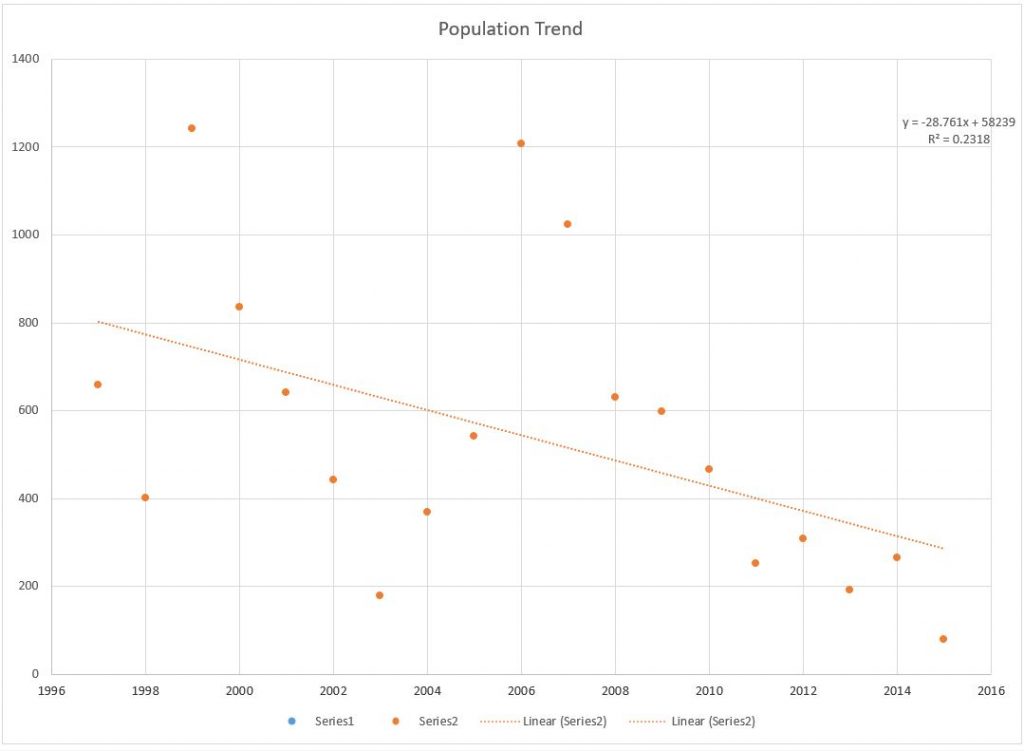

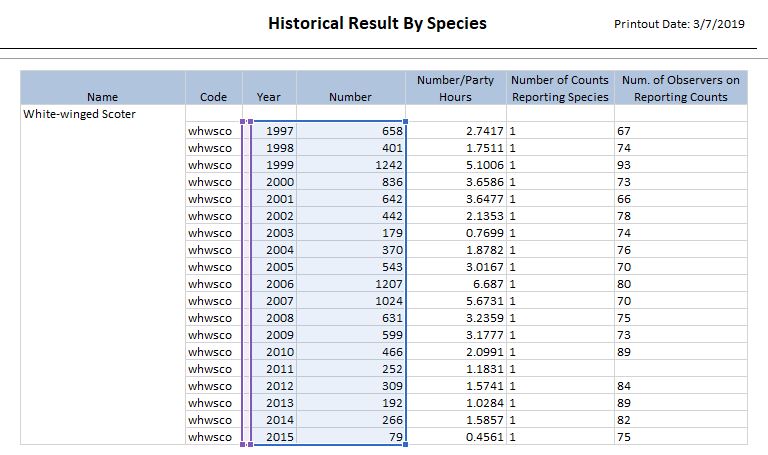

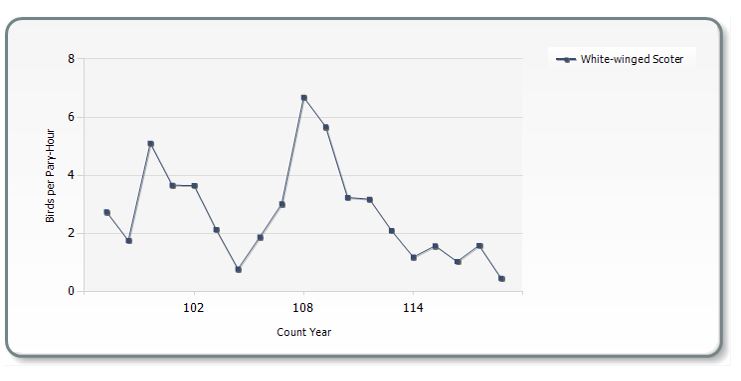

The White Winged Scoter breeds at two to three years old. (DOFAW, 2015) Female Scoters in the Pacific have lover concentrations of Cd, Pb and Se than Atlantic Scoters (Gurney, 2014) In the Puget Sound area populations of White Winged Scoters have been declining. 50% since around 1995 and possible 78% since around 1978-1979 This is likely do to real estate development and pollution in the area. In addition reduction of herring spawn is likely a factor in their decline. In the winter populations of all Scoters in the Puget Sounds reaches approximatley 50,000 20% of which are White Winged Scoters. (DOFAW, 2015) Destruction to stopover sites for migrating birds has a major impact on their populations. (Studds, 2017)

Papers 2009-2014 De La Cruz, S., Takekawa, J., Wilson, M., Nysewander, D., Evenson, J., Esler, D., . . . Ward, D. (2009). Spring migration routes and chronology of surf scoters (Melanitta perspicillata): A synthesis of Pacific coast studies. Retrieved February 26, 2019, from http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/Z09-099#.XHYEvYhKiUk Dickson, R. (2011). POSTBREEDING ECOLOGY OF WHITE-WINGED SCOTERS (MELANITTA FUSCA) AND SURF SCOTERS (M. PERSPICILLATA) IN WESTERN NORTH AMERICA: WING MOULT PHENOLOGY, BODY MASS DYNAMICS AND FORAGING BEHAVIOUR. Retrieved February 26, 2019, from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/56376153.pdf 2014-2019 Gurney, B., K. E., J., C., Alisauskas, T., R., Mark, . . . M., S. (2014, April 23). Identifying carry-over effects of wintering area on reproductive parameters in White-winged Scoters: An isotopic approach. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/condor/article/116/2/251/5153099?searchresult=1#130374541 Uher‐Koch, B. D., Esler, D., Dickson, R. D., Hupp, J. W., Evenson, J. R., Anderson, E. M., . . . Schmutz, J. A. (2014, August 27). Survival of surf scoters and white‐winged scoters during remigial molt. Retrieved February 26, 2019, from https://wildlife.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jwmg.774 Hamilton, L. (2015, September). NOCTURNAL HABITAT SELECTION OF WINTERING SURF SCOTERS IN THE SALISH SEA. Retrieved from http://archives.evergreen.edu/masterstheses/Accession86-10MES/Hamilton_LMESThesis2015.pdf Lewis, T. L., Esler, D., Boyd, W. S., & Ydelis, R. (2015). Nocturnal Foraging Behavior Of Wintering Surf Scoters And White-Winged Scoters. The Condor, 107(3), 637. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2005)107[0637:nfbows]2.0.co;2 Wells-Berlin, A. M., Perry, M. C., Kohn, R. A., Paynter, K. T., & Ottinger, M. A. (2015). Composition, Shell Strength, and Metabolizable Energy of Mulinia lateralis and Ischadium recurvum as Food for Wintering Surf Scoters (Melanitta perspicillata). Plos One, 10(5). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119839 Uher-Koch, B. D., Esler, D., Iverson, S. A., Ward, D. H., Boyd, W. S., Kirk, M., . . . Schmutz, J. A. (2016). Interacting effects of latitude, mass, age, and sex on winter survival of Surf Scoters (Melanitta perspicillata): Implications for differential migration. Canadian Journal of Zoology,94(3), 233-241. doi:10.1139/cjz-2015-0107 Evens, J., & Nordbye, T. (2017). Unusual Foraging Behavior By Surf Scoters (Melanitta perspicillata) In the Swash Zone. Northwestern Naturalist, 98(3), 241-242. doi:10.1898/nwn17-01.1 Studds, C. E., Kendall, B. E., Murray, N. J., Wilson, H. B., Rogers, D. I., Clemens, R. S., . . . Fuller, R. A. (2017). Rapid population decline in migratory shorebirds relying on Yellow Sea tidal mudflats as stopover sites. Nature Communications, 8, 14895. doi:10.1038/ncomms14895 Meattey, D., Mcwilliams, S., Paton, P., Lepage, C., Gilliland, S., Savoy, L., . . . Osenkowski, J. (2018). Annual cycle of White-winged Scoters (Melanitta fusca) in eastern North America: Migratory phenology, population delineation, and connectivity. Canadian Journal of Zoology,96(12), 1353-1365. doi:10.1139/cjz-2018-0121 Middleton, H. A., Butler, R. W., & Davidson, P. (2018). Waterbirds Alter their Distribution and Behavior in the Presence of Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). Northwestern Naturalist,99(1), 21-30. doi:10.1898/nwn16-21.1 Databases/ Not Papers Washington Department Of Fish And Wildlife. (2015). Species of Greatest Conservation Need Fact Sheets. Retrieved from https://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/01742/11_A2_Birds.pdf PBS. (n.d.). White-winged Scoter – Melanitta deglandi | Wildlife Journal Junior – Wildlife Journal Junior. Retrieved from https://nhpbs.org/wild/whitewingedscoter.asp White-winged Scoter Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/White-winged_Scoter/overview

Leave a Reply